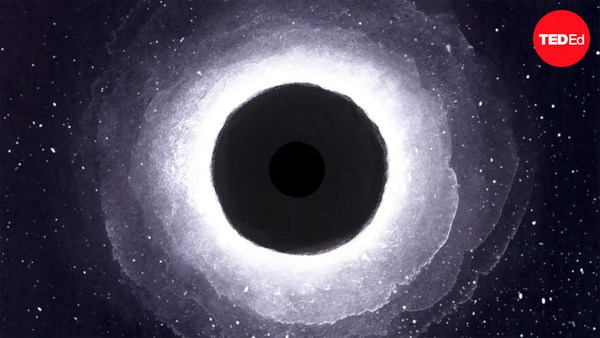

Black holes are among the most destructive objects in the universe. Anything that gets too close to the central singularity of a black hole, be it an asteroid, planet, or star, risks being torn apart by its extreme gravitational field. And if the approaching object happens to cross the black hole’s event horizon, it’ll disappear and never re-emerge, adding to the black hole’s mass and expanding its radius in the process. There is nothing we could throw at a black hole that would do the least bit of damage to it. Even another black hole won’t destroy it– the two will simply merge into a larger black hole, releasing a bit of energy as gravitational waves in the process. By some accounts, it’s possible that the universe may eventually consist entirely of black holes in a very distant future. And yet, there may be a way to destroy, or “evaporate,” these objects after all. If the theory is true, all we need to do is to wait.

In 1974, Stephen Hawking theorized a process that could lead a black hole to gradually lose mass. Hawking radiation, as it came to be known, is based on a well-established phenomenon called quantum fluctuations of the vacuum. According to quantum mechanics, a given point in spacetime fluctuates between multiple possible energy states. These fluctuations are driven by the continuous creation and destruction of virtual particle pairs, which consist of a particle and its oppositely charged antiparticle.

Normally, the two collide and annihilate each other shortly after appearing, preserving the total energy. But what happens when they appear just at the edge of a black hole’s event horizon? If they’re positioned just right, one of the particles could escape the black hole’s pull while its counterpart falls in. It would then annihilate another oppositely charged particle within the event horizon of the black hole, reducing the black hole’s mass. Meanwhile, to an outside observer, it would look like the black hole had emitted the escaped particle.

Thus, unless a black hole continues to absorb additional matter and energy, it’ll evaporate particle by particle, at an excruciatingly slow rate. How slow? A branch of physics, called black hole thermodynamics, gives us an answer.

When everyday objects or celestial bodies release energy to their environment, we perceive that as heat, and can use their energy emission to measure their temperature. Black hole thermodynamics suggests that we can similarly define the “temperature” of a black hole. It theorizes that the more massive the black hole, the lower its temperature. The universe’s largest black holes would give off temperatures of the order of 10 to the -17th power Kelvin, very close to absolute zero. Meanwhile, one with the mass of the asteroid Vesta would have a temperature close to 200 degrees Celsius, thus releasing a lot of energy in the form of Hawking Radiation to the cold outside environment. The smaller the black hole, the hotter it seems to be burning– and the sooner it’ll burn out completely.

Just how soon? Well, don’t hold your breath. First of all, most black holes accrete, or absorb matter and energy, more quickly than they emit Hawking radiation. But even if a black hole with the mass of our Sun stopped accreting, it would take 10 to the 67th power years– many many magnitudes longer than the current age of the Universe— to fully evaporate. When a black hole reaches about 230 metric tons, it’ll have only one more second to live. In that final second, its event horizon becomes increasingly tiny, until finally releasing all of its energy back into the universe. And while Hawking radiation has never been directly observed, some scientists believe that certain gamma ray flashes detected in the sky are actually traces of the last moments of small, primordial black holes formed at the dawn of time.

Eventually, in an almost inconceivably distant future, the universe may be left as a cold and dark place. But if Stephen Hawking was right, before that happens, the normally terrifying and otherwise impervious black holes will end their existence in a final blaze of glory.