You've all been in a bar, right?

(Laughter)

But have you ever gone to a bar and come out with a $200 million business? That's what happened to us about 10 years ago. We'd had a terrible day. We had this huge client that was killing us. We're a software consulting firm, and we couldn't find a very specific programming skill to help this client deploy a cutting-edge cloud system. We have a bunch of engineers, but none of them could please this client. And we were about to be fired.

So we go out to the bar, and we're hanging out with our bartender friend Jeff, and he's doing what all good bartenders do: he's commiserating with us, making us feel better, relating to our pain, saying, "Hey, these guys are overblowing it. Don't worry about it." And finally, he deadpans us and says, "Why don't you send me in there? I can figure it out." So the next morning, we're hanging out in our team meeting, and we're all a little hazy ...

(Laughter)

and I half-jokingly throw it out there. I say, "Hey, I mean, we're about to be fired." So I say, "Why don't we send in Jeff, the bartender?"

(Laughter)

And there's some silence, some quizzical looks. Finally, my chief of staff says, "That is a great idea."

(Laughter)

"Jeff is wicked smart. He's brilliant. He'll figure it out. Let's send him in there."

Now, Jeff was not a programmer. In fact, he had dropped out of Penn as a philosophy major. But he was brilliant, and he could go deep on topics, and we were about to be fired. So we sent him in. After a couple days of suspense, Jeff was still there. They hadn't sent him home. I couldn't believe it. What was he doing?

Here's what I learned. He had completely disarmed their fixation on the programming skill. And he had changed the conversation, even changing what we were building. The conversation was now about what we were going to build and why. And yes, Jeff figured out how to program the solution, and the client became one of our best references.

Back then, we were 200 people, and half of our company was made up of computer science majors or engineers, but our experience with Jeff left us wondering: Could we repeat this through our business? So we changed the way we recruited and trained. And while we still sought after computer engineers and computer science majors, we sprinkled in artists, musicians, writers ... and Jeff's story started to multiply itself throughout our company. Our chief technology officer is an English major, and he was a bike messenger in Manhattan. And today, we're a thousand people, yet still less than a hundred have degrees in computer science or engineering. And yes, we're still a computer consulting firm. We're the number one player in our market. We work with the fastest-growing software package to ever reach 10 billion dollars in annual sales. So it's working.

Meanwhile, the push for STEM-based education in this country -- science, technology, engineering, mathematics -- is fierce. It's in all of our faces. And this is a colossal mistake. Since 2009, STEM majors in the United States have increased by 43 percent, while the humanities have stayed flat. Our past president dedicated over a billion dollars towards STEM education at the expense of other subjects, and our current president recently redirected 200 million dollars of Department of Education funding into computer science. And CEOs are continually complaining about an engineering-starved workforce. These campaigns, coupled with the undeniable success of the tech economy -- I mean, let's face it, seven out of the 10 most valuable companies in the world by market cap are technology firms -- these things create an assumption that the path of our future workforce will be dominated by STEM.

I get it. On paper, it makes sense. It's tempting. But it's totally overblown. It's like, the entire soccer team chases the ball into the corner, because that's where the ball is. We shouldn't overvalue STEM. We shouldn't value the sciences any more than we value the humanities. And there are a couple of reasons.

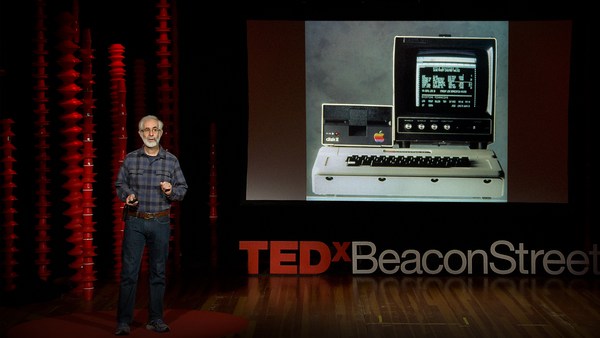

Number one, today's technologies are incredibly intuitive. The reason we've been able to recruit from all disciplines and swivel into specialized skills is because modern systems can be manipulated without writing code. They're like LEGO: easy to put together, easy to learn, even easy to program, given the vast amounts of information that are available for learning. Yes, our workforce needs specialized skill, but that skill requires a far less rigorous and formalized education than it did in the past.

Number two, the skills that are imperative and differentiated in a world with intuitive technology are the skills that help us to work together as humans, where the hard work is envisioning the end product and its usefulness, which requires real-world experience and judgment and historical context. What Jeff's story taught us is that the customer was focused on the wrong thing. It's the classic case: the technologist struggling to communicate with the business and the end user, and the business failing to articulate their needs. I see it every day. We are scratching the surface in our ability as humans to communicate and invent together, and while the sciences teach us how to build things, it's the humanities that teach us what to build and why to build them. And they're equally as important, and they're just as hard.

It irks me ... when I hear people treat the humanities as a lesser path, as the easier path. Come on! The humanities give us the context of our world. They teach us how to think critically. They are purposely unstructured, while the sciences are purposely structured. They teach us to persuade, they give us our language, which we use to convert our emotions to thought and action. And they need to be on equal footing with the sciences. And yes, you can hire a bunch of artists and build a tech company and have an incredible outcome.

Now, I'm not here today to tell you that STEM's bad. I'm not here today to tell you that girls shouldn't code.

(Laughter)

Please. And that next bridge I drive over or that next elevator we all jump into -- let's make sure there's an engineer behind it.

(Laughter)

But to fall into this paranoia that our future jobs will be dominated by STEM, that's just folly. If you have friends or kids or relatives or grandchildren or nieces or nephews ... encourage them to be whatever they want to be.

(Applause)

The jobs will be there. Those tech CEOs that are clamoring for STEM grads, you know what they're hiring for? Google, Apple, Facebook. Sixty-five percent of their open job opportunities are non-technical: marketers, designers, project managers, program managers, product managers, lawyers, HR specialists, trainers, coaches, sellers, buyers, on and on. These are the jobs they're hiring for. And if there's one thing that our future workforce needs -- and I think we can all agree on this -- it's diversity. But that diversity shouldn't end with gender or race. We need a diversity of backgrounds and skills, with introverts and extroverts and leaders and followers. That is our future workforce. And the fact that the technology is getting easier and more accessible frees that workforce up to study whatever they damn well please.

Thank you.

(Applause)