We've all heard about how the dinosaurs died. The story I'm going to tell you happened over 200 million years before the dinosaurs went extinct. This story starts at the very beginning, when dinosaurs were just getting their start. One of the biggest mysteries in evolutionary biology is why dinosaurs were so successful. What led to their global dominance for so many years? When people think about why dinosaurs were so amazing, they usually think about the biggest or the smallest dinosaur, or who was the fastest, or who had the most feathers, the most ridiculous armor, spikes or teeth. But perhaps the answer had to do with their internal anatomy -- a secret weapon, so to speak. My colleagues and I, we think it was their lungs.

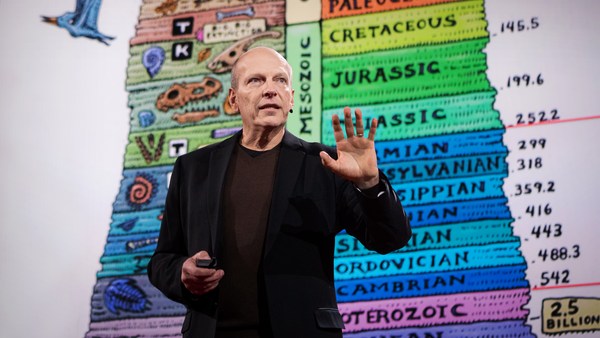

I am both a paleontologist and a comparative anatomist, and I am interested in understanding how the specialized dinosaur lung helped them take over the planet. So we are going to jump back over 200 million years to the Triassic period. The environment was extremely harsh, there were no flowering plants, so this means that there was no grass. So imagine a landscape filled with all pine trees and ferns. At the same time, there were small lizards, mammals, insects, and there were also carnivorous and herbivorous reptiles -- all competing for the same resources.

Critical to this story is that oxygen levels have been estimated to have been as low as 15 percent, compared to today's 21 percent. So it would have been crucial for dinosaurs to be able to breathe in this low-oxygen environment, not only to survive but to thrive and to diversify.

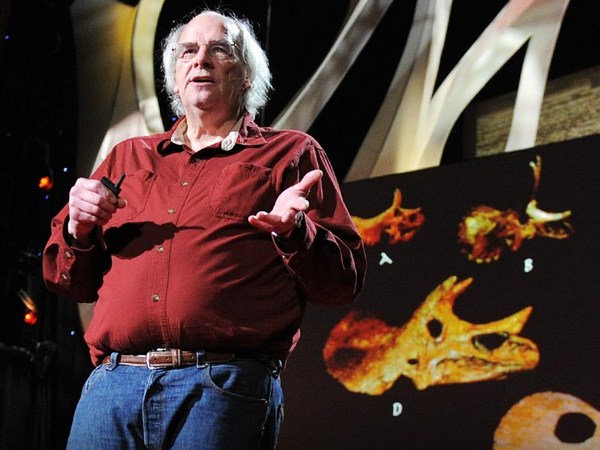

So, how do we know what dinosaur lungs were even like, since all that remains of a dinosaur generally is its fossilized skeleton? The method that we use is called "extant phylogenetic bracketing." This is a fancy way of saying that we study the anatomy -- specifically in this case, the lungs and skeleton -- of the living descendants of dinosaurs on the evolutionary tree. So we would look at the anatomy of birds, who are the direct descendants of dinosaurs, and we'd look at the anatomy of crocodilians, who are their closest living relatives, and then we would look at the anatomy of lizards and turtles, who we can think of like their cousins. And then we apply these anatomical data to the fossil record, and then we can use that to reconstruct the lungs of dinosaurs. And in this specific instance, the skeleton of dinosaurs most closely resembles that of modern birds.

So, because dinosaurs were competing with early mammals during this time period, it's important to understand the basic blueprint of the mammalian lung. Also, to reintroduce you to lungs in general, we will use my dog Mila of Troy, the face that launched a thousand treats, as our model.

(Laughter)

This story takes place inside of a chest cavity. So I want you to visualize the ribcage of a dog. Think about how the spinal vertebral column is completely horizontal to the ground. This is how the spinal vertebral column is going to be in all of the animals that we'll be talking about, whether they walked on two legs or four legs.

Now I want you to climb inside of the imaginary ribcage and look up. This is our thoracic ceiling. This is where the top surface of the lungs comes into direct contact with the ribs and vertebrae. This interface is where our story takes place. Now I want you to visualize the lungs of a dog. On the outside, it's like a giant inflatable bag where all parts of the bag expand during inhalation and contract during exhalation. Inside of the bag, there's a series of branching tubes, and these tubes are called the bronchial tree. These tubes deliver the inhaled oxygen to, ultimately, the alveolus. They cross over a thin membrane into the bloodstream by diffusion.

Now, this part is critical. The entire mammalian lung is mobile. That means it's moving during the entire respiratory process, so that thin membrane, the blood-gas barrier, cannot be too thin or it will break. Now, remember the blood-gas barrier, because we will be returning to this.

So, you're still with me? Because we're going to start birds and it gets crazy, so hold on to your butts. (Laughter) The bird is completely different from the mammal. And we are going to be using birds as our model to reconstruct the lungs of dinosaurs.

So in the bird, air passes through the lung, but the lung does not expand or contract. The lung is immobilized, it has the texture of a dense sponge and it's inflexible and locked into place on the top and sides by the ribcage and on the bottom by a horizontal membrane. It is then unidirectionally ventilated by a series of flexible, bag-like structures that branch off of the bronchial tree, beyond the lung itself, and these are called air sacs.

Now, this entire extremely delicate setup is locked into place by a series of forked ribs all along the thoracic ceiling. Also, in many species of birds, extensions arise from the lung and the air sacs, they invade the skeletal tissues -- usually the vertebrae, sometimes the ribs -- and they lock the respiratory system into place. And this is called "vertebral pneumaticity." The forked ribs and the vertebral pneumaticity are two clues that we can hunt for in the fossil record, because these two skeletal traits would indicate that regions of the respiratory system of dinosaurs are immobilized.

This anchoring of the respiratory system facilitated the evolution of the thinning of the blood-gas barrier, that thin membrane over which oxygen was diffusing into the bloodstream. The immobility permits this because a thin barrier is a weak barrier, and the weak barrier would rupture if it was actively being ventilated like a mammalian lung.

So why do we care about this? Why does this even matter? Oxygen more easily diffuses across a thin membrane, and a thin membrane is one way of enhancing respiration under low-oxygen conditions -- low-oxygen conditions like that of the Triassic period. So, if dinosaurs did indeed have this type of lung, they'd be better equipped to breathe than all other animals, including mammals.

So do you remember the extant phylogenetic bracket method where we take the anatomy of modern animals, and we apply that to the fossil record? So, clue number one was the forked ribs of modern birds. Well, we find that in pretty much the majority of dinosaurs. So that means that the top surface of the lungs of dinosaurs would be locked into place, just like modern birds.

Clue number two is vertebral pneumaticity. We find this in sauropod dinosaurs and theropod dinosaurs, which is the group that contains predatory dinosaurs and gave rise to modern birds. And while we don't find evidence of fossilized lung tissue in dinosaurs, vertebral pneumaticity gives us evidence of what the lung was doing during the life of these animals. Lung tissue or air sac tissue was invading the vertebrae, hollowing them out just like a modern bird, and locking regions of the respiratory system into place, immobilizing them. The forked ribs and the vertebral pneumaticity together were creating an immobilized, rigid framework that locked the respiratory system into place that permitted the evolution of that superthin, superdelicate blood-gas barrier that we see today in modern birds.

Evidence of this straightjacketed lung in dinosaurs means that they had the capability to evolve a lung that would have been able to breathe under the hypoxic, or low-oxygen, atmosphere of the Triassic period. This rigid skeletal setup in dinosaurs would have given them a significant adaptive advantage over other animals, particularly mammals, whose flexible lung couldn't have adapted to the hypoxic, or low-oxygen, atmosphere of the Triassic. This anatomy may have been the secret weapon of dinosaurs that gave them that advantage over other animals. And this gives us an excellent launchpad to start testing the hypotheses of dinosaurian diversification.

This is the story of the dinosaurs' beginning, and it's just the beginning of the story of our research into this subject.

Thank you.

(Applause)