"People do stupid things. That's what spreads HIV." This was a headline in a U.K. newspaper, The Guardian, not that long ago. I'm curious, show of hands, who agrees with it? Well, one or two brave souls.

This is actually a direct quote from an epidemiologist who's been in field of HIV for 15 years, worked on four continents, and you're looking at her.

And I am now going to argue that this is only half true. People do get HIV because they do stupid things, but most of them are doing stupid things for perfectly rational reasons. Now, "rational" is the dominant paradigm in public health, and if you put your public health nerd glasses on, you'll see that if we give people the information that they need about what's good for them and what's bad for them, if you give them the services that they can use to act on that information, and a little bit of motivation, people will make rational decisions and live long and healthy lives. Wonderful.

That's slightly problematic for me because I work in HIV, and although I'm sure you all know that HIV is about poverty and gender inequality, and if you were at TED '07 it's about coffee prices ... Actually, HIV's about sex and drugs, and if there are two things that make human beings a little bit irrational, they are erections and addiction.

(Laughter)

So, let's start with what's rational for an addict. Now, I remember speaking to an Indonesian friend of mine, Frankie. We were having lunch and he was telling me about when he was in jail in Bali for a drug injection. It was someone's birthday, and they had very kindly smuggled some heroin into jail, and he was very generously sharing it out with all of his colleagues. And so everyone lined up, all the smackheads in a row, and the guy whose birthday it was filled up the fit, and he went down and started injecting people. So he injects the first guy, and then he's wiping the needle on his shirt, and he injects the next guy. And Frankie says, "I'm number 22 in line, and I can see the needle coming down towards me, and there is blood all over the place. It's getting blunter and blunter. And a small part of my brain is thinking, 'That is so gross and really dangerous,' but most of my brain is thinking, 'Please let there be some smack left by the time it gets to me. Please let there be some left.'" And then, telling me this story, Frankie said, "You know ... God, drugs really make you stupid."

And, you know, you can't fault him for accuracy. But, actually, Frankie, at that time, was a heroin addict and he was in jail. So his choice was either to accept that dirty needle or not to get high. And if there's one place you really want to get high, it's when you're in jail.

But I'm a scientist and I don't like to make data out of anecdotes, so let's look at some data. We talked to 600 drug addicts in three cities in Indonesia, and we said, "Well, do you know how you get HIV?" "Oh yeah, by sharing needles." I mean, nearly 100 percent. Yeah, by sharing needles. And, "Do you know where you can get a clean needle at a price you can afford to avoid that?" "Oh yeah." Hundred percent. "We're smackheads; we know where to get clean needles." "So are you carrying a needle?" We're actually interviewing people on the street, in the places where they're hanging out and taking drugs. "Are you carrying clean needles?" One in four, maximum. So no surprises then that the proportion that actually used clean needles every time they injected in the last week is just about one in 10, and the other nine in 10 are sharing.

So you've got this massive mismatch; everyone knows that if they share they're going to get HIV, but they're all sharing anyway. So what's that about? Is it like you get a better high if you share or something? We asked that to a junkie and they're like, "Are you nuts?" You don't want to share a needle anymore than you want to share a toothbrush even with someone you're sleeping with. There's just kind of an ick factor there. "No, no. We share needles because we don't want to go to jail." So, in Indonesia at this time, if you were carrying a needle and the cops rounded you up, they could put you into jail. And that changes the equation slightly, doesn't it? Because your choice now is either I use my own needle now, or I could share a needle now and get a disease that's going to possibly kill me 10 years from now, or I could use my own needle now and go to jail tomorrow. And while junkies think that it's a really bad idea to expose themselves to HIV, they think it's a much worse idea to spend the next year in jail where they'll probably end up in Frankie's situation and expose themselves to HIV anyway. So, suddenly it becomes perfectly rational to share needles.

Now, let's look at it from a policy maker's point of view. This is a really easy problem. For once, your incentives are aligned. We've got what's rational for public health. You want people to use clean needles -- and junkies want to use clean needles. So we could make this problem go away simply by making clean needles universally available and taking away the fear of arrest. Now, the first person to figure that out and do something about it on a national scale was that well-known, bleeding heart liberal Margaret Thatcher. And she put in the world's first national needle exchange program, and other countries followed suit: Australia, The Netherlands and few others. And in all of those countries, you can see, not more than four percent of injectors ever became infected with HIV.

Now, places that didn't do this -- New York City for example, Moscow, Jakarta -- we're talking, at its peak, one in two injectors infected with this fatal disease. Now, Margaret Thatcher didn't do this because she has any great love for junkies. She did it because she ran a country that had a national health service. So, if she didn't invest in effective prevention, she was going to have pick up the costs of treatment later on, and obviously those are much higher. So she was making a politically rational decision. Now, if I take out my public health nerd glasses here and look at these data, it seems like a no-brainer, doesn't it? But in this country, where the government apparently does not feel compelled to provide health care for citizens, (Laughter) we've taken a very different approach. So what we've been doing in the United States is reviewing the data -- endlessly reviewing the data. So, these are reviews of hundreds of studies by all the big muckety-mucks of the scientific pantheon in the United States, and these are the studies that show needle programs are effective -- quite a lot of them. Now, the ones that show that needle programs aren't effective -- you think that's one of these annoying dynamic slides and I'm going to press my dongle and the rest of it's going to come up, but no -- that's the whole slide.

(Laughter)

There is nothing on the other side. So, completely irrational, you would think. Except that, wait a minute, politicians are rational, too, and they're responding to what they think the voters want. So what we see is that voters respond very well to things like this and not quite so well to things like this.

(Laughter)

So it becomes quite rational to deny services to injectors. Now let's talk about sex. Are we any more rational about sex? Well, I'm not even going to address the clearly irrational positions of people like the Catholic Church, who think somehow that if you give out condoms, everyone's going to run out and have sex. I don't know if Pope Benedict watches TEDTalks online, but if you do, I've got news for you Benedict -- I carry condoms all the time and I never get laid. (Laughter) (Applause) It's not that easy! Here, maybe you'll have better luck.

(Applause)

Okay, seriously, HIV is actually not that easy to transmit sexually. So, it depends on how much virus there is in your blood and in your body fluids. And what we've got is a very, very high level of virus right at the beginning when you're first infected, then you start making antibodies, and then it bumps along at quite low levels for a long time -- 10 or 12 years -- you have spikes if you get another sexually transmitted infection. But basically, nothing much is going on until you start to get symptomatic AIDS, and by that stage, you're not looking great, you're not feeling great, you're not having that much sex.

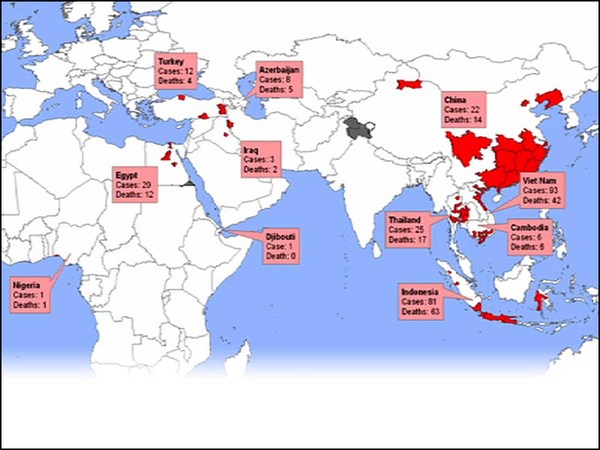

So the sexual transmission of HIV is essentially determined by how many partners you have in these very short spaces of time when you have peak viremia. Now, this makes people crazy because it means that you have to talk about some groups having more sexual partners in shorter spaces of time than other groups, and that's considered stigmatizing. I've always been a bit curious about that because I think stigma is a bad thing, whereas lots of sex is quite a good thing, but we'll leave that be. The truth is that 20 years of very good research have shown us that there are groups that are more likely to turnover large numbers of partners in a short space of time. And those groups are, globally, people who sell sex and their more regular partners. They are gay men on the party scene who have, on average, three times more partners than straight people on the party scene. And they are heterosexuals who come from countries that have traditions of polygamy and relatively high levels of female autonomy, and almost all of those countries are in east or southern Africa. And that is reflected in the epidemic that we have today.

You can see these horrifying figures from Africa. These are all countries in southern Africa where between one in seven, and one in three of all adults, are infected with HIV. Now, in the rest of the world, we've got basically nothing going on in the general population -- very, very low levels -- but we have extraordinarily high levels of HIV in these other populations who are at highest risk: drug injectors, sex workers and gay men. And you'll note, that's the local data from Los Angeles: 25 percent prevalence among gay men. Of course, you can't get HIV just by having unprotected sex. You can only HIV by having unprotected sex with a positive person.

In most of the world, these few prevention failures notwithstanding, we are actually doing quite well these days in commercial sex: condom use rates are between 80 and 100 percent in commercial sex in most countries. And, again, it's because of an alignment of the incentives. What's rational for public health is also rational for individual sex workers because it's really bad for business to have another STI. No one wants it. And, actually, clients don't want to go home with a drip either. So essentially, you're able to achieve quite high rates of condom use in commercial sex.

But in "intimate" relations it's much more difficult because, with your wife or your boyfriend or someone that you hope might turn into one of those things, we have this illusion of romance and trust and intimacy, and nothing is quite so unromantic as the, "My condom or yours, darling?" question. So in the face of that, you really need quite a strong incentive to use condoms.

This, for example, this gentleman is called Joseph. He's from Haiti and he has AIDS. And he's probably not having a lot of sex right now, but he is a reminder in the population, of why you might want to be using condoms. This is also in Haiti and is a reminder of why you might want to be having sex, perhaps. Now, funnily enough, this is also Joseph after six months on antiretroviral treatment. Not for nothing do we call it the Lazarus Effect. But it is changing the equation of what's rational in sexual decision-making. So, what we've got -- some people say, "Oh, it doesn't matter very much because, actually, treatment is effective prevention because it lowers your viral load and therefore makes it more difficult to transmit HIV." So, if you look at the viremia thing again, if you do start treatment when you're sick, well, what happens? Your viral load comes down. But compared to what? What happens if you're not on treatment? Well, you die, so your viral load goes to zero. And all of this green stuff here, including the spikes -- which are because you couldn't get to the pharmacy, or you ran out of drugs, or you went on a three day party binge and forgot to take your drugs, or because you've started to get resistance, or whatever -- all of that is virus that wouldn't be out there, except for treatment.

Now, am I saying, "Oh, well, great prevention strategy. Let's just stop treating people." Of course not, of course not. We need to expand antiretroviral treatment as much as we can. But what I am doing is calling into question those people who say that more treatment is all the prevention we need. That's simply not necessarily true, and I think we can learn a lot from the experience of gay men in rich countries where treatment has been widely available for going on 15 years now. And what we've seen is that, actually, condom use rates, which were very, very high -- the gay community responded very rapidly to HIV, with extremely little help from public health nerds, I would say -- that condom use rate has come down dramatically since treatment for two reasons really: One is the assumption of, "Oh well, if he's infected, he's probably on meds, and his viral load's going to be low, so I'm pretty safe."

And the other thing is that people are simply not as scared of HIV as they were of AIDS, and rightly so. AIDS was a disfiguring disease that killed you, and HIV is an invisible virus that makes you take a pill every day. And that's boring, but is it as boring as having to use a condom every time you have sex, no matter how drunk you are, no matter how many poppers you've taken, whatever? If we look at the data, we can see that the answer to that question is, mmm.

So these are data from Scotland. You see the peak in drug injectors before they started the national needle exchange program. Then it came way down. And both in heterosexuals -- mostly in commercial sex -- and in drug users, you've really got nothing much going on after treatment begins, and that's because of that alignment of incentives that I talked about earlier. But in gay men, you've got quite a dramatic rise starting three or four years after treatment became widely available. This is of new infections.

What does that mean? It means that the combined effect of being less worried and having more virus out there in the population -- more people living longer, healthier lives, more likely to be getting laid with HIV -- is outweighing the effects of lower viral load, and that's a very worrisome thing. What does it mean? It means we need to be doing more prevention the more treatment we have.

Is that what's happening? No, and I call it the "compassion conundrum." We've talked a lot about compassion the last couple of days, and what's happening really is that people are unable quite to bring themselves to put in good sexual and reproductive health services for sex workers, unable quite to be giving out needles to junkies. But once they've gone from being transgressive people whose behaviors we don't want to condone to being AIDS victims, we come over all compassionate and buy them incredibly expensive drugs for the rest of their lives. It doesn't make any sense from a public health point of view.

I want to give what's very nearly the last word to Ines. Ines is a a transgender hooker on the streets of Jakarta; she's a chick with a dick. Why does she do that job? Well, of course, because she's forced into it because she doesn't have any better option, etc., etc. And if we could just teach her to sew and get her a nice job in a factory, all would be well. This is what factory workers earn in an hour in Indonesia: on average, 20 cents. It varies a bit province to province. I do speak to sex workers, 15,000 of them for this particular slide, and this is what sex workers say they earn in an hour. So it's not a great job, but for a lot of people it really is quite a rational choice. Okay, Ines.

We've got the tools, the knowledge and the cash, and commitment to preventing HIV too.

Ines: So why is prevalence still rising? It's all politics. When you get to politics, nothing makes sense.

Elizabeth Pisani: "When you get to politics, nothing makes sense." So, from the point of view of a sex worker, politicians are making no sense. From the point of view of a public health nerd, junkies are doing dumb things. The truth is that everyone has a different rationale. There are as many different ways of being rational as there are human beings on the planet, and that's one of the glories of human existence. But those ways of being rational are not independent of one another, so it's rational for a drug injector to share needles because of a stupid decision that's made by a politician, and it's rational for a politician to make that stupid decision because they're responding to what they think the voters want. But here's the thing: we are the voters. We're not all of them, of course, but TED is a community of opinion leaders. And everyone who's in this room, and everyone who's watching this out there on the web, I think, has a duty to demand of their politicians that we make policy based on scientific evidence and on common sense. It's going to be really hard for us to individually affect what's rational for every Frankie and every Ines out there, but you can at least use your vote to stop politicians doing stupid things that spread HIV.

Thank you.

(Applause)