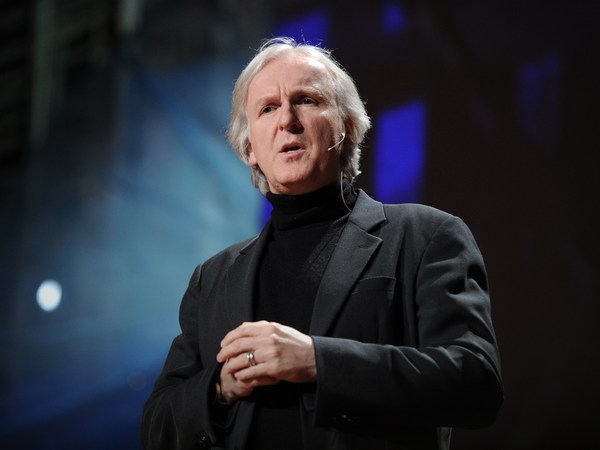

I'm here today representing a team of artists and technologists and filmmakers that worked together on a remarkable film project for the last four years. And along the way they created a breakthrough in computer visualization.

So I want to show you a clip of the film now. Hopefully it won't stutter. And if we did our jobs well, you won't know that we were even involved.

Voice (Video): I don't know how it's possible ... but you seem to have more hair.

Brad Pitt: What if I told you that I wasn't getting older ... but I was getting younger than everybody else?

I was born with some form of disease.

Voice: What kind of disease?

BP: I was born old.

Man: I'm sorry.

BP: No need to be. There's nothing wrong with old age.

Girl: Are you sick?

BP: I heard momma and Tizzy whisper, and they said I was gonna die soon. But ... maybe not.

Girl: You're different than anybody I've ever met.

BB: There were many changes ... some you could see, some you couldn't. Hair started growing in all sorts of places, along with other things. I felt pretty good, considering.

Ed Ulbrich: That was a clip from "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button." Many of you, maybe you've seen it or you've heard of the story, but what you might not know is that for nearly the first hour of the film, the main character, Benjamin Button, who's played by Brad Pitt, is completely computer-generated from the neck up. Now, there's no use of prosthetic makeup or photography of Brad superimposed over another actor's body. We've created a completely digital human head.

So I'd like to start with a little bit of history on the project. This is based on an F. Scott Fitzgerald short story. It's about a man who's born old and lives his life in reverse. Now, this movie has floated around Hollywood for well over half a century, and we first got involved with the project in the early '90s, with Ron Howard as the director. We took a lot of meetings and we seriously considered it. But at the time we had to throw in the towel. It was deemed impossible. It was beyond the technology of the day to depict a man aging backwards. The human form, in particular the human head, has been considered the Holy Grail of our industry.

The project came back to us about a decade later, and this time with a director named David Fincher. Now, Fincher is an interesting guy. David is fearless of technology, and he is absolutely tenacious. And David won't take "no." And David believed, like we do in the visual effects industry, that anything is possible as long as you have enough time, resources and, of course, money. And so David had an interesting take on the film, and he threw a challenge at us. He wanted the main character of the film to be played from the cradle to the grave by one actor. It happened to be this guy.

We went through a process of elimination and a process of discovery with David, and we ruled out, of course, swapping actors. That was one idea: that we would have different actors, and we would hand off from actor to actor.

We even ruled out the idea of using makeup. We realized that prosthetic makeup just wouldn't hold up, particularly in close-up. And makeup is an additive process. You have to build the face up. And David wanted to carve deeply into Brad's face to bring the aging to this character. He needed to be a very sympathetic character. So we decided to cast a series of little people that would play the different bodies of Benjamin at the different increments of his life and that we would in fact create a computer-generated version of Brad's head, aged to appear as Benjamin, and attach that to the body of the real actor. Sounded great.

Of course, this was the Holy Grail of our industry, and the fact that this guy is a global icon didn't help either, because I'm sure if any of you ever stand in line at the grocery store, you know -- we see his face constantly. So there really was no tolerable margin of error. There were two studios involved: Warner Brothers and Paramount. And they both believed this would make an amazing film, of course, but it was a very high-risk proposition. There was lots of money and reputations at stake. But we believed that we had a very solid methodology that might work ...

But despite our verbal assurances, they wanted some proof. And so, in 2004, they commissioned us to do a screen test of Benjamin. And we did it in about five weeks. But we used lots of cheats and shortcuts. We basically put something together to get through the meeting. I'll roll that for you now. This was the first test for Benjamin Button. And in here, you can see, that's a computer-generated head -- pretty good -- attached to the body of an actor. And it worked. And it gave the studio great relief. After many years of starts and stops on this project, and making that tough decision, they finally decided to greenlight the movie. And I can remember, actually, when I got the phone call to congratulate us, to say the movie was a go, I actually threw up. (Laughter) You know, this is some tough stuff.

So we started to have early team meetings, and we got everybody together, and it was really more like therapy in the beginning, convincing each other and reassuring each other that we could actually undertake this. We had to hold up an hour of a movie with a character. And it's not a special effects film; it has to be a man. We really felt like we were in a -- kind of a 12-step program. And of course, the first step is: admit you've got a problem. (Laughter) So we had a big problem: we didn't know how we were going to do this. But we did know one thing. Being from the visual effects industry, we, with David, believed that we now had enough time, enough resources, and, God, we hoped we had enough money. And we had enough passion to will the processes and technology into existence.

So, when you're faced with something like that, of course you've got to break it down. You take the big problem and you break it down into smaller pieces and you start to attack that. So we had three main areas that we had to focus on. We needed to make Brad look a lot older -- needed to age him 45 years or so. And we also needed to make sure that we could take Brad's idiosyncrasies, his little tics, the little subtleties that make him who he is and have that translate through our process so that it appears in Benjamin on the screen.

And we also needed to create a character that could hold up under, really, all conditions. He needed to be able to walk in broad daylight, at nighttime, under candlelight, he had to hold an extreme close-up, he had to deliver dialogue, he had to be able to run, he had to be able to sweat, he had to be able to take a bath, to cry, he even had to throw up. Not all at the same time -- but he had to, you know, do all of those things.

And the work had to hold up for almost the first hour of the movie. We did about 325 shots. So we needed a system that would allow Benjamin to do everything a human being can do. And we realized that there was a giant chasm between the state of the art of technology in 2004 and where we needed it to be.

So we focused on motion capture. I'm sure many of you have seen motion capture. The state of the art at the time was something called marker-based motion capture. I'll give you an example here. It's basically the idea of, you wear a leotard, and they put some reflective markers on your body, and instead of using cameras, there're infrared sensors around a volume, and those infrared sensors track the three-dimensional position of those markers in real time. And then animators can take the data of the motion of those markers and apply them to a computer-generated character. You can see the computer characters on the right are having the same complex motion as the dancers.

But we also looked at numbers of other films at the time that were using facial marker tracking, and that's the idea of putting markers on the human face and doing the same process. And as you can see, it gives you a pretty crappy performance. That's not terribly compelling. And what we realized was that what we needed was the information that was going on between the markers. We needed the subtleties of the skin. We needed to see skin moving over muscle moving over bone. We needed creases and dimples and wrinkles and all of those things.

Our first revelation was to completely abort and walk away from the technology of the day, the status quo, the state of the art. So we aborted using motion capture. And we were now well out of our comfort zone, and in uncharted territory. So we were left with this idea that we ended up calling "technology stew." We started to look out in other fields. The idea was that we were going to find nuggets or gems of technology that come from other industries like medical imaging, the video game space, and re-appropriate them. And we had to create kind of a sauce. And the sauce was code in software that we'd written to allow these disparate pieces of technology to come together and work as one.

Initially, we came across some remarkable research done by a gentleman named Dr. Paul Ekman in the early '70s. He believed that he could, in fact, catalog the human face. And he came up with this idea of Facial Action Coding System, or FACS. He believed that there were 70 basic poses or shapes of the human face, and that those basic poses or shapes of the face can be combined to create infinite possibilities of everything the human face is capable of doing. And of course, these transcend age, race, culture, gender. So this became the foundation of our research as we went forward.

And then we came across some remarkable technology called Contour. And here you can see a subject having phosphorus makeup stippled on her face. And now what we're looking at is really creating a surface capture as opposed to a marker capture. The subject stands in front of a computer array of cameras, and those cameras can, frame-by-frame, reconstruct the geometry of exactly what the subject's doing at the moment. So, effectively, you get 3D data in real time of the subject. And if you look in a comparison, on the left, we see what volumetric data gives us and on the right you see what markers give us. So, clearly, we were in a substantially better place for this. But these were the early days of this technology, and it wasn't really proven yet. We measure complexity and fidelity of data in terms of polygonal count. And so, on the left, we were seeing 100,000 polygons. We could go up into the millions of polygons. It seemed to be infinite.

This was when we had our "Aha!" This was the breakthrough. This is when we're like, "OK, we're going to be OK, This is actually going to work." And the "Aha!" was, what if we could take Brad Pitt, and we could put Brad in this device, and use this Contour process, and we could stipple on this phosphorescent makeup and put him under the black lights, and we could, in fact, scan him in real time performing Ekman's FACS poses. Right? So, effectively, we ended up with a 3D database of everything Brad Pitt's face is capable of doing. (Laughter)

From there, we actually carved up those faces into smaller pieces and components of his face. So we ended up with literally thousands and thousands and thousands of shapes, a complete database of all possibilities that his face is capable of doing.

Now, that's great, except we had him at age 44. We need to put another 40 years on him at this point. We brought in Rick Baker, and Rick is one of the great makeup and special effects gurus of our industry. And we also brought in a gentleman named Kazu Tsuji, and Kazu Tsuji is one of the great photorealist sculptors of our time. And we commissioned them to make a maquette, or a bust, of Benjamin. So, in the spirit of "The Great Unveiling" -- I had to do this -- I had to unveil something. So this is Ben 80. We created three of these: there's Ben 80, there's Ben 70, there's Ben 60. And this really became the template for moving forward.

Now, this was made from a life cast of Brad. So, in fact, anatomically, it is correct. The eyes, the jaw, the teeth: everything is in perfect alignment with what the real guy has. We have these maquettes scanned into the computer at very high resolution -- enormous polygonal count. And so now we had three age increments of Benjamin in the computer.

But we needed to get a database of him doing more than that. We went through this process, then, called retargeting. This is Brad doing one of the Ekman FACS poses. And here's the resulting data that comes from that, the model that comes from that. Retargeting is the process of transposing that data onto another model. And because the life cast, or the bust -- the maquette -- of Benjamin was made from Brad, we could transpose the data of Brad at 44 onto Brad at 87. So now, we had a 3D database of everything Brad Pitt's face can do at age 87, in his 70s and in his 60s.

Next we had to go into the shooting process. So while all that's going on, we're down in New Orleans and locations around the world. And we shot our body actors, and we shot them wearing blue hoods. So these are the gentleman who played Benjamin. And the blue hoods helped us with two things: one, we could easily erase their heads; and we also put tracking markers on their heads so we could recreate the camera motion and the lens optics from the set.

But now we needed to get Brad's performance to drive our virtual Benjamin. And so we edited the footage that was shot on location with the rest of the cast and the body actors and about six months later we brought Brad onto a sound stage in Los Angeles and he watched on the screen. His job, then, was to become Benjamin. And so we looped the scenes. He watched again and again. We encouraged him to improvise. And he took Benjamin into interesting and unusual places that we didn't think he was going to go. We shot him with four HD cameras so we'd get multiple views of him and then David would choose the take of Brad being Benjamin that he thought best matched the footage with the rest of the cast.

From there we went into a process called image analysis. And so here, you can see again, the chosen take. And you are seeing, now, that data being transposed on to Ben 87. And so, what's interesting about this is we used something called image analysis, which is taking timings from different components of Benjamin's face. And so we could choose, say, his left eyebrow. And the software would tell us that, well, in frame 14 the left eyebrow begins to move from here to here, and it concludes moving in frame 32. And so we could choose numbers of positions on the face to pull that data from.

And then, the sauce I talked about with our technology stew -- that secret sauce was, effectively, software that allowed us to match the performance footage of Brad in live action with our database of aged Benjamin, the FACS shapes that we had. On a frame-by-frame basis, we could actually reconstruct a 3D head that exactly matched the performance of Brad.

So this was how the finished shot appeared in the film. And here you can see the body actor. And then this is what we called the "dead head," no reference to Jerry Garcia.

And then here's the reconstructed performance now with the timings of the performance. And then, again, the final shot. It was a long process. (Applause)

The next section here, I'm going to just blast through this, because we could do a whole TEDTalk on the next several slides.

We had to create a lighting system. So really, a big part of our processes was creating a lighting environment for every single location that Benjamin had to appear so that we could put Ben's head into any scene and it would exactly match the lighting that's on the other actors in the real world.

We also had to create an eye system. We found the old adage, you know, "The eyes are the window to the soul," absolutely true. So the key here was to keep everybody looking in Ben's eyes. And if you could feel the warmth, and feel the humanity, and feel his intent coming through the eyes, then we would succeed. So we had one person focused on the eye system for almost two full years.

We also had to create a mouth system. We worked from dental molds of Brad. We had to age the teeth over time.

We also had to create an articulating tongue that allowed him to enunciate his words. There was a whole system written in software to articulate the tongue. We had one person devoted to the tongue for about nine months. He was very popular.

Skin displacement: another big deal. The skin had to be absolutely accurate. He's also in an old age home, he's in a nursing home around other old people, so he had to look exactly the same as the others. So, lots of work on skin deformation, you can see in some of these cases it works, in some cases it looks bad. This is a very, very, very early test in our process. So, effectively we created a digital puppet that Brad Pitt could operate with his own face. There were no animators necessary to come in and interpret behavior or enhance his performance.

There was something that we encountered, though, that we ended up calling "the digital Botox effect." So, as things went through this process, Fincher would always say, "It sandblasts the edges off of the performance." And thing our process and the technology couldn't do, is they couldn't understand intent, the intent of the actor. So it sees a smile as a smile. It doesn't recognize an ironic smile, or a happy smile, or a frustrated smile. So it did take humans to kind of push it one way or another.

But we ended up calling the entire process and all the technology "emotion capture," as opposed to just motion capture. Take another look.

Brad Pitt: Well, I heard momma and Tizzy whisper, and they said I was gonna die soon, but ... maybe not.

EU: That's how to create a digital human in 18 minutes. (Applause)

A couple of quick factoids; it really took 155 people over two years, and we didn't even talk about 60 hairstyles and an all-digital haircut. But, that is Benjamin. Thank you.