I wanted to talk to you today about creative confidence. I'm going to start way back in the third grade at Oakdale School in Barberton, Ohio.

I remember one day my best friend Brian was working on a project. He was making a horse out of the clay our teacher kept under the sink. And at one point, one of the girls that was sitting at his table, seeing what he was doing, leaned over and said to him, "That's terrible. That doesn't look anything like a horse." And Brian's shoulders sank. And he wadded up the clay horse and he threw it back in the bin. I never saw Brian do a project like that ever again.

And I wonder how often that happens, you know? It seems like when I tell that story of Brian to my class, a lot of them want to come up after class and tell me about their similar experience, how a teacher shut them down, or how a student was particularly cruel to them. And then some kind of opt out of thinking of themselves as creative at that point. And I see that opting out that happens in childhood, and it moves in and becomes more ingrained, even, by the time you get to adult life.

So we see a lot of this. When we have a workshop or when we have clients in to work with us side by side, eventually we get to the point in the process that's kind of fuzzy or unconventional. And eventually, these big-shot executives whip out their BlackBerrys and they say they have to make really important phone calls, and they head for the exits. And they're just so uncomfortable. When we track them down and ask them what's going on, they say something like, "I'm just not the creative type." But we know that's not true. If they stick with the process, if they stick with it, they end up doing amazing things. And they surprise themselves at just how innovative they and their teams really are.

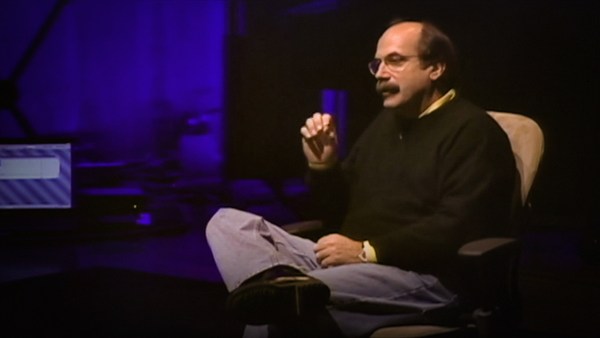

So I've been looking at this fear of judgment that we have, that you don't do things, you're afraid you're going to be judged; if you don't say the right creative thing, you're going to be judged. And I had a major breakthrough, when I met the psychologist Albert Bandura.

I don't know if you know Albert Bandura, but if you go to Wikipedia, it says that he's the fourth most important psychologist in history -- you know, like Freud, Skinner, somebody and Bandura.

(Laughter)

Bandura is 86 and he still works at Stanford. And he's just a lovely guy.

So I went to see him, because he's just worked on phobias for a long time, which I'm very interested in. He had developed this way, this, kind of, methodology, that ended up curing people in a very short amount of time, like, in four hours. He had a huge cure rate of people who had phobias. And we talked about snakes -- I don't know why -- we talked about snakes and fear of snakes as a phobia.

And it was really enjoyable, really interesting. He told me that he'd invite the test subject in, and he'd say, "You know, there's a snake in the next room and we're going to go in there." To which, he reported, most of them replied, "Hell no! I'm not going in there, certainly if there's a snake in there."

But Bandura has a step-by-step process that was super successful. So he'd take people to this two-way mirror looking into the room where the snake was. And he'd get them comfortable with that. Then through a series of steps, he'd move them and they'd be standing in the doorway with the door open, and they'd be looking in there. And he'd get them comfortable with that. And then many more steps later, baby steps, they'd be in the room, they'd have a leather glove like a welder's glove on, and they'd eventually touch the snake. And when they touched the snake, everything was fine. They were cured. In fact, everything was better than fine. These people who had lifelong fears of snakes were saying things like, "Look how beautiful that snake is." And they were holding it in their laps.

Bandura calls this process "guided mastery." I love that term: guided mastery. And something else happened. These people who went through the process and touched the snake ended up having less anxiety about other things in their lives. They tried harder, they persevered longer, and they were more resilient in the face of failure. They just gained a new confidence. And Bandura calls that confidence "self-efficacy," the sense that you can change the world and that you can attain what you set out to do.

Well, meeting Bandura was really cathartic for me, because I realized that this famous scientist had documented and scientifically validated something that we've seen happen for the last 30 years: that we could take people who had the fear that they weren't creative, and we could take them through a series of steps, kind of like a series of small successes, and they turn fear into familiarity. And they surprise themselves. That transformation is amazing.

We see it at the d.school all the time. People from all different kinds of disciplines, they think of themselves as only analytical. And they come in and they go through the process, our process, they build confidence and now they think of themselves differently. And they're totally emotionally excited about the fact that they walk around thinking of themselves as a creative person.

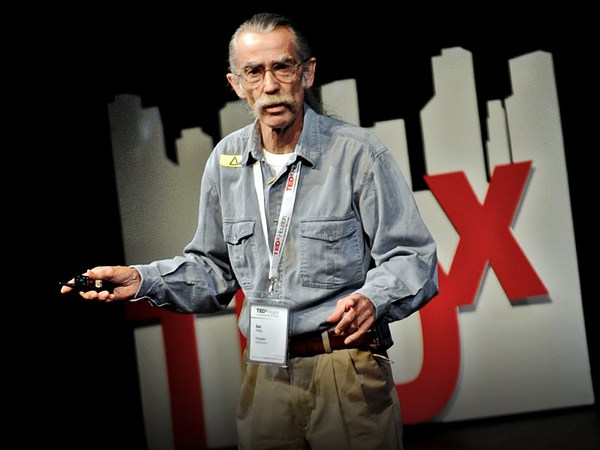

So I thought one of the things I'd do today is take you through and show you what this journey looks like. To me, that journey looks like Doug Dietz. Doug Dietz is a technical person. He designs large medical imaging equipment. He's worked for GE, and he's had a fantastic career. But at one point, he had a moment of crisis.

He was in the hospital looking at one of his MRI machines in use, when he saw a young family, and this little girl. And that little girl was crying and was terrified. And Doug was really disappointed to learn that nearly 80 percent of the pediatric patients in this hospital had to be sedated in order to deal with his MRI machine. And this was really disappointing to Doug, because before this time, he was proud of what he did. He was saving lives with this machine. But it really hurt him to see the fear that this machine caused in kids.

About that time, he was at the d.school at Stanford taking classes. He was learning about our process, about design thinking, about empathy, about iterative prototyping. And he would take this new knowledge and do something quite extraordinary. He would redesign the entire experience of being scanned. And this is what he came up with.

(Laughter)

He turned it into an adventure for the kids. He painted the walls and he painted the machine, and he got the operators retrained by people who know kids, like children's museum people. And now when the kid comes, it's an experience. And they talk to them about the noise and the movement of the ship. And when they come, they say, "OK, you're going to go into the pirate ship, but be very still, because we don't want the pirates to find you."

And the results were super dramatic: from something like 80 percent of the kids needing to be sedated, to something like 10 percent of the kids needing to be sedated. And the hospital and GE were happy, too, because you didn't have to call the anesthesiologist all the time, and they could put more kids through the machine in a day. So the quantitative results were great. But Doug's results that he cared about were much more qualitative. He was with one of the mothers waiting for her child to come out of the scan. And when the little girl came out of her scan, she ran up to her mother and said, "Mommy, can we come back tomorrow?"

(Laughter)

And so, I've heard Doug tell the story many times of his personal transformation and the breakthrough design that happened from it, but I've never really seen him tell the story of the little girl without a tear in his eye.

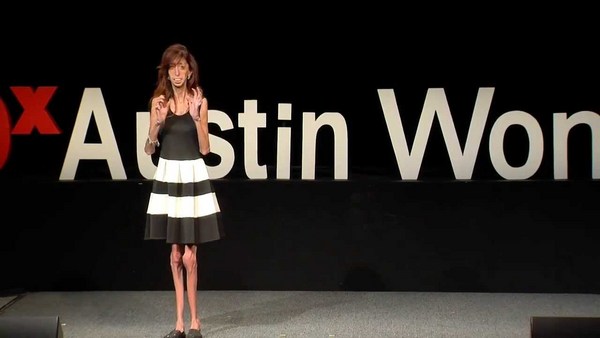

Doug's story takes place in a hospital. I know a thing or two about hospitals. A few years ago, I felt a lump on the side of my neck. It was my turn in the MRI machine. It was cancer, it was the bad kind. I was told I had a 40 percent chance of survival.

So while you're sitting around with the other patients, in your pajamas, and everybody's pale and thin --

(Laughter)

you know? -- and you're waiting for your turn to get the gamma rays, you think of a lot of things. Mostly, you think about: Am I going to survive? And I thought a lot about: What was my daughter's life going to be like without me? But you think about other things. I thought a lot about: What was I put on Earth to do? What was my calling? What should I do? I was lucky because I had lots of options. We'd been working in health and wellness, and K-12, and the developing world. so there were lots of projects that I could work on. But then I decided and committed at this point, to the thing I most wanted to do, which was to help as many people as possible regain the creative confidence they lost along their way. And if I was going to survive, that's what I wanted to do. I survived, just so you know.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

I really believe that when people gain this confidence -- and we see it all the time at the d.school and at IDEO -- that they actually start working on the things that are really important in their lives. We see people quit what they're doing and go in new directions. We see them come up with more interesting -- and just more -- ideas, so they can choose from better ideas. And they just make better decisions.

I know at TED, you're supposed to have a change-the-world kind of thing, isn't that -- everybody has a change-the-world thing? If there is one for me, this is it, to help this happen. So I hope you'll join me on my quest, you as, kind of, thought leaders. It would be really great if you didn't let people divide the world into the creatives and the non-creatives, like it's some God-given thing, and to have people realize that they're naturally creative, and that those natural people should let their ideas fly; that they should achieve what Bandura calls self-efficacy, that you can do what you set out to do, and that you can reach a place of creative confidence and touch the snake.

Thank you.

(Applause)