You are about to hear the sounds of the largest-toothed predator on the planet: an animal bigger than a school bus with perhaps the most sophisticated form of communication that has ever existed.

(Video: whale clicking)

These are the sounds of the mighty sperm whale, a fellow mammal that can dive almost a mile, hold its breath for more than an hour and lives in these amazingly complex, matriarchal societies. These clicks you heard, called codas, are just a facet of what we know of their communication. We know these animals are communicating, we just don't yet know what they're saying.

Project CETI aims to find out. Over the next five years, our team of AI specialists, roboticists, linguists and marine biologists aim to use the most cutting-edge technologies to make contact with another species, and hopefully communicate back. We believe that by listening deeply to nature, we can change our perspective of ourselves and reshape our relationship with all life on this planet.

This of course seems like an impossible goal. People have been trying to make contact with other animals for hundreds of years. How could we do what others could not, especially given that I'm sitting here on my couch in New York City in the middle of a pandemic and protests?

I've spent the last 20 years as a marine biologist and oceanographer, studying the ocean from all different perspectives, from microbes to sharks. I've assembled interdisciplinary teams that have built the first shark-eye camera to see the world from a shark's perspective, and have collaborated with engineers to design robots so gentle that they don't even stress a jellyfish. But it wasn't until 2018 when I was on fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study that I realized that perhaps the best way to understand the ocean and its inhabitants wasn't just by seeing the world through their eyes, but by listening -- by really, deeply listening.

I became interested in sperm whales when I heard their sounds. They sounded like they were coming from another universe; a siren song being broadcast from the darkest reaches of the sea. These weren't the typical harmonious whale songs that I had been accustomed to. These sounded more like digital data transfer. We assembled the future Project CETI team and began discussing how to use the most advanced technologies to communicate with whales. One of the principal conclusions was that machine learning had a really good chance of understanding the patterns of sperm whale communication. And the time to apply these technologies was now. Cracking the interspecies communication code didn't just seem possible, it almost seemed inevitable. But how can analyzing patterns help us converse with whales and other animals?

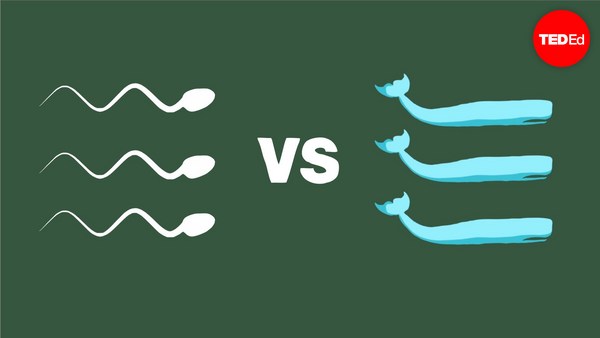

Well, step one is to understand the elements of sperm whale communication. These codas you heard don't appear to be sentences as we know them, but there's clear structure in how these animals communicate. Sperm whales send codas back and forth to each other in sequences, and there are regional dialects like British and Australian accents. This is exactly why machine learning is such a powerful tool. These approaches analyze patterns in relationship and map meaning to them. Just a few years ago, scientists used machine learning to translate between two totally unknown human languages. Not by using a Rosetta Stone or a dictionary, but by mapping them on patterns in higher-dimensional space. But for machine learning to work effectively, it needs data -- it needs lots and lots of data.

In the past half-century, marine researchers have painstakingly collected and hand annotated just a few thousand sperm whale vocalizations, but in order to learn sperm whale communication, we'll need to collect millions, if not tens of millions of carefully annotated sperm whale vocalizations correlated with behaviors. We'll do it with noninvasive, autonomous, free-swimming robots, aerial-aquatic drones, bottom-mounted hydrophone arrays and more.

We'll work with our close partners at the Dominica Sperm Whale Project to cover a 20-square-kilometer area that is frequented by over 25 well-known families of sperm whales. We're going to put specific focus on the interactions of mothers and calfs, training our machine learning algorithms to learn whale language from the bottom up. All this data we'll have sent through a pipeline and analyzed by the Project CETI translation team. The raw audio and context data will go through our machine learning engine where it's going to be first sorted by structure. The linguistics team will then search for things like syntax and time displacement. For example, if we find an event where a whale was talking about something yesterday, that alone would be a major finding, something that has thus far only been shown in humans. And once we've really mastered listening, we're going to try really carefully to talk back even on the most simplistic level.

Finally, Project CETI will build an open-source platform where we will make our data sets available to the public, encouraging the global community to come along on this journey for understanding. These animals could be the most intelligent beings on this planet. They have a neocortex and spindle cells -- structure that in humans control our higher thoughts, emotions, memory, language and love. And all the platforms that we develop can be cross-applied to other animals: to elephants, birds, primates, dolphins -- essentially any animal.

In the late 1960s, our team member, Roger Payne, discovered that whales sing.

(Recording: whale singing)

A finding that sparked the Save the Whales movement led to the end of large-scale whaling and prevented several whale species from extinction just by showing that whales sing. Imagine if we could understand what they're saying. Now is the time to open this larger dialogue. Now is the time to listen deeply and show these magical animals, and each other, newfound respect.

Thank you.