Thank you. Okay, people, let’s just get this out of the way, okay? Now, I know this isn’t a very comfortable subject for many of you, but I’ve got to say it: We have to talk about your fungus problem, okay? Now, it’s okay. Don’t be embarrassed. You know who you are. But we can work this out. We’ll get through it together. Now, call them fungi, “fungee,” “funguy.” You decide. But what I’d like to impress upon you is this is a new world we need to begin exploring, and I think we can do it in interesting ways. But all of us have had an issue with fungi at some point in our lives, right? Maybe even now? We think of fungi, we think of that fuzzy stuff that’s growing on our yogurt that we forgot in the back of the fridge, right? Or maybe that itch you developed by wearing that favorite pair of pants but just got a little bit too tight? Or, you know, maybe you think of death and decay and disease when you think about fungi. But fungi, yeah, maybe some of them have a dark side, I mean, who of us doesn’t? But I’d like to invite you to see these misunderstood creatures in a new light, and maybe start to appreciate some of the ways, some of the positive ways and inspirational ways that they behave. So if that mold is breaking bad on that yogurt that you forgot in the back of the fridge - again, right? - maybe it’s not just rotting and spoiling, but maybe it’s taking an act of transformation, of renewal and of new possibilities. And it’s that very act of transformation that’s both so central to life on our planet and has been important for our own history and maybe for the future. If we can learn from fungi, we might be able to transform ourselves and our societies in ways that are in greater harmony with nature. Now, what do I mean when I say fungi have been important to our past? I’m not talking about that amazing mushroom trip that you took back in university, though, yeah, that was probably pretty awesome in its own right. What I’m talking about is the way that fungi have been central to the evolution of life on the planet, that virtually all of life has a fungal backstory. Now, think, fungi have been on the planet for a billion years. A billion years or more. And during that time, you know, the Earth was just a rocky, desolate place. There was no life on it. Now, algae would actually escape the waters and come onto land to evolve into land plants but only by partnering with fungi first as its root system. Soils would begin to form as fungi ate rock and break down to make the nutrients available. So you have this opportunity for new life to spring up. And as a result, evolution of plants would explode across the planet, which would oxygenate the atmosphere and allow the evolution of more complex life-forms, like us humans. Right? So this ability, being on the planet for a billion years, fungi have developed all sorts of life strategies to be adaptive and diverse and resilient. I mean, think about it, that they survived a billion years through great swings in climate over hundreds of millions of years, lived through all the five great mass extinction events, where the dinosaurs went extinct and the poor little trilobites and countless other forms of life that we don’t even know they existed. But fungi persisted and thrived, and do to this day. And I think that’s what drove them to me. I mean, it’s so endearing, right? I mean, who doesn't love a good survival story? I know I do. But fungi weren’t my first love. That was music, actually. And actually, when I was a young boy, I was really into grunge music, and I played in a grunge band. And we were awful. (Laughter) But I didn’t know that at the time, and anyhow, I had to follow my passion. So I put everything in my pickup truck, and I moved from my childhood home of Kansas City to Seattle, the mecca of grunge music in the nineties. And I was going to start a new band. And unfortunately, none of the talent of Nirvana or Soundgarden rubbed off on me - it would have been a quite different life had it did - but the splendor of the Pacific Northwest forests really did. And it was the trees and all the life above ground that drew me there, but it was the fungi and the microbes below ground that kept me coming back. I just got even more and more interested about the way that they lived, all these bizarre forms, the fact that fungi are literally everywhere. Right now, they’re on your skin, in your gut. With every breath you take, you inhale dozens of fungal spores. Every move you make, you trample mushrooms and molds beneath your feet in the soil. And their ubiquity is a big reason why we know so little about fungi. Despite all the tools we have at our disposal, scientific tools, we know perhaps five percent of all the fungi, some 3 million species that are thought to exist in the world today. Now, that’s a massive amount of biodiversity that we know virtually nothing about, how it lives and what it does. And that's what really inspired me to continue to study about fungi and ask deeper questions. Could some of this biodiversity help in creating a more resilient future? Right? What could we actually learn from fungi? Were there metaphors that we might to apply to how we live to create a more resilient future together? Now, I’d like to share with you some of those metaphors. The first is that fungi are biointelligent. Now, being on the planet for so long, fungi have created a really great ability to be good at resource efficiency and resilience and, as it turns out, spatial planning. So researchers in Japan did this super cool experiment. They wanted to see if fungi could help engineers to create more efficient transport networks. So they laid out oatmeal on a petri dish, corresponding to the cities of the Tokyo metropolitan area, and they introduced a slime mold, a type of fungus whose favoritest food ever is oatmeal, and the fungus rapidly went through a process of self-optimization to find the most efficient links between its favoritest-ever food source, represented by a map of the Tokyo metropolitan area. And in a matter of hours, it would recreate, largely, the existing railway map of the Tokyo metropolitan area, a process it took engineers decades to actually produce. Now, the fungus, it has no brain. It has no plan. It was given no instructions or guidance, but still, it created a highly optimized network. And this convinced me and other scientists that maybe fungi could have practical applications to help solve some of our human challenges in ways that are quick and efficient and perhaps even more imaginative than we could do with all of our brains put together. Now, another way that fungi can produce a metaphor is being collaborative. Now, this is most evident in their relationships with plants. Now, remember how algae evolved into plants through the help of fungi and its root system? Well, that love affair never ended. Still today, 90 percent of all land plants need to have a mycorrhizal association. This is the plant-fungus-root association. So depicted here, in this highly realistic view of the underground of a forest ecosystem, you can see the fungus, which exists in most of its life as thin filaments and as a network of thin filaments. We call it mycelium. And the mycelium of the fungus can tap into the root of plants and make a symbiosis. And by there, they exchange nutrients that the other one isn’t so good at making or capturing. So the case of fungi, they’re providing minerals to the plants, and the case of the plants, through photosynthesis, they’re providing carbon. And so this exchange can go on between the organisms. But it doesn’t stop there, because the fungi can tap into other plants at the same time, and other plants can have also other fungal partners. So what you end up is this massive underground network mediated by fungi. Now, it’s not just nutrients that are flowing but also communication, because plants can talk to each other through the fungal network to create perhaps chemical signals to be able to warn of pest attack, for example. Now, fungi are also regenerative, right? Now, their ability to decompose is important for the planet, to say the least, because fungi eat death and give it back to life as nutrients to start the cycle anew. In nature, there’s no such thing as waste. I mean, waste is a human concept. Everything is used. Everything is circular. Everything becomes something else. And if you don’t appreciate fungi, you will for one reason, and it’s that decompositional ability. I mean, think about it. We would be buried under kilometers deep of undecayed plant matter and dead animals and poo without the decompositional ability of fungi, and that would be a pretty crappy existence, you got to admit. So as a metaphor, fungi can provide us with ways of being biointelligent, collaborative and resilient. But I also believe that fungi have practical implications in how we produce materials. And this is actually my very cool day job as researcher at a fermentation science company here in Oslo that’s reimagining a new world of materials, more sustainable materials of everyday products. So let me give you some examples. So one is biomaterials. So taking a fungus, we can literally grow new materials using agricultural residues to replace unsustainable products like Styrofoam or Rockwool that often end up in landfills or in pollution. So we can grow things like soundproofing panels or insulation to buildings, or we can make mushroom Frisbees, like the possibility is nearly endless. We can also make textiles from fungi. So, for example, animal-free leathers. So normally, I mean, usually you have a cow, and it takes about three years to make a leather and all the resources and animal death that is involved. Not a great way to make leather if you can make it another way, like with fungi. It takes days to make it using fungi. Excuse me. Much better way that’s both efficient and ethical and how we can make leathers in the future. And then there’s food, a subject I’m particularly passionate about. Now, with fungi, we can make a whole range of sustainable and delicious foods from fungi, things like meat replacements for seafood, or dairy, for example, or even a new class of food that doesn’t look like any of that stuff. Possibilities are unlimited. And we can do it in a way that is a fraction of the environment footprint. Now, fungi are self-replicating organisms, so we can make it in really huge quantities and help address the challenge of how we’re going to make more food and lower our impact on the planet. It’s a big challenge. We can do it with fungi. And last but not least, fish feed. I mean, here we are in Norway, right? The world's largest producer of salmon. And what do we feed that salmon as proteins? Two things primarily: soy and fishmeal, neither of which are sustainable sources of protein for the future, because they contribute to overfishing in the oceans and land use patterns that degrade forests and other lands. So we need to come up with more sustainable sources in how we feed our fish. And what if we could do it using fungi to create the proteins to feed those fish? And we could do it in a way that we were using byproducts of food industries as food for our fungus when we grew it. It would be an amazingly sustainable system. And dare I say it, would help in our self-sufficiency. Now, one of the coolest things about being a fungal researcher is, with all that diversity out there, probably the coolest thing that fungi can do, we haven’t even uncovered yet. The most amazing fungal discoveries are still waiting to be made. And we’re only scratching the surface of what we might be able to achieve with the help of fungi. So I have a hope. And my hope is that we transfer our fungal problems into fungal solutions, that we look to the fungal world for new mindsets and new metaphors and even new materials as we think more collaboratively, regeneratively, and with more biointelligence as we approach the future. Just like fungi. Thank you very much. (Applause)

Related talks

Paul Stamets: 6 ways mushrooms can save the world

E.O. Wilson: My wish: Build the Encyclopedia of Life

Jae Rhim Lee: My mushroom burial suit

John C. Moore and Eric Berlow: Dead stuff: The secret ingredient in our food chain

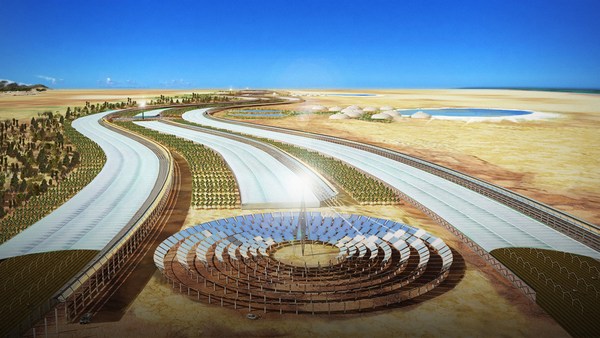

Michael Pawlyn: Using nature's genius in architecture