I call myself an “apocalyptic optimist,” but I wasn't always this way. I used to believe that technology could save us from the climate crisis, that all the big brains in the world would come up with a silver bullet to stop carbon pollution, that a clever policy would help that technology spread, and our concern about the greenhouse gases heating the planet would be a thing of the past, and we wouldn't have to worry about the polar bears anymore.

But time and time again, I saw that climate policy and business response were absolutely insufficient. Our big wins have been only small steps in the right direction. Even with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the US is nowhere near meeting its commitments under the Paris Agreement, and the US is not alone. In fact, the US is the number one producer of oil and natural gas in the world right now.

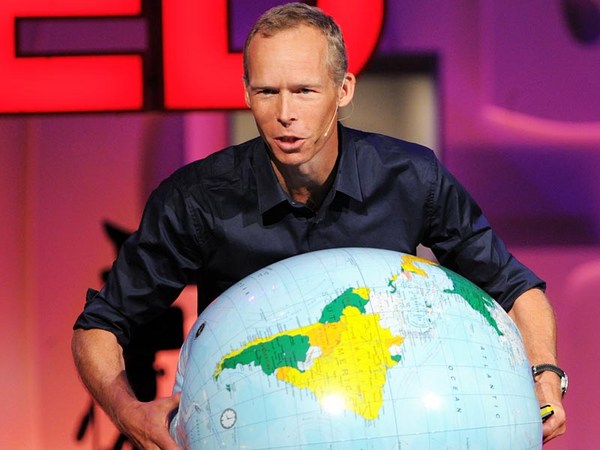

I'm a sociologist. I study anthro shifts, the process of monumental social change in a warming world. My work is part of the literature that documents why governments and businesses are failing to address the climate crisis effectively.

One of the main reasons is that fossil fuel interests have a stranglehold on decision making. Because of their access to resources and power, they have blocked systemic changes that are needed, promoting instead incremental policies and even climate denial.

It's time for us to face reality, and it's a bitter pill. The question isn't will climate change affect us. It's how many lives will be lost to the growing climate crisis? I still believe we can save ourselves from this crisis that humans created, though not all of us equally. Unfortunately, the mountains of data I've collected from policymakers, business representatives and activists show that saving ourselves is only possible with a mass mobilization of civil society that's driven by the pain and suffering of climate shocks around the world. These shocks come in the form of heat waves, droughts, fires and floods. As climate shocks come more frequently and hit with more severity, they will lead to additional social conflict as areas become uninhabitable, resource scarcity grows and people move to avoid the effects of climate change. So that's the apocalyptic part.

But here's where the optimism comes in. As our world warms and more people experience the effects of the climate crisis firsthand, there's evidence that climate shocks and the conflicts they motivate will get people out in the street demanding action. Civil society will build political pressure to force governments and businesses to shift away from fossil fuels. We're already seeing glimpses of this process in action. In 2023, I surveyed participants to the March to End Fossil Fuels in New York City. Over 75 percent of the 75,000 or so activists who participated reported personally experiencing the effects of climate change. This summer, my research found that 79 percent of participants in the Summer of Heat campaign to stop fossil fuel expansion had experienced climate shocks in the past six months. These activists engaged in non-violent civil disobedience, like singing and chanting and blocking buildings dressed as orcas and even hot dogs -- yep, hot dogs -- to send a message to big banks like Citibank and convince them to stop funding fossil fuel projects.

It’s time for us to all be apocalyptic optimists: prepared for the shocks that are coming and ready to rally as activists, disruptors and bridge builders. Together, we can pressure the state and the market to adopt the changes that our communities require to survive. Here's my advice about how to be the change makers we need.

First, activism and engagement must create community and solidarity. This is how we get over that necessary threshold and mobilize the masses. I've studied countless social movements, and the most effective and durable ones are those that bring people together across a diversity of identities and orientations. One of the reasons that the first Women's March in 2017 was the largest single day of protest in US history, is because its message resonated with people on an individual personal level. Although it was a women's march and the majority of participants reported turning out to show support for women's rights, people of color came out because they were also concerned about racial justice, and Latino participants joined because they were also worried about immigration policy under the first Trump administration. To date, the climate movement does not do a great job of connecting activists across identities, orientations or social classes. But it needs to.

Second, disruption, repression and even violence can help jolt sympathizers to take action. The type of activism that I'm talking about is not going to be peaceful, not because the activists are likely to get violent, but because those in power often do. Already, activists in Europe, the UK and the United States are being threatened and criminalized, with many facing jail time for blocking traffic, for organizing sit-ins or for throwing soup or smearing paint on the protective covering of artwork. It's much harder for activists in the developing world. Almost 200 environmental defenders are murdered each year because of their activism. Research shows that social movements get more confrontational as their struggles continue. This so-called “radical flank” involves tactics like blocking streets and occupying public spaces. Although these tactics are super unpopular, they are a necessary component of social movements as they expand and build capacity for social change by channeling sympathetic individuals into more moderate components of the movement. This process is what we call the “radical flank effect,” even though the tactics are frequently not particularly radical. Sympathizers are also mobilized to participate by witnessing violence against peaceful protesters. During the US civil rights movement, watching violence against activists motivated members of the broader population to join the movement. In 2020, when activists protesting the murder of George Floyd in Washington, DC, near the White House were tear-gassed, the crowds that turned out the following day were much larger.

Third, you don't have to be an activist to make a difference. We don't all need to get arrested protesting, but we must all work together to make our communities more resilient in the face of climate shocks. As the climate movement builds and grows and builds capacity, the climate crisis rages on. If we work to cultivate resilience in our communities, we can help to limit the human suffering that will come as the world warms. To be more resilient and to recover more quickly from the effects of climate change, service corps programs are popping up across the United States. When Hurricane Maria devastated the island of Puerto Rico in 2017, AmeriCorps deployed its members to help with disaster response, rebuilding and reconnecting food delivery to communities across the island. Similar programs are currently underway in mountain communities and others affected by hurricane Helene and hurricane Milton. This type of program is also popping up across Europe and Africa to build resilience. They support young people as well as older adults, training them to weatherize homes, install rooftop solar, remove debris from forested areas and to build more dense civic networks to support communities when disaster hits. These programs are much more effective when they connect people where they live, work and experience climate shocks. Because so much more is possible when we already know one another. Rather than parachuting in strangers during times of crisis.

As unfair as it may seem, the future is up to us. These times will not be easy or pain-free. But unless we get realistic about the path that we are on, too many of us will be caught off guard.

Some days it's hard to be an apocalyptic optimist. More climate records are broken. Extreme weather hits. Or another round of climate negotiations takes place and ends in a petrostate, with no measurable effects whatsoever on the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. But then I see communities pushing back. They vote to phase out natural gas and local buildings. They pressure banks to stop investing in fossil fuel infrastructure, or they work with their friends and neighbors to muck and gut buildings destroyed by flood or fire. As I witness these local people investing their time and energy in building communities that are more capable of withstanding the shocks that are yet to come, I'm optimistic once again.

Thank you.

(Applause)