I'd like to talk today about how we can change our brains and our society.

Meet Joe. Joe's 32 years old and a murderer. I met Joe 13 years ago on the lifer wing at Wormwood Scrubs high-security prison in London. I'd like you to imagine this place. It looks and feels like it sounds: Wormwood Scrubs. Built at the end of the Victorian Era by the inmates themselves, it is where England's most dangerous prisoners are kept. These individuals have committed acts of unspeakable evil. And I was there to study their brains. I was part of a team of researchers from University College London, on a grant from the U.K. department of health. My task was to study a group of inmates who had been clinically diagnosed as psychopaths. That meant they were the most callous and the most aggressive of the entire prison population. What lay at the root of their behavior? Was there a neurological cause for their condition? And if there was a neurological cause, could we find a cure?

So I'd like to speak about change, and especially about emotional change. Growing up, I was always intrigued by how people change. My mother, a clinical psychotherapist, would occasionally see patients at home in the evening. She would shut the door to the living room, and I imagined magical things happened in that room. At the age of five or six I would creep up in my pajamas and sit outside with my ear glued to the door. On more than one occasion, I fell asleep and they had to push me out of the way at the end of the session.

And I suppose that's how I found myself walking into the secure interview room on my first day at Wormwood Scrubs. Joe sat across a steel table and greeted me with this blank expression. The prison warden, looking equally indifferent, said, "Any trouble, just press the red buzzer, and we'll be around as soon as we can." (Laughter)

I sat down. The heavy metal door slammed shut behind me. I looked up at the red buzzer far behind Joe on the opposite wall. (Laughter)

I looked at Joe. Perhaps detecting my concern, he leaned forward, and said, as reassuringly as he could, "Ah, don't worry about the buzzer, it doesn't work anyway." (Laughter)

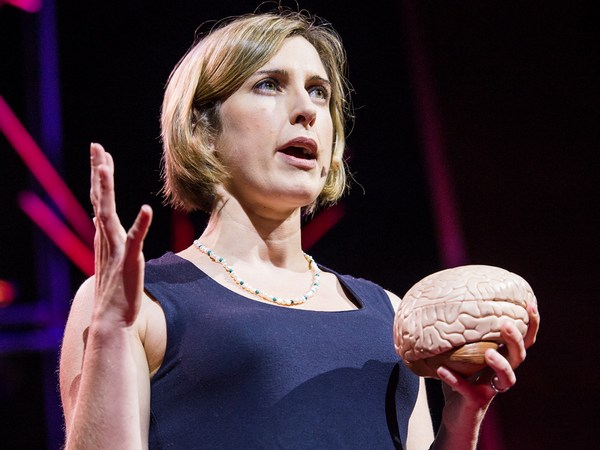

Over the subsequent months, we tested Joe and his fellow inmates, looking specifically at their ability to categorize different images of emotion. And we looked at their physical response to those emotions. So, for example, when most of us look at a picture like this of somebody looking sad, we instantly have a slight, measurable physical response: increased heart rate, sweating of the skin. Whilst the psychopaths in our study were able to describe the pictures accurately, they failed to show the emotions required. They failed to show a physical response. It was as though they knew the words but not the music of empathy. So we wanted to look closer at this to use MRI to image their brains. That turned out to be not such an easy task. Imagine transporting a collection of clinical psychopaths across central London in shackles and handcuffs in rush hour, and in order to place each of them in an MRI scanner, you have to remove all metal objects, including shackles and handcuffs, and, as I learned, all body piercings.

After some time, however, we had a tentative answer. These individuals were not just the victims of a troubled childhood. There was something else. People like Joe have a deficit in a brain area called the amygdala. The amygdala is an almond-shaped organ deep within each of the hemispheres of the brain. It is thought to be key to the experience of empathy. Normally, the more empathic a person is, the larger and more active their amygdala is. Our population of inmates had a deficient amygdala, which likely led to their lack of empathy and to their immoral behavior.

So let's take a step back. Normally, acquiring moral behavior is simply part of growing up, like learning to speak. At the age of six months, virtually every one of us is able to differentiate between animate and inanimate objects. At the age of 12 months, most children are able to imitate the purposeful actions of others. So for example, your mother raises her hands to stretch, and you imitate her behavior. At first, this isn't perfect. I remember my cousin Sasha, two years old at the time, looking through a picture book and licking one finger and flicking the page with the other hand, licking one finger and flicking the page with the other hand. (Laughter) Bit by bit, we build the foundations of the social brain so that by the time we're three, four years old, most children, not all, have acquired the ability to understand the intentions of others, another prerequisite for empathy. The fact that this developmental progression is universal, irrespective of where you live in the world or which culture you inhabit, strongly suggests that the foundations of moral behavior are inborn. If you doubt this, try, as I've done, to renege on a promise you've made to a four-year-old. You will find that the mind of a four-year old is not naïve in the slightest. It is more akin to a Swiss army knife with fixed mental modules finely honed during development and a sharp sense of fairness. The early years are crucial. There seems to be a window of opportunity, after which mastering moral questions becomes more difficult, like adults learning a foreign language. That's not to say it's impossible. A recent, wonderful study from Stanford University showed that people who have played a virtual reality game in which they took on the role of a good and helpful superhero actually became more caring and helpful towards others afterwards. Now I'm not suggesting we endow criminals with superpowers, but I am suggesting that we need to find ways to get Joe and people like him to change their brains and their behavior, for their benefit and for the benefit of the rest of us.

So can brains change? For over 100 years, neuroanatomists and later neuroscientists held the view that after initial development in childhood, no new brain cells could grow in the adult human brain. The brain could only change within certain set limits. That was the dogma. But then, in the 1990s, studies starting showing, following the lead of Elizabeth Gould at Princeton and others, studies started showing the evidence of neurogenesis, the birth of new brain cells in the adult mammalian brain, first in the olfactory bulb, which is responsible for our sense of smell, then in the hippocampus involving short-term memory, and finally in the amygdala itself. In order to understand how this process works, I left the psychopaths and joined a lab in Oxford specializing in learning and development. Instead of psychopaths, I studied mice, because the same pattern of brain responses appears across many different species of social animals. So if you rear a mouse in a standard cage, a shoebox, essentially, with cotton wool, alone and without much stimulation, not only does it not thrive, but it will often develop strange, repetitive behaviors. This naturally sociable animal will lose its ability to bond with other mice, even becoming aggressive when introduced to them. However, mice reared in what we called an enriched environment, a large habitation with other mice with wheels and ladders and areas to explore, demonstrate neurogenesis, the birth of new brain cells, and as we showed, they also perform better on a range of learning and memory tasks. Now, they don't develop morality to the point of carrying the shopping bags of little old mice across the street, but their improved environment results in healthy, sociable behavior. Mice reared in a standard cage, by contrast, not dissimilar, you might say, from a prison cell, have dramatically lower levels of new neurons in the brain.

It is now clear that the amygdala of mammals, including primates like us, can show neurogenesis. In some areas of the brain, more than 20 percent of cells are newly formed. We're just beginning to understand what exact function these cells have, but what it implies is that the brain is capable of extraordinary change way into adulthood. However, our brains are also exquisitely sensitive to stress in our environment. Stress hormones, glucocorticoids, released by the brain, suppress the growth of these new cells. The more stress, the less brain development, which in turn causes less adaptability and causes higher stress levels. This is the interplay between nature and nurture in real time in front of our eyes. When you think about it, it is ironic that our current solution for people with stressed amygdalae is to place them in an environment that actually inhibits any chance of further growth. Of course, imprisonment is a necessary part of the criminal justice system and of protecting society. Our research does not suggest that criminals should submit their MRI scans as evidence in court and get off the hook because they've got a faulty amygdala. The evidence is actually the other way. Because our brains are capable of change, we need to take responsibility for our actions, and they need to take responsibility for their rehabilitation. One way such rehabilitation might work is through restorative justice programs. Here victims, if they choose to participate, and perpetrators meet face to face in safe, structured encounters, and the perpetrator is encouraged to take responsibility for their actions, and the victim plays an active role in the process. In such a setting, the perpetrator can see, perhaps for the first time, the victim as a real person with thoughts and feelings and a genuine emotional response. This stimulates the amygdala and may be a more effective rehabilitative practice than simple incarceration. Such programs won't work for everyone, but for many, it could be a way to break the frozen sea within.

So what can we do now? How can we apply this knowledge? I'd like to leave you with three lessons that I learned. The first thing that I learned was that we need to change our mindset. Since Wormwood Scrubs was built 130 years ago, society has advanced in virtually every aspect, in the way we run our schools, our hospitals. Yet the moment we speak about prisons, it's as though we're back in Dickensian times, if not medieval times. For too long, I believe, we've allowed ourselves to be persuaded of the false notion that human nature cannot change, and as a society, it's costing us dearly. We know that the brain is capable of extraordinary change, and the best way to achieve that, even in adults, is to change and modulate our environment.

The second thing I have learned is that we need to create an alliance of people who believe that science is integral to bringing about social change. It's easy enough for a neuroscientist to place a high-security inmate in an MRI scanner. Well actually, that turns out not to be so easy, but ultimately what we want to show is whether we're able to reduce the reoffending rates. In order to answer complex questions like that, we need people of different backgrounds -- lab-based scientists and clinicians, social workers and policy makers, philanthropists and human rights activists — to work together.

Finally, I believe we need to change our own amygdalae, because this issue goes to the heart not just of who Joe is, but who we are. We need to change our view of Joe as someone wholly irredeemable, because if we see Joe as wholly irredeemable, how is he going to see himself as any different? In another decade, Joe will be released from Wormwood Scrubs. Will he be among the 70 percent of inmates who end up reoffending and returning to the prison system? Wouldn't it be better if, while serving his sentence, Joe was able to train his amygdala, which would stimulate the growth of new brain cells and connections, so that he will be able to face the world once he gets released? Surely, that would be in the interest of all of us.

(Applause) Thank you. (Applause)