Since humanity's earliest days, we’ve been plagued by countless disease-causing pathogens. Invisible and persistent, these microorganisms and the illnesses they incur have killed more humans than anything else in history. But which disease is deadliest varies across time and place. Because while the march of progress has made us safer from some infectious threats, human innovation often exposes us to surprising new maladies.

Our tour of history’s deadliest diseases begins when humans lived in small hunter-gatherer communities. The illnesses these pre-agricultural nomads encountered most likely came from the various animals they ate, and the soil and water they interacted with. There are no written records to help us identify these diseases, however, some illnesses leave distinct growths or lesions on the skeleton, allowing bioarchaeologists to diagnose ancient remains. And researchers have found that bones from this era suggest the presence of tuberculosis and treponemal infections.

While these conditions are life-threatening, the deadliest diseases are invariably part of widespread epidemics, and there’s no evidence of any large-scale outbreaks in this lengthy pre-agricultural period. However, when humans started developing agriculture around 12,000 years ago, it brought a whole new crop of diseases. Early farmers knew little about waste and water management, setting the stage for diarrheal diseases like dysentery. Much worse, the proliferation of open fields and irrigation created standing pools of water which brought mosquitoes and in turn malaria— one of history’s oldest and deadliest diseases. We don’t know exactly how many early farmers malaria killed, or how many it left vulnerable to other lethal infections. But we do know this mosquito-borne illness continued to spread through humanity’s next major development: urbanization.

In small communities, infectious diseases like measles and smallpox can only circulate so long before running out of hosts. But in densely populated regions with high birth rates, fast-evolving viruses like the flu can continually infect new individuals and morph into various strains. When large settlements became common, medical science hadn't advanced enough to effectively treat or even distinguish these variants. Nor was it prepared to deal with one of the deadliest pandemics of all time: the Black Death. From the 1330s to the 1350s, the bubonic plague swept Asia, Africa and Europe, reducing the global population from 475 million to roughly 350 million. Like most Afro-Eurasian diseases, the plague didn’t cross the Atlantic until Europeans did in the late 1400s. But at the height of the plague in Europe, Asia, and North Africa, infection was almost guaranteed, and the plague’s fatality rate ranged from 30 to 75%. However, the illness wasn't equally distributed among the population. Many wealthy lords and landowners were able to stay safe by hiding away in their spacious homes.

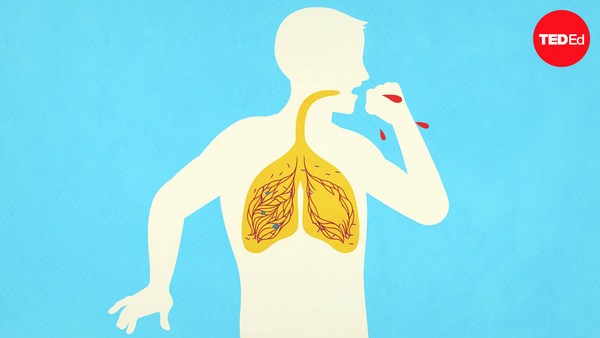

As medical knowledge became more robust, this kind of class disparity began reflecting who had access to medical care. And that divide became particularly apparent during the reign of our next deadly disease. By the beginning of the 19th century, tuberculosis was already one of the most common causes of death in Europe and the Americas. But the Industrial Revolution led to working and living conditions that were overcrowded and poorly ventilated, turning TB into an epidemic that killed a quarter of Europe’s adult population. The unhealthiest environments were largely populated by impoverished individuals who often went untreated, while doctors provided wealthier victims with the era’s most cutting-edge care.

Throughout the 20th century, vaccines became common in many countries, even eradicating the centuries-old viral threat of smallpox. The advent of vaccination, alongside improvements in nutrition and hygiene, have helped people live longer lives on average. And today, medical advances in rapid testing and mRNA vaccines can help us tackle new outbreaks in record time. However, countless regions around the world remain unable to access vaccines, leaving them vulnerable to older threats. Malaria still takes the lives of over 600,000 people every year, with 96% of deaths occurring in communities across Africa. Tuberculosis continues to infect millions, almost half of whom live in Southeast Asia. Addressing these ailments and those yet to emerge will require scientists to develop new and more effective medicines. But something governments and health care systems can do today is working to make the treatments we have already accessible to all.