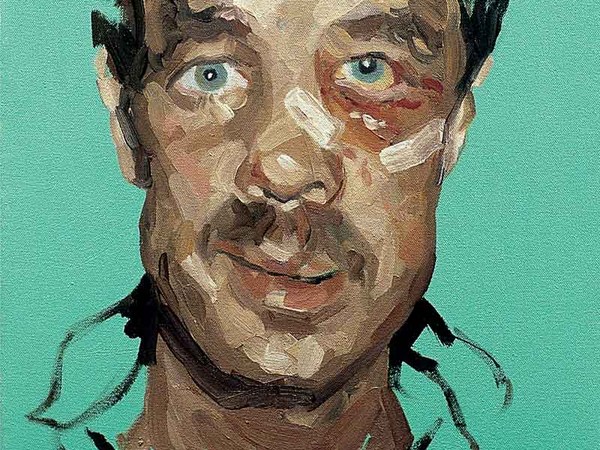

So, I was in the hospital for a long time. And a few years after I left, I went back, and the chairman of the burn department was very excited to see me -- said, "Dan, I have a fantastic new treatment for you." I was very excited. I walked with him to his office. And he explained to me that, when I shave, I have little black dots on the left side of my face where the hair is, but on the right side of my face I was badly burned so I have no hair, and this creates lack of symmetry. And what's the brilliant idea he had? He was going to tattoo little black dots on the right side of my face and make me look very symmetric.

It sounded interesting. He asked me to go and shave. Let me tell you, this was a strange way to shave, because I thought about it and I realized that the way I was shaving then would be the way I would shave for the rest of my life -- because I had to keep the width the same. When I got back to his office, I wasn't really sure. I said, "Can I see some evidence for this?" So he showed me some pictures of little cheeks with little black dots -- not very informative. I said, "What happens when I grow older and my hair becomes white? What would happen then?" "Oh, don't worry about it," he said. "We have lasers; we can whiten it out." But I was still concerned, so I said, "You know what, I'm not going to do it."

And then came one of the biggest guilt trips of my life. This is coming from a Jewish guy, all right, so that means a lot. (Laughter) And he said, "Dan, what's wrong with you? Do you enjoy looking non-symmetric? Do you have some kind of perverted pleasure from this? Do women feel pity for you and have sex with you more frequently?" None of those happened. And this was very surprising to me, because I've gone through many treatments -- there were many treatments I decided not to do -- and I never got this guilt trip to this extent. But I decided not to have this treatment. And I went to his deputy and asked him, "What was going on? Where was this guilt trip coming from?" And he explained that they have done this procedure on two patients already, and they need the third patient for a paper they were writing.

(Laughter)

Now you probably think that this guy's a schmuck. Right, that's what he seems like. But let me give you a different perspective on the same story. A few years ago, I was running some of my own experiments in the lab. And when we run experiments, we usually hope that one group will behave differently than another. So we had one group that I hoped their performance would be very high, another group that I thought their performance would be very low, and when I got the results, that's what we got -- I was very happy -- aside from one person. There was one person in the group that was supposed to have very high performance that was actually performing terribly. And he pulled the whole mean down, destroying my statistical significance of the test.

So I looked carefully at this guy. He was 20-some years older than anybody else in the sample. And I remembered that the old and drunken guy came one day to the lab wanting to make some easy cash and this was the guy. "Fantastic!" I thought. "Let's throw him out. Who would ever include a drunken guy in a sample?"

But a couple of days later, we thought about it with my students, and we said, "What would have happened if this drunken guy was not in that condition? What would have happened if he was in the other group? Would we have thrown him out then?" We probably wouldn't have looked at the data at all, and if we did look at the data, we'd probably have said, "Fantastic! What a smart guy who is performing this low," because he would have pulled the mean of the group lower, giving us even stronger statistical results than we could. So we decided not to throw the guy out and to rerun the experiment.

But you know, these stories, and lots of other experiments that we've done on conflicts of interest, basically kind of bring two points to the foreground for me. The first one is that in life we encounter many people who, in some way or another, try to tattoo our faces. They just have the incentives that get them to be blinded to reality and give us advice that is inherently biased. And I'm sure that it's something that we all recognize, and we see that it happens. Maybe we don't recognize it every time, but we understand that it happens.

The most difficult thing, of course, is to recognize that sometimes we too are blinded by our own incentives. And that's a much, much more difficult lesson to take into account. Because we don't see how conflicts of interest work on us. When I was doing these experiments, in my mind, I was helping science. I was eliminating the data to get the true pattern of the data to shine through. I wasn't doing something bad. In my mind, I was actually a knight trying to help science move along. But this was not the case. I was actually interfering with the process with lots of good intentions. And I think the real challenge is to figure out where are the cases in our lives where conflicts of interest work on us, and try not to trust our own intuition to overcome it, but to try to do things that prevent us from falling prey to these behaviors, because we can create lots of undesirable circumstances.

I do want to leave you with one positive thought. I mean, this is all very depressing, right -- people have conflicts of interest, we don't see it, and so on. The positive perspective, I think, of all of this is that, if we do understand when we go wrong, if we understand the deep mechanisms of why we fail and where we fail, we can actually hope to fix things. And that, I think, is the hope. Thank you very much.

(Applause)