I'm going to tell you a true story, but instead of the name of the protagonist, think about your favorite artist. Think about your favorite musician, and think about your favorite song by that musician. Think about them bringing that song from nothing to something into your ears and bringing you so much joy.

Now think about your favorite musician getting sued, and that lawyer saying, "I represent this group. I think you heard their song and then you wrote yours. You violated their copyright."

And imagine your musician saying, "No, it's not true. I don't think I've ever heard that song. But even if I did, I certainly wasn't thinking about them when I made my song."

Imagine the case going to trial and a judge saying, "I believe you, I don't think you consciously copied that group. But what I think did happen is you subconsciously copied them. You violated the copyright, and you have to pay them a lot of money.”

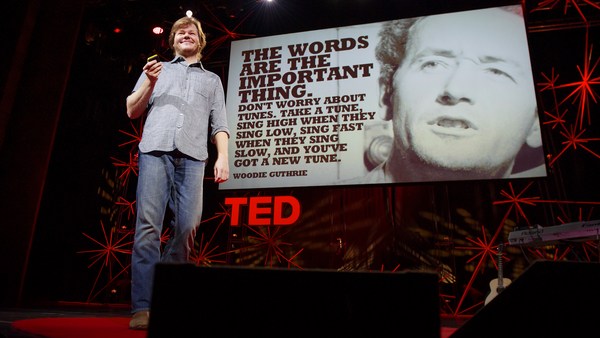

Think about whether that's fair or just. This actually happened to George Harrison, the lead guitarist of The Beatles, and the group was The Chiffons, who's had a song "He's so fine, oh so fine." And George Harrison had a song, "My sweet Lord, oh, sweet Lord." But what neither George Harrison nor The Chiffons nor the judge, really, nor anybody else had considered, is maybe since the beginning of time, the number of melodies is remarkably finite. Maybe there are only so many melodies in this world. And The Chiffons, when they picked their melody, plucked it from that already existing finite melodic data set. And George Harrison happened to have plucked the same melody from that same finite melodic data set.

This is a different way of thinking about music in a way that judges and lawyers nor musicians have thought about. Because when those groups have thought about musicians, they think about them drawing from their own creative wellspring, bringing from nothing, something into the world. They have a blank page upon which they can put their creativity. That's actually not true. As George Harrison realized, you have to avoid every song that's ever been written, because if you don't, you get sued. If you're lucky, you pluck one of those already existing melodies that hasn't been taken. If you're unlucky, you pluck a melody that's already been taken. Whether you've heard that song or not, maybe you've never heard it before. If that happens, if you're lucky, you have a co-songwriter or somebody who says, that new song sounds a lot like that old song. And you change it before it goes out the door. Now, if you're unlucky, you don't have somebody telling you that, you release it out in the world, the group hears your song and they sue you for a song maybe that you've never heard before in your life. You've just stepped on a melodic landmine.

The thing is, this is the world before my colleague, Noah Rubin, and I have started our project. The world now looks like this. We filled in every melody that's ever existed and ever can exist. Every step is going to be a melodic landmine. And ironically, this is actually trying to help songwriters. Let me tell you how.

I'm a lawyer. I've been a lawyer since 2002. I've litigated copyright cases, I've taught law school copyright cases. I'm also a musician. I have a bachelor’s degree in music, I’m a performer, I'm a recording artist, and I also produce records. I'm also a technologist. I've been coding since 1985, for the web since '95. I’ve done cybersecurity, and I also currently design software. So that puts me right in the middle of a Venn diagram that gives me a few insights that if I were in any one of those areas I might not have had. And my colleague Noah Rubin, in addition to being one of the smartest people I've ever known, he's also a musician, and he's also one of the most brilliant programmers I've known. And between our work, we came to a realization that you may have had saying, "You know that new song? It sounds a lot like this other old song." And there's a reason for that. We've discovered that there is only so many melodies, there are only so many notes that can be arranged in so many ways. And that's different than visual art, where they're an infinite number of brushstrokes, colors and subjects that to accidentally do them is very difficult. Similarly with language, the English language has 117,000 words in it, so the odds of accidentally writing the same paragraph are next to zero. In contrast, music doesn't have 117,000 words. Music has eight notes. Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, Do. One two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. And every popular melody that's ever existed and ever can exist is those eight notes.

Now, it's remarkably small. I worked in cybersecurity, and I know if I wanted to attack your password and hack your password, one way to do it is to use a computer to really quickly say aaaa. No? Aab, aac, And to keep running until it hits your password. That's called brute-forcing a password. So I thought, what if you could brute force melodies? What if you could say, Do-Do-Do-Do, Do-Do-Do-Re, Do-Do-Do-Mi. And then exhaust every melody that's ever been. And the way the computers read music is called MIDI. And in MIDI it looks like this Do-Do-Do-Do, Do-Do-Do-Re.

So I approached my colleague Noah, I said, Noah, can you write an algorithm to be able to march through every melody that's ever existed and ever can exist?

He said, "Yeah, I could do that."

So at a rate of 300,000 melodies per second, he wrote a program to write to disk every melody that's ever existed and ever can exist. And in my hand right now is every melody that's ever existed and ever can exist. And the thing is, to be copyrighted, you don't have to do anything formal. As soon as it's written to a fixed, tangible medium, this hard drive, it's copyrighted automatically.

Now, this leaves copyright law with a very interesting question, because you think about the world before and songwriters had to avoid every song that's ever been written, in red. Noah and I have exhausted the entire melodic copyright. So if you superimpose the songs that have been written, in red, with the songs that haven't yet been written, you have an interesting question: Have we infringed every melody that's ever been? And in the future, every songwriter that writes in the green spots, have they infringed us?

Now, you might think at this point, are you some sort of copyright troll that's trying to take over the world? And I would say, no, absolutely not. In fact, the opposite is true. Noah and I are songwriters ourselves. We want to make the world better for songwriters. So what we've done is we're taking everything and putting it in the public domain. We're trying to keep space open for songwriters to be able to make music. And we're not focused on the lyrics, we're not focused on recording, we're focused on melodies. And the thing is, we're running out of melodies that we can use. The copyright system is broken and it needs updating.

Some of the insights that we've received as part of our work is that melodies to a computer are just numbers because those melodies have existed since the beginning of time, and we're only just discovering them. So the melody Do-Re-Mi-Re-Do to a computer is literally 1-2-3-2-1. So really the number 1-2-3-2-1 is just a number. It's just math that's been existing since the beginning of time. And under the copyright laws, numbers are facts. And under copyright law, facts either have thin copyright, almost no copyright or no copyright at all. So maybe if these numbers have existed since the beginning of time where we're just plucking them out, maybe melodies are just math, which is just facts, which maybe are not copyrightable. Maybe if somebody's suing over a melody alone, not lyrics, not recordings, but just the melody alone, maybe those cases go away. Maybe they get dismissed.

Now you might say, well, what constitutes a melody? And we were initially going to take the entire piano keyboard and be able to do the entire keyboard. But we thought, let's focus on the vocal range, which is actually two octaves. And then we thought, no, actually we're thinking about pop music, which is the only thing that makes money that people sue over. So we looked at musicologists, and they have debated what is a motif, a short melody versus a longer melody. And we landed with 12 notes. And then we superimposed that number with songs that have either been litigated or threatened to be litigated. For example, The Chiffons had “He’s so fine, oh so fine.” Versus “My sweet Lord, Oh, sweet Lord.” Eight notes.

Doo doo doo doo doo doo doo. (Laughter) Doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo. That's so close.

(Laughter)

"Oh, I won't back down. No, I won't back down." Versus “Won’t you stay with me 'cause you're all I need." Ten notes.

Doo doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo. Versus Katy Perry's Doo doo doo doo, doo doo doo, doo. Last two notes are different. The jury didn't care, 2.8 million dollars.

Audience: Ooh.

DR: So every song within that is within our parameters of eight notes up, major and minor, 12 notes across. So what you see in red is every popular melody that's ever existed and ever can exist. So all Noah and I had to do is to be able to exhaust that remarkably finite, remarkably small data set. There aren't that many of them. Eight up, 12 across.

You might say, Damien, songs are more than just melodies, there's chords too. And I would totally agree with you because it turns out that that's even easier. In 2017, Peter Burkimsher exhausted every chord. You can download it today in GitHub. We're instead focused not on lyrics, not on recordings, we're focused on melodies. And the thing is, we're running out because the song isn't just a single melody, but there are many parts to a song, and each part of that song can have many motifs and melodies within it. So each song can have up to ten melodies and motifs. So SoundCloud, which is a way that musicians can upload to this website and distribute their work, SoundCloud currently has 200 million songs, and the number of open spaces is shrinking exponentially. Because every basement musician is recording, and they’re recording and they’re uploading it to YouTube, to Spotify and to SoundCloud. And they are exhausting the entire mathematical data set. They're exhausting the open spaces. until there are not going to be any more left. What Noah and I have done is we're trying to preserve those spots that are left. We're trying to be able to take those green spots, put them in the public domain so that other people can be able to make them. Because we're running out.

The thing is we're just getting started because if you go to our website, AllTheMusic.info, you can not only download all the music we've made, which is a lot, you can also download the program that we used, and we're giving away the code for free so you can expand upon our work. Something I didn't tell you is that those eight notes that we did, as we speak right now, we've expanded that to 12 notes. So instead of just the white notes, now we've got the black notes, too. So we're covering jazz, classical music, and we think it's only a matter of time before somebody is going to expand that to do the entire piano keyboard and take our 12 notes and expand it to 100 with every rhythmic variation and every chordal variation till our remarkably finite mathematical data set gets further exhausted.

This is going to happen. And the thing is, how is the law going to respond? Because the thing is, we're not focused on somebody copying a previous person's melody. We're focused instead on somebody accidentally copying a song that they either have heard and forgotten about or have never heard before in their lives. And the chance of landing in an open spot is remarkably small, and it's shrinking every day. And the thing is, the odds of you as a songwriter getting sued are remarkably high. And if you get sued, you're going want to think about what a judge or a jury is going to think about, and they are going to think about two questions. The first question is: Is that previous songwriter’s copyright valid? Do they even have a copyright in that previous song? Second question is: Did you infringe their copyright? So to the first question, maybe the answer to that is no, because if they're suing just over the melody, maybe that melody's existed since the beginning of time. Maybe there are only so many notes that are math, that are not copyrightable. To the second question did you infringe, there are two sub questions. The first question is: Did you access, did you hear that previous song? And if so, are those two songs substantially similar? Now the first question: Did you access or hear that previous song? That's got a lot of problems, it's really problematic. And the reason for that is there are only a few cases where access is crystal clear. For example, John Fogerty was alleged to have infringed John Fogerty when he was part of Creedence. So clearly John Fogerty had access to John Fogerty songs. On the opposite end of the spectrum, on no access, what if a baby were to sing into their toy? And again, as soon as the toy recorder happens, it's copyrighted automatically, it's a fixed, tangible medium. So if a baby starts singing Da da da da da, da da da da da da. And a year later, Taylor Swift sings, "I stay up too late. Got nothing in my brain." Clearly, Taylor Swift has not infringed that baby because Taylor Swift has not heard that baby's recording, OK? Clear case of no access.

But the thing is, almost none of the cases are that clear. What if there's a question mark as to whether the second person heard it or not? Maybe they heard it, maybe they didn't. Maybe they heard it and forgot it. Maybe they subconsciously infringed. These are all what the law calls fact questions. And the thing is, almost every copyright case that comes out is a fact question. Almost never is it as clear as John Fogerty or as clear as Taylor Swift. Almost every case is that middle section, that fact question. And the hard part about fact questions is they're notoriously hard to resolve at an early stage in the case, because when you think about a life span of a lawsuit, it starts out as a cease and desist letter. You need to pay me or I'll sue you. It goes forward and it's going to take years. And the thing about fact questions, they don't get resolved until the end of that process. That's what happened to George Harrison. After trial, the judge said, "I think you subconsciously infringed."

So if you're a songwriter who's never heard a melody before, but you are approached by somebody saying you stole their song, what are you going to do? Sam Smith was approached by Tom Petty. Tom Petty said, “My song ‘Won’t Back Down’ sounds like your ‘Stay with Me.’” Sam Smith reportedly responded, "Hey, man, I've never heard your song before. That was written before I was born." But if I was in Sam Smith’s position, I would look at this long road ahead of me and the prospect at the end of a judge saying, you know, "I think you subliminally infringed." So what are you going to do? It's not surprising that Sam Smith made Tom Petty a co-songwriter, giving Tom Petty a lot of his songwriting royalties.

Radiohead had a song, "And I'm a creep. I'm a weirdo." The Hollies said, "Hey, that sounds like our song." They made them co-songwriters

Lana Del Rey ironically, had a song that sounds like "Creep." Offered to make them co-songwriters, reportedly.

Katy Perry had a song that she testified and all of her co-songwriters testified, "I have never heard that previous song before in my life" and the other side didn't dispute it. They say, "We have no evidence that they actually heard the song, but we did have three-point-some million YouTube views, so they must have heard it." A jury agreed with them and Katy Perry was on the hook for 2.8 million dollars.

Now, if you are an accused songwriter who's never heard the song before, that is an untenable position. How are you going to avoid getting shaken down for something that you may have never heard? Shouldn't there be an easier way? Shouldn't there be a way that early on in that process for a judge or a lawyer to be able to have an early evidentiary hearing to say maybe melodies are math, which are facts which are not copyrightable. Or maybe there's no evidence showing that this later person has heard the earlier person's song. Maybe the idea of subconscious infringement goes by.

Now if you are a songwriter, you should really care about this because each day you are walking in a minefield that you didn't even know was there. You’re trying to avoid every song, whether you’ve heard that song or not. And Noah and I, we're trying to preserve those open spaces so that you can be able to make the music in the public domain in a way that you've always thought it. The question is not: “Have I made this new song or not?” Because no song is new. Noah and I have exhausted the data set. The real question: "Is my song a green song, or is my song a red song?" Or perhaps the real question is: Should you have the blank page that everybody thinks is there in the first place?

If you're a judge or a lawyer, think about having an early evidentiary hearing to be able to take the evidenciary burden from the defendant to prove negative that they've never heard that song and bring it back to the plaintiff where it belongs, that they have to prove that the other side heard the song. And they have to prove that that melody is more than just a fact.

And if you are a song lover, you should really care about this because the current state has a chilling effect on songwriters. Something that I haven't told you is that George Harrison, after the trial, he stopped writing music for a while. He told "Rolling Stone" that, after the trial, "It's hard to start writing again because every song I hear sounds like something else." There's a reason for that, George. Because there are only so many notes. There are only so many melodies. And the open spaces are running out exponentially.

Now, ironically, Noah and I have made all the melodies and put them into the public domain in an effort to try to give songwriters more freedom, to be able to make more and more music and less fear of accidentally stepping on musical landmines. Noah and I have made all the music to be able to allow future songwriters to make all of their music.

Thank you.

(Applause)