This is your conference, and I think you have a right to know a little bit right now, in this transition period, about this guy who's going to be looking after it for you for a bit. So, I'm just going to grab a chair here.

Two years ago at TED, I think -- I've come to this conclusion -- I think I may have been suffering from a strange delusion. I think that I may have believed unconsciously, then, that I was kind of a business hero. I had this company that I'd spent 15 years building. It's called Future; it was a magazine publishing company. It had recently gone public and the market said that it was apparently worth two billion dollars, a number I didn't really understand. A magazine I'd recently launched called Business 2.0 was fatter than a telephone directory, busy pumping hot air into the bubble. (Laughter) And I was the 40 percent owner of a dotcom that was about to go public and no doubt be worth billions more. And all this had come from nothing. Fifteen years earlier, I was a science journalist who people just laughed at when I said, "I really would like to start my own computer magazine." And 15 years later, there are 100 of them and 2,000 people on staff and it was just such heady times. The date was February 2000. I thought the little graph of my business life that kind of looked a bit like Moore's Law -- ever upward and to the right -- it was going to go on forever. I mean, it had to. Right? I was in for quite a surprise.

The dotcom, ironically called Snowball, was the very last consumer web company to go public the next month before NASDAQ exploded, and I entered 18 months of business hell. I watched everything that I'd built crumbling, and it looked like all this stuff was going to die and 15 years work would have come for nothing. And it was gut wrenching. It took eight years of blood, sweat and tears to reach 350 employees, something which I was very proud of in the business. February 2001 -- in one day we laid off 350 people, and before the bloodshed was finished, 1,000 people had lost their jobs from my companies. I felt sick. I watched my own net worth falling by about a million dollars a day, every day, for 18 months. And worse than that, far worse than that, my sense of self-worth was kind of evaporating. I was going around with this big sign on my forehead: "LOSER." (Laughter) And I think what disgusts me more than anything, looking back, is how the hell did I let my personal happiness get so tied up with this business thing?

Well, in the end, we were able to save Future and Snowball, but I was, at that point, ready to move on. And to cut a long story short, here's where I came to. And the reason I'm telling this story is that I believe, from many conversations, that a lot of people in this room have been through a similar kind of rollercoaster -- emotional rollercoaster -- in the last couple years. This has been a big, big transition time, and I believe that this conference can play a big part for all of us in taking us forward to the next stage to whatever's next. The theme next year is re-birth.

It was at the same TED two years ago when Richard and I reached an agreement on the future of TED. And at about the same time, and I think partly because of that, I started doing something that I'd forgotten about in my business focus: I started to read again. And I discovered that while I'd been busy playing business games, there'd been this incredible revolution in so many areas of interest: cosmology to psychology to evolutionary psychology to anthropology to ... all this stuff had changed. And the way in which you could think about us as a species and us as a planet had just changed so much, and it was incredibly exciting. And what was really most exciting -- and I think Richard Wurman discovered this at least 20 years before I did -- was that all this stuff is connected. It's connected; it all hooks into each other.

We talk about this a lot, and I thought about trying to give an example of this. So, just one example: Madame de Gaulle, the wife of the French president, was famously asked once, "What do you most desire?" And she answered, "A penis." And when you think about it, it's very true: what we all most desire is a penis -- or "happiness" as we say in English. (Laughter) And something ... good luck with that one in the Japanese translation room. (Laughter) (Applause)

But something as basic as happiness, which 20 years ago would have been just something for discussion in the church or mosque or synagogue, today it turns out that there's dozens of TED-like questions that you can ask about it, which are really interesting. You can ask about what causes it biochemically: neuroscience, serotonin, all that stuff. You can ask what are the psychological causes of it: nature? Nurture? Current circumstance? Turns out that the research done on that is absolutely mind-blowing. You can view it as a computing problem, an artificial intelligence problem: do you need to incorporate some sort of analog of happiness into a computer brain to make it work properly? You can view it in sort of geopolitical terms and say, why is it that a billion people on this planet are so desperately needy that they have no possibility of happiness, and whereas almost all the rest of them, regardless of how much money they have -- whether it's two dollars a day or whatever -- are almost equally happy on average? Or you can view it as an evolutionary psychology kind of thing: did our genes invent this as a kind of trick to get us to behave in certain ways? The ant's brain, parasitized, to make us behave in certain ways so that our genes would propagate? Are we the victims of a mass delusion? And so on, and so on.

To understand even something as important to us as happiness, you kind of have to branch off in all these different directions, and there's nowhere that I've discovered -- other than TED -- where you can ask that many questions in that many different directions. And so, it's the profound thing that Richard talks about: to understand anything, you just need to understand the little bits; a little bit about everything that surrounds it. And so, gradually over these three days, you start off kind of trying to figure out, "Why am I listening to all this irrelevant stuff?" And at the end of the four days, your brain is humming and you feel energized, alive and excited, and it's because all these different bits have been put together. It's the total brain experience, we're going to ... it's the mental equivalent of the full body massage. (Laughter) Every mental organ addressed. It really is.

Enough of the theory, Chris. Tell us what you're actually going to do, all right? So, I will. Here's the vision for TED.

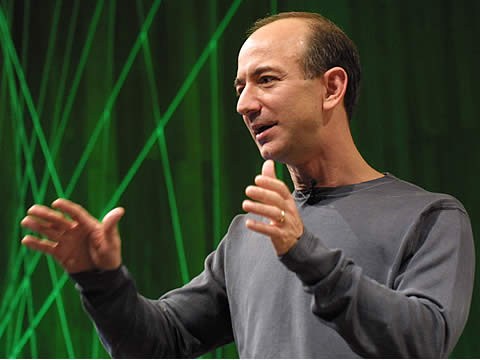

Number one: do nothing. This thing ain't broke, so I ain't gonna fix it. Jeff Bezos kindly remarked to me, "Chris, TED is a really great conference. You're going to have to fuck up really badly to make it bad." (Laughter) So, I gave myself the job title of TED Custodian for a reason, and I will promise you right here and now that the core values that make TED special are not going to be interfered with. Truth, curiosity, diversity, no selling, no corporate bullshit, no bandwagoning, no platforms. Just the pursuit of interest, wherever it lies, across all the disciplines that are represented here. That's not going to be changed at all.

Number two: I am going to put together an incredible line up of speakers for next year. The time scale on which TED operates is just fantastic after coming out of a magazine business with monthly deadlines. There's a year to do this, and already -- I hope to show you a bit later -- there's 25 or so terrific speakers signed up for next year. And I'm getting fantastic help from the community; this is just such a great community. And combined, our contacts reach pretty much everyone who's interesting in the country, if not the planet. It's true.

Number three: I do want to, if I can, find a way of extending the TED experience throughout the year a little bit. And one key way that we're going to do this is to introduce this book club. Books kind of saved me in the last couple years, and that's a gift that I would like to pass on. So, when you sign up for TED2003, every six weeks you'll get a care package with a book or two and a reason why they're linked to TED. They may well be by a TED speaker, and so we can get the conversation going during the year and come back next year having had the same intellectual, emotional journey. I think it will be great.

And then, fourthly: I want to mention the Sapling Foundation, which is the new owner of TED. What Sapling's ownership means is that all of the proceeds of TED will go towards the causes that Sapling stands for. And more important, I think, the ideas that are exhibited and realized here are ideas that the foundation can use, because there's fantastic synergy. Already, just in the last few days, we've had so many people talking about stuff that they care about, that they're passionate about, that can make a difference in the world, and the idea of getting this group of people together -- some of the causes that we believe in, the money that this conference can raise and the ideas -- I really believe that that combination will, over time, make a difference. I'm incredibly excited about that. In fact, I don't think, overall, that I've been as excited by anything ever in my life. I'm in this for the long run, and I would be greatly honored and excited if you'll come on this journey with me.