The contents of this metal cylinder could either revolutionize technology or be completely useless— it all depends on whether we can harness the strange physics of matter at very, very small scales. To have even a chance of doing so, we have to control the environment precisely: the thick tabletop and legs guard against vibrations from footsteps, nearby elevators, and opening or closing doors. The cylinder is a vacuum chamber, devoid of all the gases in air. Inside the vacuum chamber is a smaller, extremely cold compartment, reachable by tiny laser beams. Inside are ultra-sensitive particles that make up a quantum computer.

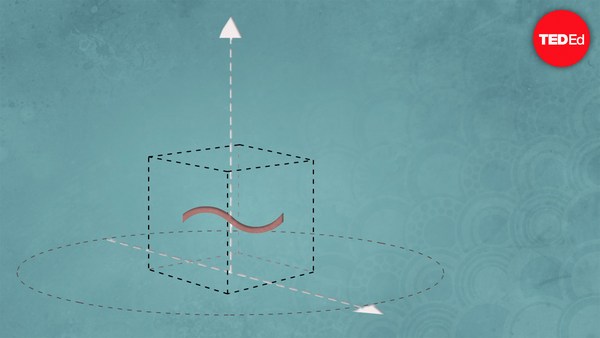

So what makes these particles worth the effort? In theory, quantum computers could outstrip the computational limits of classical computers. Classical computers process data in the form of bits. Each bit can switch between two states labeled zero and one. A quantum computer uses something called a qubit, which can switch between zero, one, and what’s called a superposition. While the qubit is in its superposition, it has a lot more information than one or zero. You can think of these positions as points on a sphere: the north and south poles of the sphere represent one and zero. A bit can only switch between these two poles, but when a qubit is in its superposition, it can be at any point on the sphere. We can’t locate it exactly— the moment we read it, the qubit resolves into a zero or a one. But even though we can’t observe the qubit in its superposition, we can manipulate it to perform particular operations while in this state.

So as a problem grows more complicated, a classical computer needs correspondingly more bits to solve it, while a quantum computer will theoretically be able to handle more and more complicated problems without requiring as many more qubits as a classical computer would need bits.

The unique properties of quantum computers result from the behavior of atomic and subatomic particles. These particles have quantum states, which correspond to the state of the qubit. Quantum states are incredibly fragile, easily destroyed by temperature and pressure fluctuations, stray electromagnetic fields, and collisions with nearby particles. That’s why quantum computers need such an elaborate set up. It’s also why, for now, the power of quantum computers remains largely theoretical. So far, we can only control a few qubits in the same place at the same time.

There are two key components involved in managing these fickle quantum states effectively: the types of particles a quantum computer uses, and how it manipulates those particles. For now, there are two leading approaches: trapped ions and superconducting qubits.

A trapped ion quantum computer uses ions as its particles and manipulates them with lasers. The ions are housed in a trap made of electrical fields. Inputs from the lasers tell the ions what operation to make by causing the qubit state to rotate on the sphere. To use a simplified example, the lasers could input the question: what are the prime factors of 15? In response, the ions may release photons— the state of the qubit determines whether the ion emits photons and how many photons it emits. An imaging system collects these photons and processes them to reveal the answer: 3 and 5.

Superconducting qubit quantum computers do the same thing in a different way: using a chip with electrical circuits instead of an ion trap. The states of each electrical circuit translate to the state of the qubit. They can be manipulated with electrical inputs in the form of microwaves. So: the qubits come from either ions or electrical circuits, acted on by either lasers or microwaves. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. Ions can be manipulated very precisely, and they last a long time, but as more ions are added to a trap, it becomes increasingly difficult to control each with precision. We can’t currently contain enough ions in a trap to make advanced computations, but one possible solution might be to connect many smaller traps that communicate with each other via photons rather than trying to create one big trap. Superconducting circuits, meanwhile, make operations much faster than trapped ions, and it’s easier to scale up the number of circuits in a computer than the number of ions. But the circuits are also more fragile, and have a shorter overall lifespan.

And as quantum computers advance, they will still be subject to the environmental constraints needed to preserve quantum states. But in spite of all these obstacles, we’ve already succeeded at making computations in a realm we can’t enter or even observe.