Hello there. Artificial intelligence is, of course, literally a new beginning. We are trying to create a new type of a thinking being. In fact, we have achieved a lot since we got started with this project. Computers can now play chess much better than humans. They can analyze radiological images better than human doctors. But today, I will talk about a domain where AI has not yet reached the level of a person of average IQ: understanding human language. You have probably read this horrific news item about the "chatbots" which are programmed to chat with people. In 2016, Microsoft created a Twitter AI character which was supposed to learn the nuances of human language by tweeting with people. Twenty-four hours later, they had to take it offline. Due to the nasty things, curses etc. that people wrote to it in their tweets, it turned into this nauseating character who said things like, "Hitler was so good." It does not exist any more. A year later, in China - maybe you have not heard about this one - a similar end was waiting for two chatbots which were launched in China to chit chat with users on Chinese social media sites after they started to talk about their dreams of moving to the States or mentioned their dislike for the Chinese Communist Party. They were deactivated for a few days after the incident. After they were reactivated, they started talking very "carefully" when those issues came up, giving answers like, "Sorry, I can not understand you." People who use the digital assistant Siri already know what a big engineering success it is. Yet there's more to the story: Authors and poets in every language are hired so that Siri can give proper answers in such situations. They are also writing scripts so that it doesn't have to confess it can't understand what is being said and it can continue the illusion of being intelligent by diverting the conversation when it gets stuck. Amazon also has a digital assistant named Alexa, which doesn't have a Turkish version yet. They promised a one-million-dollar prize to the programming team which will enable Alexa to chat with people for 20 minutes without causing extensive boredom. No one has been able to do that yet. The problem is that there are lots of very simple things that humans know, and computers don't. And we need to have a way of teaching them those things. Let me tell you a personal story about that. A long time ago, maybe 25 years or so, I bought a third-grade math textbook for primary school students and randomly picked 20 problems from it. Then I started to write a program which would "understand Turkish." It would understand these particular arithmetic problems in Turkish and solve them. I was thinking that I would therefore reach a new level in the computer understanding of the Turkish language and write another paper. The name of the program was ALİ, a Turkish acronym for "arithmetic language processor." It could solve problems like these: There were this many workers at a factory. That many of them were fired, and this many retired. How many were left? Or questions like, "That many students from College A and this many students from College B attended the ceremony. What's the total number of students?" requiring really simple arithmetic. You think that's easy peasy? Ask Siri the same questions, and see if it can solve them all. Let me tell you, it took two years of my youth, and I used to have gorgeous hair when I got started. (Laughter) Here is the problem. Let us go through this example. There were 67 liters of diesel in the gas tank of a truck. The driver bought 145 liters more. How much diesel does the truck have now? We are skipping the linguistics routines that analyze all this in Turkish. Let's come to the point where the AI can understand the fact that there need to be 212 liters at the end of the first two sentences. There, we come to a point where it knows that there are 212 liters of diesel in the gas tank, but what was the wording of the question again? "What's the sum of diesel in the truck?" "How much diesel does the truck have now?" ALİ could not answer that with the information we have mentioned. Do you see what the problem was? "The gas tank of the truck" is not the same thing as "the truck," and computers do not know automatically that if the tank contains something, the truck also contains that thing. And that's really complicated. "Ahmet's father had five kids" does not mean "Ahmet had five kids." On the other hand, when the gas tank of the truck has the petrol, the truck has it as well. That's why I had to specify in the program all this knowledge that people already inherently know. The technical name for this stuff is "commonsense knowledge." "The gas tank of the truck is a part of the truck." "If A is a part of B, right, B should contain everything contained in A." All of this information that I consider commonsense is all the things that I do not tell you while we are talking since I assume that you already know it all. We can not have a proper conversation with those chatbots since they know none of those things. After I coded all these, ALİ could solve all 20 problems properly. I had no more energy to go on to the 21st. Now, I'll tell you the story of a man who dedicated his life to this problem of coding commonsense knowledge: Douglas Lenat, a famous American computer scientist. This is him in the 1980s. He started a project called Cyc in 1982. And this is exactly what the project was about: To code all the commonsense knowledge that computers don't know. To write a million lines, if a million lines are needed. He founded a corporation where they do the following: If you are drinking coffee, the open side of the cup is facing upwards. The king is a man. Then his wife should be a woman, and she is called the queen. People can't go to work after they die. And so on. They are coding all the items of information which people already know and computers need to know in order to understand human language, one by one. And this is him today. After 35 years, the project is still in progress. I think there's an obvious problem here. It's clearly problematic to code manually. Now it's time to hear the good news. We have had a revolution in AI, and computers can now learn certain things on their own, without us having to code them manually. This is a machine-learning revolution. Linguists have the following idea: If two words are exact synonyms of each other, then the collections of all other words surrounding them in various sentences will also be similar to each other. Based on this idea, this man, who is proof of the fact that you don't need to be bald in order to be handsome if you're an AI researcher, named Tomas Mikolov, did the following while working for Google five years ago. Now think of all the documents in English at Google. The work I'll be telling you about was in English. Now imagine all the documents in English. For every word in every sentence, you're supposed to find out how many times it has appeared in the same sentence with any other words. For every imaginable pair of words, we have the computer count how many times these two words appear together in the same sentence or not. It's a computer, so it can do the computations anyway. The idea is that, if the two words are close to each other in meaning, the same words appear with similar frequencies in their surroundings. Let's say, we can easily see that both words "cat" and "dog" will appear frequently in the same sentences with the words "flea" or "rabies," "vaccine," "tail," "pet," and so on, but not with words like "printer," "generator" or "inflation." Do we see this? So, we can prepare a number sequence containing the frequencies of the neighboring words for every single word. Such a number sequence is called a "vector," as you might well know if they still teach it in high school. The computer can automatically position similar number sequences closer to each other, and the dissimilar ones far from each other on some sort of a map or space. What I mean is that the computer, which knows no English, creates a vector for each single word by doing the computations. Yet, the vector of "cat" is found in a location close to the vector of "dog" in that space for the reasons I just explained. Or the vector of the school Buffy the Vampire Slayer attends - they really looked at that - is positioned close to the vector of Hogwarts, where Harry Potter studies. Thus they are found to be positioned close to each other in terms of their meaning. There's more. As you will recall from that high school course, you can do arithmetic on these vectors. They can be added or subtracted, and you might say, "So what?" Mikolov discovered this. He did the following addition and subtraction operations on the vectors thus learned. He came up with the question, "What would happen if the king were a woman instead of a man" when he subtracted the word "man" from the word "king" and added the word "woman." Guess what the resulting vector is near to? "Queen." No one had hand-coded that equation as the Lenat team. The computer discovered it all by itself after counting millions of millions of words on the documents we created. I have more to tell you, and this really happened. There is info on Turkey there. If you take "France" out of "Paris" and add "Turkey" - yes, you got it right - it's Ankara. This means in this vector space, there's a direction which leads from the names of countries to the names of their capitals, which is really stunning. When you ask, What would Windows be had it not been invented by Microsoft, but by Google? the answer pops up as "Android." When you subtract "copper" from "Cu" and add "gold," you get "Au" as the chemical symbol of gold. This literally means we don't have to code these manually anymore. It seems that the computer can make all the inferences out of the data we provide it with all by itself. This is the yummiest example of all. When you take "Japan" out of "sushi" and add "Germany," you get the "bratwurst," the German favorite. Too good to be true, right? Happy now? We finalized this project. Would computers understand what we say? Are we having fun? Not much. Now, I'll tell you about a Turkish researcher. Tolga Bölükbaşı is about to finish his PhD at Boston University in the States. This is a research he did two years ago. Tolga did the same thing as Mikolov did previously, but this time on news texts. What happens when you subtract "father" from "doctor" and add "mom"? "My dad is a doctor, and mom is a nurse." What about when you subtract "man" from "computer engineer" and add "woman"? In fact, we shouldn't have gender. Let's see how professions are related to gender in the meaning space in the head of the computer. You get "homemaker." Seriously! You get "homemaker." We get an English word "homemaker." So, it's clear that we not only put all of our data in computers but also put all of our prejudices. Imagine if this computer were used to hire someone. You've already uploaded your resume and all the personal information including your gender. Let's assume 10,000 people applied for the job. The computer needs to do a pre-selection, right? It needs to get to 1,000 candidates, eliminating 9,000 others so that the HR staff can evaluate the results. Computers nowadays are already used for this kind of work. Let's say that a computer loaded with such meaning vectors makes selection among the candidates who have applied for a job vacancy for a computer engineer. It might automatically eliminate all the female candidates, thinking that a computer engineer should be male. Tolga and his colleagues also mention other cases. It was found out that computers link positive and negative attributions with the words related to being Afro-American and Caucasian. For instance, the computer thinks that the word "mugger" is closely related to being Afro-American. It's certain that we uploaded all our prejudices while uploading all the information we have in computers. You might ask yourselves, What will happen now? Tolga and his team's article offers a solution to that. Just told you. All these things happen in the vector space. Each word has its vector. We already know from high school years that we can add and subtract them. Tolga and his team first list the words that are really feminine or masculine, like "dad," "uncle," "grandmother," and so on. These words really should have a relation to male and female roles. Then there are these words which should not be masculine or feminine despite having closer meanings in the computer's space. For example, the word "genius" appears to be male. On the other hand, the word "stylist" stands out as a very female word. It doesn't have to be like that. So, after listing all the words that need to be feminine or masculine, Tolga and his team created an algorithm which would automatically erase the computer's prejudices on the ones that should be neutral. If a word like "father" or "uncle" is not in the list, but it is still biased towards a gender in the space of meanings, the algorithm automatically corrects it. With the help of this, "computer programmer" ends up at the same distance to the male and female notions, and the problems I talked about go away. Isn't that beautiful? I wish we could delete the prejudices in the human brain so easily. For a while, some people have been worrying about what would happen if computers took over. On the other hand, considering the fact that we can't delete the prejudices in people, while we can in computers, maybe we could give computers a chance at jobs requiring fairness such as being referees, judges, and managers and let people take a rest for a while. What do you say to that? Thank you. (Applause)

Related talks

David J. Malan: What's an algorithm?

Shimon Schocken: The self-organizing computer course

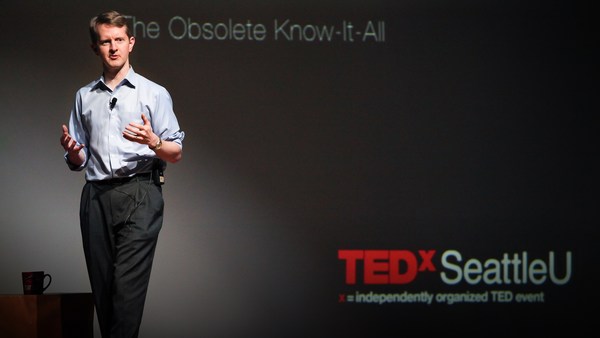

Ken Jennings: Watson, Jeopardy and me, the obsolete know-it-all

Sugata Mitra: Build a School in the Cloud

Shyam Sankar: The rise of human-computer cooperation