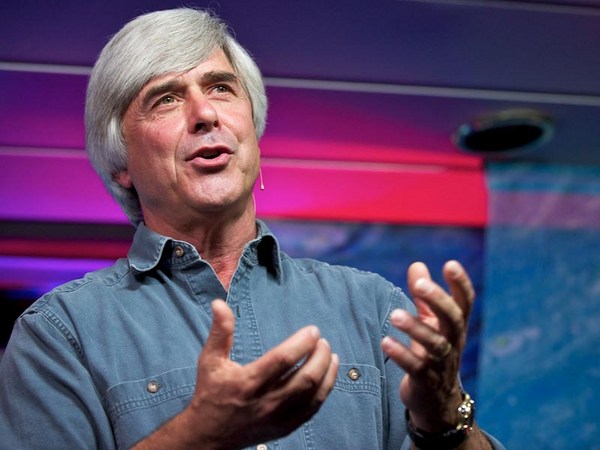

I would like to share with you this morning some stories about the ocean through my work as a still photographer for National Geographic magazine. I guess I became an underwater photographer and a photojournalist because I fell in love with the sea as a child. And I wanted to tell stories about all the amazing things I was seeing underwater, incredible wildlife and interesting behaviors. And after even 30 years of doing this, after 30 years of exploring the ocean, I never cease to be amazed at the extraordinary encounters that I have while I'm at sea. But more and more frequently these days I'm seeing terrible things underwater as well, things that I don't think most people realize. And I've been compelled to turn my camera towards these issues to tell a more complete story. I want people to see what's happening underwater, both the horror and the magic.

The first story that I did for National Geographic, where I recognized the ability to include environmental issues within a natural history coverage, was a story I proposed on harp seals. The story I wanted to do initially was just a small focus to look at the few weeks each year where these animals migrate down from the Canadian arctic to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada to engage in courtship, mating and to have their pups. And all of this is played out against the backdrop of transient pack ice that moves with wind and tide. And because I'm an underwater photographer, I wanted to do this story from both above and below, to make pictures like this that show one of these little pups making its very first swim in the icy 29-degree water. But as I got more involved in the story, I realized that there were two big environmental issues I couldn't ignore. The first was that these animals continue to be hunted, killed with hakapiks at about eight, 15 days old. It actually is the largest marine mammal slaughter on the planet, with hundreds of thousands of these seals being killed every year.

But as disturbing as that is, I think the bigger problem for harp seals is the loss of sea ice due to global warming. This is an aerial picture that I made that shows the Gulf of St. Lawrence during harp seal season. And even though we see a lot of ice in this picture, there's a lot of water as well, which wasn't there historically. And the ice that is there is quite thin. The problem is that these pups need a stable platform of solid ice in order to nurse from their moms. They only need 12 days from the moment they're born until they're on their own. But if they don't get 12 days, they can fall into the ocean and die. This is a photo that I made showing one of these pups that's only about five or seven days old -- still has a little bit of the umbilical cord on its belly -- that has fallen in because of the thin ice, and the mother is frantically trying to push it up to breathe and to get it back to stable purchase. This problem has continued to grow each year since I was there. I read that last year the pup mortality rate was 100 percent in parts of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. So, clearly, this species has a lot of problems going forward. This ended up becoming a cover story at National Geographic. And it received quite a bit of attention.

And with that, I saw the potential to begin doing other stories about ocean problems. So I proposed a story on the global fish crisis, in part because I had personally witnessed a lot of degradation in the ocean over the last 30 years, but also because I read a scientific paper that stated that 90 percent of the big fish in the ocean have disappeared in the last 50 or 60 years. These are the tuna, the billfish and the sharks. When I read that, I was blown away by those numbers. I thought this was going to be headline news in every media outlet, but it really wasn't, so I wanted to do a story that was a very different kind of underwater story. I wanted it to be more like war photography, where I was making harder-hitting pictures that showed readers what was happening to marine wildlife around the planet.

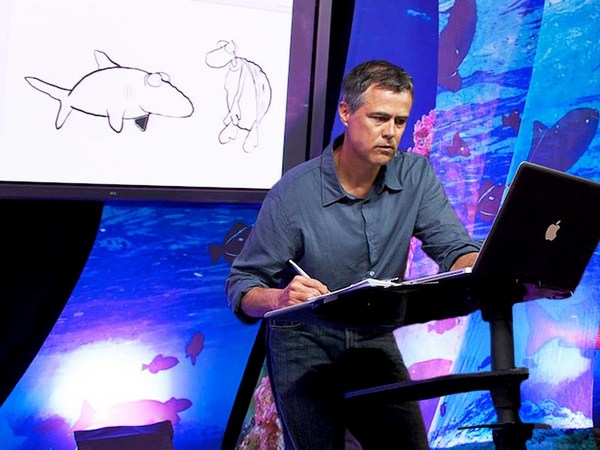

The first component of the story that I thought was essential, however, was to give readers a sense of appreciation for the ocean animals that they were eating. You know, I think people go into a restaurant, and somebody orders a steak, and we all know where steak comes from, and somebody orders a chicken, and we know what a chicken is, but when they're eating bluefin sushi, do they have any sense of the magnificent animal that they're consuming? These are the lions and tigers of the sea. In reality, these animals have no terrestrial counterpart; they're unique in the world. These are animals that can practically swim from the equator to the poles and can crisscross entire oceans in the course of a year. If we weren't so efficient at catching them, because they grow their entire life, would have 30-year-old bluefin out there that weigh a ton. But the truth is we're way too efficient at catching them, and their stocks have collapsed worldwide.

This is the daily auction at the Tsukiji Fish Market that I photographed a couple years ago. And every single day these tuna, bluefin like this, are stacked up like cordwood, just warehouse after warehouse. As I wandered around and made these pictures, it sort of occurred to me that the ocean's not a grocery store, you know. We can't keep taking without expecting serious consequences as a result.

I also, with the story, wanted to show readers how fish are caught, some of the methods that are used to catch fish, like a bottom trawler, which is one of the most common methods in the world. This was a small net that was being used in Mexico to catch shrimp, but the way it works is essentially the same everywhere in the world. You have a large net in the middle with two steel doors on either end. And as this assembly is towed through the water, the doors meet resistance with the ocean, and it opens the mouth of the net, and they place floats at the top and a lead line on the bottom. And this just drags over the bottom, in this case to catch shrimp. But as you can imagine, it's catching everything else in its path as well. And it's destroying that precious benthic community on the bottom, things like sponges and corals, that critical habitat for other animals.

This photograph I made of the fisherman holding the shrimp that he caught after towing his nets for one hour. So he had a handful of shrimp, maybe seven or eight shrimp, and all those other animals on the deck of the boat are bycatch. These are animals that died in the process, but have no commercial value. So this is the true cost of a shrimp dinner, maybe seven or eight shrimp and 10 pounds of other animals that had to die in the process. And to make that point even more visual, I swam under the shrimp boat and made this picture of the guy shoveling this bycatch into the sea as trash and photographed this cascade of death, you know, animals like guitarfish, bat rays, flounder, pufferfish, that only an hour before, were on the bottom of the ocean, alive, but now being thrown back as trash.

I also wanted to focus on the shark fishing industry because, currently on planet Earth, we're killing over 100 million sharks every single year. But before I went out to photograph this component, I sort of wrestled with the notion of how do you make a picture of a dead shark that will resonate with readers You know, I think there's still a lot of people out there who think the only good shark is a dead shark. But this one morning I jumped in and found this thresher that had just recently died in the gill net. And with its huge pectoral fins and eyes still very visible, it struck me as sort of a crucifixion, if you will. This ended up being the lead picture in the global fishery story in National Geographic. And I hope that it helped readers to take notice of this problem of 100 million sharks.

And because I love sharks -- I'm somewhat obsessed with sharks -- I wanted to do another, more celebratory, story about sharks, as a way of talking about the need for shark conservation. So I went to the Bahamas because there're very few places in the world where sharks are doing well these days, but the Bahamas seem to be a place where stocks were reasonably healthy, largely due to the fact that the government there had outlawed longlining several years ago. And I wanted to show several species that we hadn't shown much in the magazine and worked in a number of locations.

One of the locations was this place called Tiger Beach, in the northern Bahamas where tiger sharks aggregate in shallow water. This is a low-altitude photograph that I made showing our dive boat with about a dozen of these big old tiger sharks sort of just swimming around behind. But the one thing I definitely didn't want to do with this coverage was to continue to portray sharks as something like monsters. I didn't want them to be overly threatening or scary. And with this photograph of a beautiful 15-feet, probably 14-feet, I guess, female tiger shark, I sort of think I got to that goal, where she was swimming with these little barjacks off her nose, and my strobe created a shadow on her face. And I think it's a gentler picture, a little less threatening, a little more respectful of the species.

I also searched on this story for the elusive great hammerhead, an animal that really hadn't been photographed much until maybe about seven or 10 years ago. It's a very solitary creature. But this is an animal that's considered data deficient by science in both Florida and in the Bahamas. You know, we know almost nothing about them. We don't know where they migrate to or from, where they mate, where they have their pups, and yet, hammerhead populations in the Atlantic have declined about 80 percent in the last 20 to 30 years. You know, we're losing them faster than we can possibly find them.

This is the oceanic whitetip shark, an animal that is considered the fourth most dangerous species, if you pay attention to such lists. But it's an animal that's about 98 percent in decline throughout most of its range. Because this is a pelagic animal and it lives out in the deeper water, and because we weren't working on the bottom, I brought along a shark cage here, and my friend, shark biologist Wes Pratt is inside the cage. You'll see that the photographer, of course, was not inside the cage here, so clearly the biologist is a little smarter than the photographer I guess.

And lastly with this story, I also wanted to focus on baby sharks, shark nurseries. And I went to the island of Bimini, in the Bahamas, to work with lemon shark pups. This is a photo of a lemon shark pup, and it shows these animals where they live for the first two to three years of their lives in these protective mangroves. This is a very sort of un-shark-like photograph. It's not what you typically might think of as a shark picture. But, you know, here we see a shark that's maybe 10 or 11 inches long swimming in about a foot of water. But this is crucial habitat and it's where they spend the first two, three years of their lives, until they're big enough to go out on the rest of the reef. After I left Bimini, I actually learned that this habitat was being bulldozed to create a new golf course and resort.

And other recent stories have looked at single, flagship species, if you will, that are at risk in the ocean as a way of talking about other threats. One such story I did documented the leatherback sea turtle. This is the largest, widest-ranging, deepest-diving and oldest of all turtle species. Here we see a female crawling out of the ocean under moonlight on the island of Trinidad. These are animals whose lineage dates back about 100 million years. And there was a time in their lifespan where they were coming out of the water to nest and saw Tyrannosaurus rex running by. And today, they crawl out and see condominiums. But despite this amazing longevity, they're now considered critically endangered. In the Pacific, where I made this photograph, their stocks have declined about 90 percent in the last 15 years.

This is a photograph that shows a hatchling about to taste saltwater for the very first time beginning this long and perilous journey. Only one in a thousand leatherback hatchlings will reach maturity. But that's due to natural predators like vultures that pick them off on a beach or predatory fish that are waiting offshore. Nature has learned to compensate with that, and females have multiple clutches of eggs to overcome those odds. But what they can't deal with is anthropogenic stresses, human things, like this picture that shows a leatherback caught at night in a gill net. I actually jumped in and photographed this, and with the fisherman's permission, I cut the turtle out, and it was able to swim free. But, you know, thousands of other leatherbacks each year are not so fortunate, and the species' future is in great danger.

Another charismatic megafauna species that I worked with is the story I did on the right whale. And essentially, the story is this with right whales, that about a million years ago, there was one species of right whale on the planet, but as land masses moved around and oceans became isolated, the species sort of separated, and today we have essentially two distinct stocks. We have the Southern right whale that we see here and the North Atlantic right whale that we see here with a mom and calf off the coast of Florida. Now, both species were hunted to the brink of extinction by the early whalers, but the Southern right whales have rebounded a lot better because they're located in places farther away from human activity.

The North Atlantic right whale is listed as the most endangered species on the planet today because they are urban whales; they live along the east coast of North America, United States and Canada, and they have to deal with all these urban ills. This photo shows an animal popping its head out at sunset off the coast of Florida. You can see the coal burning plant in the background. They have to deal with things like toxins and pharmaceuticals that are flushed out into the ocean, and maybe even affecting their reproduction. They also get entangled in fishing gear. This is a picture that shows the tail of a right whale. And those white markings are not natural markings. These are entanglement scars. 72 percent of the population has such scars, but most don't shed the gear, things like lobster traps and crab pots. They hold on to them, and it eventually kills them. And the other problem is they get hit by ships. And this was an animal that was struck by a ship in Nova Scotia, Canada being towed in, where they did a necropsy to confirm the cause of death, which was indeed a ship strike. So all of these ills are stacking up against these animals and keeping their numbers very low.

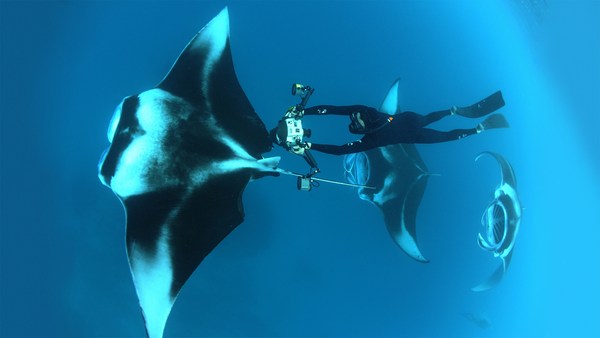

And to draw a contrast with that beleaguered North Atlantic population, I went to a new pristine population of Southern right whales that had only been discovered about 10 years ago in the sub-Antarctic of New Zealand, a place called the Auckland Islands. I went down there in the winter time. And these are animals that had never seen humans before, and I was one of the first people they probably had ever seen. And I got in the water with them, and I was amazed at how curious they were. This photograph shows my assistant standing on the bottom at about 70 feet and one of these amazingly beautiful, 45-foot, 70-ton whales, like a city bus just swimming up, you know. They were in perfect condition, very fat and healthy, robust, no entanglement scars, the way they're supposed to look. You know, I read that the pilgrims, when they landed at Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts in 1620, wrote that you could walk across Cape Cod Bay on the backs of right whales. And we can't go back and see that today, but maybe we can preserve what we have left.

And I wanted to close this program with a story of hope, a story I did on marine reserves as sort of a solution to the problem of overfishing, the global fish crisis story. I settled on working in the country of New Zealand because New Zealand was rather progressive, and is rather progressive in terms of protecting their ocean. And I really wanted this story to be about three things: I wanted it to be about abundance, about diversity and about resilience. And one of the first places I worked was a reserve called Goat Island in Leigh of New Zealand. What the scientists there told me was that when protected this first marine reserve in 1975, they hoped and expected that certain things might happen.

For example, they hoped that certain species of fish like the New Zealand snapper would return because they had been fished to the brink of commercial extinction. And they did come back. What they couldn't predict was that other things would happen. For example, these fish predate on sea urchins, and when the fish were all gone, all anyone ever saw underwater was just acres and acres of sea urchins. But when the fish came back and began predating and controlling the urchin population, low and behold, kelp forests emerged in shallow water. And that's because the urchins eat kelp. So when the fish control the urchin population, the ocean was restored to its natural equilibrium. You know, this is probably how the ocean looked here one or 200 years ago, but nobody was around to tell us.

I worked in other parts of New Zealand as well, in beautiful, fragile, protected areas like in Fiordland, where this sea pen colony was found. Little blue cod swimming in for a dash of color. In the northern part of New Zealand, I dove in the blue water, where the water's a little warmer, and photographed animals like this giant sting ray swimming through an underwater canyon. Every part of the ecosystem in this place seems very healthy, from tiny, little animals like a nudibrank crawling over encrusting sponge or a leatherjacket that is a very important animal in this ecosystem because it grazes on the bottom and allows new life to take hold.

And I wanted to finish with this photograph, a picture I made on a very stormy day in New Zealand when I just laid on the bottom amidst a school of fish swirling around me. And I was in a place that had only been protected about 20 years ago. And I talked to divers that had been diving there for many years, and they said that the marine life was better here today than it was in the 1960s. And that's because it's been protected, that it has come back.

So I think the message is clear. The ocean is, indeed, resilient and tolerant to a point, but we must be good custodians. I became an underwater photographer because I fell in love with the sea, and I make pictures of it today because I want to protect it, and I don't think it's too late.

Thank you very much.