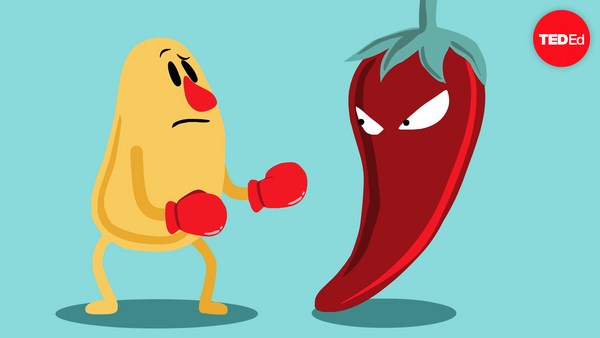

Can we save our planet? Will we continue to have access to water, food, energy, and other ecosystem goods that our planet provides? Each hour, three species disappear. Each day, 10.000 people die from water shortage or contamination. Fourteen billion pounds of garbage are dumped into the ocean every year; most of it is plastic, and it will take nearly a thousand years for it to degrade. Due to global warming, the Arctic may be ice free, and thousands of cities, including New York City, may be underwater. You've all undoubtedly heard of many of these statistics before, and likely, at least so far, you aren't impressed. (Laughter) Yet still, in some sense, these facts turned societal platitudes, motivate us. They certainly motivate me, and I, perhaps like many of you, am the typical environmentalist. I gleefully present my refillable cup to the Starbucks barista, I love to shop at Trader Joe's, and I always bring my "Go green" bag. If you are anything like me, I spend one to two minutes in a fit of confusion trying to recycle the fork, bowl, napkin, and food that constitutes my salad. While my New Yorker instinct is to avoid eye contact with an over-eager side walk soliciting environmentalist, I proudly flash them a smile. Simply to remind them that I support what they do. And as I reflect on my eco-friendly day, I sleep like a baby knowing I made a difference. I know what you are thinking, "You could do so much more," and you'd be right. I could do a lot more. I could compost, and I don't. I could walk to work through Central Park, and I don't. As one environmental campaign suggested, I could get clean and save water by showering with a friend or even an attractive stranger. (Laughter) Don't get too excited for me, I shower alone, often, for many minutes at a time. (Laughter) Undoubtedly, we all could do more, but what if I told you that I did make a more difficult sacrifice for our planet? What if I told you that I am a vegan? (Laughter) Did you feel that? (Laughter) You did. One word and everyone gets a little bit nervous. You can be honest with me, this is TEDx, it's a safe space, you feel a little awkward. Why? Because I am a vegan? And presumably, many of you are not? What is that about? Well, we've all had that conversation before. You are out to dinner with a friend or colleague, and you learn that the person you are with is a vegan. You had no idea, you are surprised, and while the person in front of you may not look like this (Laughter) or like this, your perception of them has immediately changed. There is no going back to whatever it was you thought of them before this moment. Back at dinner, the vegan likely feels compelled to explain to you that while he or she is a vegan, by no means does your culinary decision inspire offense. You, in turn, decide to kindly acknowledge that reconciling gesture, and attempt to, very quickly, move the conversation along to a more unifying topic. Yet, you still feel whatever it is you or your neighbor might be feeling right now. A tinge of nervousness, a pulse of discomfort, the manifestation of a mouth twinge, or the eyes widening. There is me, and then there is you. And somehow, our perception of one another is no longer the same. Well, as it turns out, I am not a vegan. (Laughter) Uff! (Laughter) I am sorry to all the vegans in the room who have lost one of their own. (Laughter) To the rest of you, you can safely take a deep sigh of relief knowing I'm a carnivore just like you. But whatever connotations are in the word vegan, and the experiences those connotations create in our mind, I am absolutely fascinated by them, and think they may hold, at least in part, a key to solving complex problems like global warming and the loss of biodiversity. Semantics aside for just a moment, we all know that vegans and vegetarians, the modern day pioneers abstaining from meat, are onto something, even if we ourselves choose to eat eggs and meat. We know our planet is in trouble, and we know that meat production, from the clearing of lands and trees to the transportation of these products accounts for nearly 20% of global green house gas emissions; 20%. That is why a vegetarian's footprint is nearly half that of a meat lover's. And for a vegan, it's even lower. We also know that meat production requires a lot of water. Producing just one pound of meat protein requires ten times the amount of water as producing one pound of grain protein. It's a lot of water. We also know, perhaps most morally salient, that due to factory farming, animals are not treated very well. They're not. They are incredibly smart and experience pain just like us. So as we look into the eyes of this very adorable baby pig, we have to ask ourselves, "Why do over 90% of Americans continue to eat meat?" Bacon! (Laughter) Bacon is the reason we eat meat. For many, the mere smell of bacon in the morning, that crispy crunchy texture, that savory salty taste, they give us a reason to smile. That spicy buffalo wing, that juicy steak, they are the reason we eat meat. They satisfy our most primal urges. So what should we do? On the one hand, we know that meat gives us a reason to smile in the morning, and on the other, we know it straddles our instincts to uphold our sense of morality, with it's questionable impact on the planet. Plus, as some of the medical literature suggest, meat may not be very healthy for us. Certainly, we can treat each meal as a choice, as it you indulge, or make a more restrained decision, we could simply eat less meat and more fruits and vegetables. That seems simple enough, and as many have suggested, if we simply followed a meatless Monday diet, whereby we abstain from eating meat on Mondays, we'd have a billion vegetarians overnight. That would be huge. But what is a person who eats less meat? They may not be a vegetarian, or vegan, or even on any particular diet. Where do they fall on the spectrum? I've discovered that there are a few words, each with their own connotations, to describe a person who eats less meat. You could say: I am a semi-vegetarian, I sometimes eat meat, and sometimes I don't. You could say: I am a mostly-vegetarian, I mostly eat fruits and vegetables, I sometimes eat meat, but I try not to eat a lot of it. Or you could say, and this one is by far my favorite: that I am flexitarian; I am flexible about it. (Laughter) Sometimes I eat meat, and sometimes I don't. So, imagine we're back at dinner, and the person you're with has just explained to you that he or she is a vegan. You decide to enthusiastically share that you get it, "I am a flexitarian!" "I am flexible about it!" (Laughter) "I sometimes eat meat, and sometimes I don't, but I try not to eat a lot of it." As you continue to eat your steak, and here she continues to eat her vegetable kheema ball, you realize, perhaps unconsciously, that you still fall somewhere different along this moral landscape. We know with simple intuition, that flexitarian sounds, well, flexible. That by choosing to eat meat sometimes, as opposed to never eating meat, you alter your moral standards for primal urges and convenience. It's weak, and it's inconsistent. As we know from advances in cognitive science, the brain does not do well with inconsistencies, it loves false dichotomies, and need compartmentalization. And we can see how this plays out, one minute, you are a noble lover of all forms of life, and the next, you are a ravenous animal, or at least, ravenously eating one. So, whatever it is about words like flexitarian and vegan, we know they conjure entirely different perceptions of who we are. And that these perceptions matter. This seemingly innocuous labels to describe our eating choices matter a great deal. They determine how seriously we are taken, how our messages are understood, and our feeling of belonging. Consider our related example, climate change versus global warming. Scientifically, they have different meanings, one refers to climate, while the other temperature alone, but regardless of what they actually mean, they conjure different mental associations. A 2014 study from Yale University found that the term 'global warming' was associated with greater public understanding, more emotional engagement and support for personal and collective action than the term 'climate change.' Global warming generates more intense worries and negative reactions than climate change. That is why I try to use the phrase 'global warming' more than 'climate change.' So, we see the same type of problem with words like flexitarian and semi-vegetarian. They all describe incredibly positive steps to the more sustainable planet, but they largely invoke negative associations, feelings of division, and moral incompatibility. So it occurred to me, we need a word that describes a community of individuals who are committed to reducing their consumption of meat, and can encourage others to reduce their consumption of cows, chickens, pigs, lambs, and seafood. It is my hope that this word is 'reducitarian.' That it can inspire a community of individuals to simply eat less meat. I bet many of you here today are already reducitarians. How many of you try to eat less meat? You are all reducitarians already. And to my vegan and vegetarian friends, you too are reducitarians, because you are so very much committed to reducing your consumption of meat. Reducitarianism is the practice of reducing one's personal consumption of meat; red meat, seafood, and poultry. Reducitarians may still enjoy the taste of meat, or not concerned with making a drastic lifestyle change, but they are committed to reducing their consumption of meat nonetheless. With more fruits and veggies, reducitarians live longer, healthier, and happier lives. They set manageable and therefore, actionable goals to gradually reduce their meat consumption. For example, they may order a smaller steak, or skip eating meat for dinner if they had it for lunch, or simply eat meat only on the weekends. Reducitarians know that by choosing to eat less meat, they are not only going to improve themselves and the environment, but farm animals, as well. The concept of reducitarianism is appealing because not everyone is able or willing to follow a completely vegetarian diet. This is a difficult but important realization; not everyone is able or willing to follow a completely vegetarian diet. A Gallup poll conducted in 2012 asked a diverse group of Americans the following question, "In terms of your eating preference, do you consider yourself to be a vegetarian or not?" How would you respond? What do you think they found? What they found was that on average, only 5% of Americans consider themselves to be a vegetarian. But what was so interesting about this 5% is that it remained largely unchanged from the 6% that was recorded in 1999 and 2001. In other words, the amount of vegetarians in the United States has remained about the same: extremely low. As you might imagine, this percentage is even lower for vegans. Similar statistics have been observed throughout the world. just in case you aren't convinced, a separate study found that among those who consider themselves to be a vegetarian nearly two-thirds of them had indicated that they've recently eaten meat when they were asked to recall their diet. These individuals were not vegetarians or vegans, they were reducitarians. But they were forced to play mental gymnastics with themselves without a word to describe who they are. And this used to happen to me all the time. My friends and family knew that I was a vegetarian. Once in a while, we would go out to eat, I'd order bacon with my eggs and pancakes, and they would literally catch me in the act red handed, eating a slice of bacon. (Laughter) Do you know what it's like for a Jewish vegetarian to be caught eating bacon? (Laughter) That is a double whammy no one wants to experience with their morning coffee. So look, what I think this means is that even though we know it would be better, more healthy, and environmentally friendly if everyone just stopped eating meat. This is an ideal, a romantic ideal, that we have been unable to achieve. This message of completely eliminating meat consumption has worked very well, or somewhat well, for the individuals who are vegetarians or vegans, but has failed to capture the attention of the rest of us. The 95% of us who continue to inhabit this planet. So yes, reducitarianism is a message for the 95% of us. We should consider eating less meat for the sake of our health and the environment. We can learn a lot from vegans and vegetarians who have so admirably reduced their meat consumption, that they effectively eat none at all. But vegans and vegetarians can also learn a great deal from those who simply strive to eat less meat. In many ways, the use of categorical imperatives that we must never eat meat, has put vegans and vegetarians and those who simply strive to eat less meat in a boxing match for moral superiority. It's exhausting, and as the data suggests, largely unproductive. Reducitarianism is a message that allows us to focus not on our differences but on our shared commitment to eating less meat, regardless of where we fall on the spectrum. I believe that this reducitarian message will absolutely terrify the meat industry. Because it is a message that will produce the greatest impact on the causes we all care so deeply about. After all, what could possibly matter more than the increased well-being of our health and the environment. It is my hope that we can leverage "reducitarian." A positive and inclusive term of moral worth to encourage ourselves and others to eat less meat, improving our health, and the environment, and making a lot of animals very happy in the process. It starts with us, all of us, to encourage ourselves and others to simply eat less meat. So this is my message to you, consider eating less meat this week, and be a reducitarian. You can change the world by ordering a smaller steak, or doing something more. But don't just sit by and ignore what you already know. Consider eating less meat and be a reducitarian. Save our planet, improve your health, and save a lot of animals. Thank you so much. (Applause)