It's a great honor to be here with you. The good news is I'm very aware of my responsibilities to get you out of here because I'm the only thing standing between you and the bar. (Laughter) And the good news is I don't have a prepared speech, but I have a box of slides. I have some pictures that represent my life and what I do for a living. I've learned through experience that people remember pictures long after they've forgotten words, and so I hope you'll remember some of the pictures I'm going to share with you for just a few minutes.

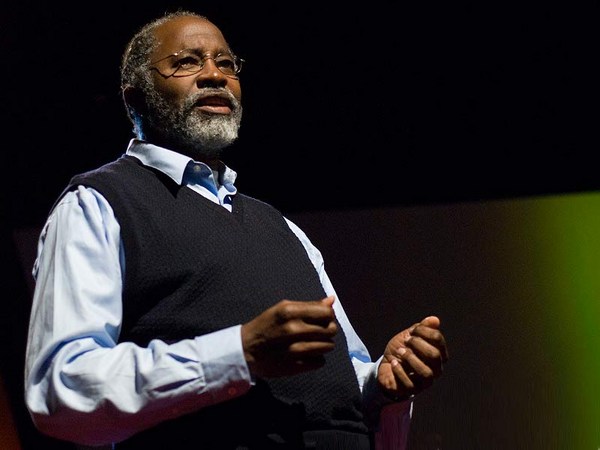

The whole story really starts with me as a high school kid in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in a tough neighborhood that everybody gave up on for dead. And on a Wednesday afternoon, I was walking down the corridor of my high school kind of minding my own business. And there was this artist teaching, who made a great big old ceramic vessel, and I happened to be looking in the door of the art room -- and if you've ever seen clay done, it's magic -- and I'd never seen anything like that before in my life. So, I walked in the art room and I said, "What is that?" And he said, "Ceramics. And who are you?" And I said, "I'm Bill Strickland. I want you to teach me that." And he said, "Well, get your homeroom teacher to sign a piece of paper that says you can come here, and I'll teach it to you." And so for the remaining two years of my high school, I cut all my classes. (Laughter) But I had the presence of mind to give the teachers' classes that I cut the pottery that I made, (Laughter) and they gave me passing grades. And that's how I got out of high school.

And Mr. Ross said, "You're too smart to die and I don't want it on my conscience, so I'm leaving this school and I'm taking you with me." And he drove me out to the University of Pittsburgh where I filled out a college application and got in on probation. Well, I'm now a trustee of the university, and at my installation ceremony I said, "I'm the guy who came from the neighborhood who got into the place on probation. Don't give up on the poor kids, because you never know what's going to happen to those children in life."

What I'm going to show you for a couple of minutes is a facility that I built in the toughest neighborhood in Pittsburgh with the highest crime rate. One is called Bidwell Training Center; it is a vocational school for ex-steel workers and single parents and welfare mothers. You remember we used to make steel in Pittsburgh? Well, we don't make any steel anymore, and the people who used to make the steel are having a very tough time of it. And I rebuild them and give them new life.

Manchester Craftsmen's Guild is named after my neighborhood. I was adopted by the Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese during the riots, and he donated a row house. And in that row house I started Manchester Craftsmen's Guild, and I learned very quickly that wherever there are Episcopalians, there's money in very close proximity. (Laughter) And the Bishop adopted me as his kid. And last year I spoke at his memorial service and wished him well in this life. I went out and hired a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, the architect, and I asked him to build me a world class center in the worst neighborhood in Pittsburgh. And my building was a scale model for the Pittsburgh airport. And when you come to Pittsburgh -- and you're all invited -- you'll be flying into the blown-up version of my building. That's the building. Built in a tough neighborhood where people have been given up for dead.

My view is that if you want to involve yourself in the life of people who have been given up on, you have to look like the solution and not the problem. As you can see, it has a fountain in the courtyard. And the reason it has a fountain in the courtyard is I wanted one and I had the checkbook, so I bought one and put it there. (Laughter) And now that I'm giving speeches at conferences like TED, I got put on the board of the Carnegie Museum. At a reception in their courtyard, I noticed that they had a fountain because they think that the people who go to the museum deserve a fountain. Well, I think that welfare mothers and at-risk kids and ex-steel workers deserve a fountain in their life. And so the first thing that you see in my center in the springtime is water that greets you -- water is life and water of human possibility -- and it sets an attitude and expectation about how you feel about people before you ever give them a speech. So, from that fountain I built this building.

As you can see, it has world class art, and it's all my taste because I raised all the money. (Laughter) I said to my boy, "When you raise the money, we'll put your taste on the wall." That we have quilts and clay and calligraphy and everywhere your eye turns, there's something beautiful looking back at you, that's deliberate. That's intentional. In my view, it is this kind of world that can redeem the soul of poor people.

We also created a boardroom, and I hired a Japanese cabinetmaker from Kyoto, Japan, and commissioned him to do 60 pieces of furniture for our building. We have since spun him off into his own business. He's making a ton of money doing custom furniture for rich people. And I got 60 pieces out of it for my school because I felt that welfare moms and ex-steel workers and single parents deserved to come to a school where there was handcrafted furniture that greeted them every day. Because it sets a tone and an attitude about how you feel about people long before you give them the speech.

We even have flowers in the hallway, and they're not plastic. Those are real and they're in my building every day. And now that I've given lots of speeches, we had a bunch of high school principals come and see me, and they said, "Mr. Strickland, what an extraordinary story and what a great school. And we were particularly touched by the flowers and we were curious as to how the flowers got there." I said, "Well, I got in my car and I went out to the greenhouse and I bought them and I brought them back and I put them there." You don't need a task force or a study group to buy flowers for your kids. What you need to know is that the children and the adults deserve flowers in their life. The cost is incidental but the gesture is huge. And so in my building, which is full of sunlight and full of flowers, we believe in hope and human possibilities. That happens to be at Christmas time.

And so the next thing you'll see is a million dollar kitchen that was built by the Heinz company -- you've heard of them? They did all right in the ketchup business. And I happen to know that company pretty well because John Heinz, who was our U.S. senator -- who was tragically killed in a plane accident -- he had heard about my desire to build a new building, because I had a cardboard box and I put it in a garbage bag and I walking all over Pittsburgh trying to raise money for this site. And he called me into his office -- which is the equivalent of going to see the Wizard of Oz (Laughter) -- and John Heinz had 600 million dollars, and at the time I had about 60 cents. And he said, "But we've heard about you. We've heard about your work with the kids and the ex-steel workers, and we're inclined to want to support your desire to build a new building. And you could do us a great service if you would add a culinary program to your program." Because back then, we were building a trades program. He said, "That way we could fulfill our affirmative action goals for the Heinz company." I said, "Senator, I'm reluctant to go into a field that I don't know much about, but I promise you that if you'll support my school, I'll get it built and in a couple of years, I'll come back and weigh out that program that you desire." And Senator Heinz sat very quietly and he said, "Well, what would your reaction be if I said I'd give you a million dollars?" I said, "Senator, it appears that we're going into the food training business." (Laughter) And John Heinz did give me a million bucks. And most importantly, he loaned me the head of research for the Heinz company. And we kind of borrowed the curriculum from the Culinary Institute of America, which in their mind is kind of the Harvard of cooking schools, and we created a gourmet cooks program for welfare mothers in this million dollar kitchen in the middle of the inner city. And we've never looked back.

I would like to show you now some of the food that these welfare mothers do in this million dollar kitchen. That happens to be our cafeteria line. That's puff pastry day. Why? Because the students made puff pastry and that's what the school ate every day. But the concept was that I wanted to take the stigma out of food. That good food's not for rich people -- good food's for everybody on the planet, and there's no excuse why we all can't be eating it. So at my school, we subsidize a gourmet lunch program for welfare mothers in the middle of the inner city because we've discovered that it's good for their stomachs, but it's better for their heads. Because I wanted to let them know every day of their life that they have value at this place I call my center.

We have students who sit together, black kids and white kids, and what we've discovered is you can solve the race problem by creating a world class environment, because people will have a tendency to show you world class behavior if you treat them in that way. These are examples of the food that welfare mothers are doing after six months in the training program. No sophistication, no class, no dignity, no history. What we've discovered is the only thing wrong with poor people is they don't have any money, which happens to be a curable condition. It's all in the way that you think about people that often determines their behavior. That was done by a student after seven months in the program, done by a very brilliant young woman who was taught by our pastry chef. I've actually eaten seven of those baskets and they're very good. (Laughter) They have no calories. That's our dining room. It looks like your average high school cafeteria in your average town in America. But this is my view of how students ought to be treated, particularly once they have been pushed aside.

We train pharmaceutical technicians for the pharmacy industry, we train medical technicians for the medical industry, and we train chemical technicians for companies like Bayer and Calgon Carbon and Fisher Scientific and Exxon. And I will guarantee you that if you come to my center in Pittsburgh -- and you're all invited -- you'll see welfare mothers doing analytical chemistry with logarithmic calculators 10 months from enrolling in the program. There is absolutely no reason why poor people can't learn world class technology. What we've discovered is you have to give them flowers and sunlight and food and expectations and Herbie's music, and you can cure a spiritual cancer every time.

We train corporate travel agents for the travel industry. We even teach people how to read. The kid with the red stripe was in the program two years ago -- he's now an instructor. And I have children with high school diplomas that they can't read. And so you must ask yourself the question: how is it possible in the 21st century that we graduate children from schools who can't read the diplomas that they have in their hands? The reason is that the system gets reimbursed for the kids they spit out the other end, not the children who read. I can take these children and in 20 weeks, demonstrated aptitude; I can get them high school equivalent. No big deal. That's our library with more handcrafted furniture. And this is the arts program I started in 1968.

Remember I'm the black kid from the '60s who got his life saved with ceramics. Well, I went out and decided to reproduce my experience with other kids in the neighborhood, the theory being if you get kids flowers and you give them food and you give them sunshine and enthusiasm, you can bring them right back to life. I have 400 kids from the Pittsburgh public school system that come to me every day of the week for arts education. And these are children who are flunking out of public school. And last year I put 88 percent of those kids in college and I've averaged over 80 percent for 15 years. We've made a fascinating discovery: there's nothing wrong with the kids that affection and sunshine and food and enthusiasm and Herbie's music can't cure. For that I won a big old plaque -- Man of the Year in Education. I beat out all the Ph.D.'s because I figured that if you treat children like human beings, it increases the likelihood they're going to behave that way. And why we can't institute that policy in every school and in every city and every town remains a mystery to me.

Let me show you what these people do. We have ceramics and photography and computer imaging. And these are all kids with no artistic ability, no talent, no imagination. And we bring in the world's greatest artists -- Gordon Parks has been there, Chester Higgins has been there -- and what we've learned is that the children will become like the people who teach them. In fact, I brought in a mosaic artist from the Vatican, an African-American woman who had studied the old Vatican mosaic techniques, and let me show you what they did with the work. These were children who the whole world had given up on, who were flunking out of public school, and that's what they're capable of doing with affection and sunlight and food and good music and confidence.

We teach photography. And these are examples of some of the kids' work. That boy won a four-year scholarship on the strength of that photograph. This is our gallery. We have a world class gallery because we believe that poor kids need a world class gallery, so I designed this thing. We have smoked salmon at the art openings, we have a formal printed invitation, and I even have figured out a way to get their parents to come. I couldn't buy a parent 15 years ago so I hired a guy who got off on the Jesus big time. He was dragging guys out of bars and saving those lives for the Lord. And I said, "Bill, I want to hire you, man. You have to tone down the Jesus stuff a little bit, but keep the enthusiasm. (Laughter) (Applause) I can't get these parents to come to the school." He said, "I'll get them to come to the school." So, he jumped in the van, he went to Miss Jones' house and said, "Miss Jones, I knew you wanted to come to your kid's art opening but you probably didn't have a ride. So, I came to give you a ride." And he got 10 parents and then 20 parents. At the last show that we did, 200 parents showed up and we didn't pick up one parent. Because now it's become socially not acceptable not to show up to support your children at the Manchester Craftsmen's Guild because people think you're bad parents. And there is no statistical difference between the white parents and the black parents. Mothers will go where their children are being celebrated, every time, every town, every city. I wanted you to see this gallery because it's as good as it gets. And by the time I cut these kids loose from high school, they've got four shows on their resume before they apply to college because it's all up here.

You have to change the way that people see themselves before you can change their behavior. And it's worked out pretty good up to this day. I even stuck another room on the building, which I'd like to show you. This is brand new. We just got this slide done in time for the TED Conference. I gave this little slide show at a place called the Silicon Valley and I did all right. And the woman came out of the audience, she said, "That was a great story and I was very impressed with your presentation. My only criticism is your computers are getting a little bit old." And I said, "Well, what do you do for a living?" She said, "Well, I work for a company called Hewlett-Packard." And I said, "You're in the computer business, is that right?" She said, "Yes, sir." And I said, "Well, there's an easy solution to that problem." Well, I'm very pleased to announce to you that HP and a furniture company called Steelcase have adopted us as a demonstration model for all of their technology and all their furniture for the United States of America. And that's the room that's initiating the relationship. We got it just done in time to show you, so it's kind of the world debut of our digital imaging center. (Applause) (Music)

I only have a couple more slides, and this is where the story gets kind of interesting. So, I just want you to listen up for a couple more minutes and you'll understand why he's there and I'm here. In 1986, I had the presence of mind to stick a music hall on the north end of the building while I was building it. And a guy named Dizzy Gillespie showed up to play there because he knew this man over here, Marty Ashby. And I stood on that stage with Dizzy Gillespie on sound check on a Wednesday afternoon, and I said, "Dizzy, why would you come to a black-run center in the middle of an industrial park with a high crime rate that doesn't even have a reputation in music?" He said, "Because I heard you built the center and I didn't believe that you did it, and I wanted to see for myself. And now that I have, I want to give you a gift." I said, "You're the gift." He said, "No, sir. You're the gift. And I'm going to allow you to record the concert and I'm going to give you the music, and if you ever choose to sell it, you must sign an agreement that says the money will come back and support the school." And I recorded Dizzy. And he died a year later, but not before telling a fellow named McCoy Tyner what we were doing. And he showed up and said, "Dizzy talking about you all over the country, man, and I want to help you." And then a guy named Wynton Marsalis showed up. Then a bass player named Ray Brown, and a fellow named Stanley Turrentine, and a piano player named Herbie Hancock, and a band called the Count Basie Orchestra, and a fellow named Tito Puente, and a guy named Gary Burton, and Shirley Horn, and Betty Carter, and Dakota Staton and Nancy Wilson all have come to this center in the middle of an industrial park to sold out audiences in the middle of the inner city. And I'm very pleased to tell you that, with their permission, I have now accumulated 600 recordings of the greatest artists in the world, including Joe Williams, who died, but not before his last recording was done at my school. And Joe Williams came up to me and he put his hand on my shoulder and he said, "God's picked you, man, to do this work. And I want my music to be with you." And that worked out all right.

When the Basie band came, the band got so excited about the school they voted to give me the rights to the music. And I recorded it and we won something called a Grammy. And like a fool, I didn't go to the ceremony because I didn't think we were going to win. Well, we did win, and our name was literally in lights over Madison Square Garden. Then the U.N. Jazz Orchestra dropped by and we recorded them and got nominated for a second Grammy back to back. So, we've become one of the hot, young jazz recording studios in the United States of America (Laughter) in the middle of the inner city with a high crime rate.

That's the place all filled up with Republicans. (Laughter) (Applause) If you'd have dropped a bomb on that room, you'd have wiped out all the money in Pennsylvania because it was all sitting there. Including my mother and father, who lived long enough to see their kid build that building. And there's Dizzy, just like I told you. He was there. And he was there, Tito Puente. And Pat Metheny and Jim Hall were there and they recorded with us. And that was our first recording studio, which was the broom closet. We put the mops in the hallway and re-engineered the thing and that's where we recorded the first Grammy.

And this is our new facility, which is all video technology. And that is a room that was built for a woman named Nancy Wilson, who recorded that album at our school last Christmas. And any of you who happened to have been watching Oprah Winfrey on Christmas Day, he was there and Nancy was there singing excerpts from this album, the rights to which she donated to our school. And I can now tell you with absolute certainty that an appearance on Oprah Winfrey will sell 10,000 CDs. (Laughter) We are currently number four on the Billboard Charts, right behind Tony Bennett. And I think we're going to be fine.

This was burned out during the riots -- this is next to my building -- and so I had another cardboard box built and I walked back out in the streets again. And that's the building, and that's the model, and on the right's a high-tech greenhouse and in the middle's the medical technology building. And I'm very pleased to tell you that the building's done. It's also full of anchor tenants at 20 dollars a foot -- triple that in the middle of the inner city. And there's the fountain. (Laughter) Every building has a fountain. And the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center are anchor tenants and they took half the building, and we now train medical technicians through all their system. And Mellon Bank's a tenant. And I love them because they pay the rent on time. (Laughter) And as a result of the association, I'm now a director of the Mellon Financial Corporation that bought Dreyfus.

And this is in the process of being built as we speak. Multiply that picture times four and you will see the greenhouse that's going to open in October this year because we're going to grow those flowers in the middle of the inner city. And we're going to have high school kids growing Phalaenopsis orchids in the middle of the inner city. And we have a handshake with one of the large retail grocers to sell our orchids in all 240 stores in six states. And our partners are Zuma Canyon Orchids of Malibu, California, who are Hispanic. So, the Hispanics and the black folks have formed a partnership to grow high technology orchids in the middle of the inner city. And I told my United States senator that there was a very high probability that if he could find some funding for this, we would become a left-hand column in the Wall Street Journal, to which he readily agreed. And we got the funding and we open in the fall. And you ought to come and see it -- it's going to be a hell of a story.

And this is what I want to do when I grow up. (Laughter) The brown building is the one you guys have been looking at and I'll tell you where I made my big mistake. I had a chance to buy this whole industrial park -- which is less than 1,000 feet from the riverfront -- for four million dollars and I didn't do it. And I built the first building, and guess what happened? I appreciated the real estate values beyond everybody's expectations and the owners of the park turned me down for eight million dollars last year, and said, "Mr. Strickland, you ought to get the Civic Leader of the Year Award because you've appreciated our property values beyond our wildest expectations. Thank you very much for that." The moral of the story is you must be prepared to act on your dreams, just in case they do come true.

And finally, there's this picture. This is in a place called San Francisco. And the reason this picture's in here is I did this slide show a couple years ago at a big economics summit, and there was a fellow in the audience who came up to me. He said, "Man, that's a great story. I want one of those." I said, "Well, I'm very flattered. What do you do for a living?" He says, "I run the city of San Francisco. My name's Willie Brown." And so I kind of accepted the flattery and the praise and put it out of my mind. And that weekend, I was going back home and Herbie Hancock was playing our center that night -- first time I'd met him. And he walked in and he says, "What is this?" And I said, "Herbie, this is my concept of a training center for poor people." And he said, "As God as my witness, I've had a center like this in my mind for 25 years and you've built it. And now I really want to build one." I said, "Well, where would you build this thing?" He said, "San Francisco." I said, "Any chance you know Willie Brown?" (Laughter) As a matter of fact he did know Willie Brown, and Willie Brown and Herbie and I had dinner four years ago, and we started drawing out that center on the tablecloth. And Willie Brown said, "As sure as I'm the mayor of San Francisco, I'm going to build this thing as a legacy to the poor people of this city." And he got me five acres of land on San Francisco Bay and we got an architect and we got a general contractor and we got Herbie on the board, and our friends from HP, and our friends from Steelcase, and our friends from Cisco, and our friends from Wells Fargo and Genentech.

And along the way, I met this real short guy at my slide show in the Silicon Valley. He came up to me afterwards, he said, "Man, that's a fabulous story. I want to help you." And I said, "Well, thank you very much for that. What do you do for a living?" He said, "Well, I built a company called eBay." I said, "Well, that's very nice. Thanks very much, and give me your card and sometime we'll talk." I didn't know eBay from that jar of water sitting on that piano, but I had the presence of mind to go back and talk to one of the techie kids at my center. I said, "Hey man, what is eBay?" He said, "Well, that's the electronic commerce network." I said, "Well, I met the guy who built the thing and he left me his card." So, I called him up on the phone and I said, "Mr. Skoll, I've come to have a much deeper appreciation of who you are (Laughter) and I'd like to become your friend." (Laughter) And Jeff and I did become friends, and he's organized a team of people and we're going to build this center.

And I went down into the neighborhood called Bayview-Hunters Point, and I said, "The mayor sent me down here to work with you and I want to build a center with you, but I'm not going to build you anything if you don't want it. And all I've got is a box of slides." And so I stood up in front of 200 very angry, very disappointed people on a summer night, and the air conditioner had broken and it was 100 degrees outside, and I started showing these pictures. And after about 10 pictures they all settled down. And I ran the story and I said, "What do you think?" And in the back of the room, a woman stood up and she said, "In 35 years of living in this God forsaken place, you're the only person that's come down here and treated us with dignity. I'm going with you, man." And she turned that audience around on a pin. And I promised these people that I was going to build this thing, and we're going to build it all right. And I think we can get in the ground this year as the first replication of the center in Pittsburgh.

But I met a guy named Quincy Jones along the way and I showed him the box of slides. And Quincy said, "I want to help you, man. Let's do one in L.A." And so he's assembled a group of people. And I've fallen in love with him, as I have with Herbie and with his music. And Quincy said, "Where did the idea for centers like this come from?" And I said, "It came from your music, man. Because Mr. Ross used to bring in your albums when I was 16 years old in the pottery class, when the world was all dark, and your music got me to the sunlight." And I said, "If I can follow that music, I'll get out into the sunlight and I'll be OK. And if that's not true, how did I get here?"

I want you all to know that I think the world is a place that's worth living. I believe in you. I believe in your hopes and your dreams, I believe in your intelligence and I believe in your enthusiasm. And I'm tired of living like this, going into town after town with people standing around on corners with holes where eyes used to be, their spirits damaged. We won't make it as a country unless we can turn this thing around. In Pennsylvania it costs 60,000 dollars to keep people in jail, most of whom look like me. It's 40,000 dollars to build the University of Pittsburgh Medical School. It's 20,000 dollars cheaper to build a medical school than to keep people in jail. Do the math -- it will never work. I am banking on you and I'm banking on guys like Herbie and Quincy and Hackett and Richard and very decent people who still believe in something. And I want to do this in my lifetime, in every city and in every town. And I don't think I'm crazy. I think we can get home on this thing and I think we can build these all over the country for less money than we're spending on prisons. And I believe we can turn this whole story around to one of celebration and one of hope. In my business it's very difficult work. You're always fighting upstream like a salmon -- never enough money, too much need -- and so there is a tendency to have an occupational depression that accompanies my work. And so I've figured out, over time, the solution to the depression: you make a friend in every town and you'll never be lonely. And my hope is that I've made a few here tonight. And thanks for listening to what I had to say. (Applause)