Imagine two universes. In one of these universes, life flourishes on nearly every planet you can encounter. Floating in the atmosphere, swimming in the seas, lounging on the beaches. Life in every body form and size you can imagine.

Now imagine the other universe where life is nowhere to be found. Stars collide, galaxies explode, meteorites crash, asteroids everywhere. A ton of action, but no life. Let me ask you this. Which one of these universes is more interesting to you? Which one has more value?

So today I want to take you to a journey to explore and understand the origin of life, the future and where it is headed and an ethical dilemma that may arise from understanding this. First things first, Earth was formed 4.5 billion years ago. Life happened fairly quickly, within the first few hundred million years. So that's very fast. Think about that next time you feel like you're aging too fast.

(Laughter)

You're not. You're fine. And here is how life works. Life is a form of chemistry. A form of chemistry that explores solutions in response to the problems in its own immediate chemical environment. Life is a form of chemistry that retains a memory of these solutions over billions of years. And life's first solution was quite the trick: copy itself. This is astounding. We would not be standing here today if other tricks didn't follow, like how to use water as a source of electrons or how to use the nitrogen in the atmosphere or how to chew on sunlight. This is remarkable. I am chemistry that explores. I am chemistry that defies degradation, and I am chemistry that remembers. I am a tiny part of an unbroken four-billion-year-old heritage, a four-billion-year-old linkage. Life makes our planet an incredibly exotic place compared to the rest of the known universe. This is the only place that it is known to exist. In fact, you can study physics or chemistry or geology anywhere else in the universe. But this is the only place where you can study biology. Well, I happen to be a biologist on the only planet where you can be a biologist in the entire universe.

(Laughter)

And that makes my job very, very special, right? Because our planet offers an incredible opportunity to explore its own origins and understand how chemistry converted itself into an agent capable of responding to its environment and stimulating itself in response to this. In the past 10 years, there has been remarkable innovations in our understanding of origin of life. I lead a research laboratory, and we are using statistics and mathematical models and evolutionary systems and infer the sequences of ancient DNA that existed billions of years ago. We then synthesize these ancient DNA molecules and engineer them inside organisms. For the first time, we are able to activate molecules that existed billions of years ago to understand and capture what happened back then. We also stimulate and simulate ancient environments in the lab to understand the ingredients by creating them from water, air and rocks. This means accessing and obtaining chemistry that is novel. This means the ability to drive chemical reactions so that they can create chemistry that organizes itself. This means having chemistry in hand that may act lifelike. This is really remarkable.

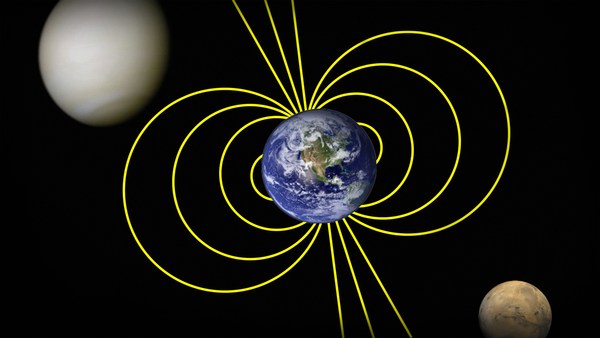

So we might wonder: What do we do when we have this knowledge in our hands? This may mean that we would be able to connect the dots between nonliving and living and understand how chemistry is translating and transforming and transitioning into a lifelike behavior. This may mean that we would be able to obtain the recipe of life, if you will, and having this recipe would enable us to connect the dots between these two states of living and nonliving. This may enable us to look at the particular environments and know how far along is that particular environment from its own unique chemical revolution. We might be able to study different planets and moons and assess them, and assess their chemistry, and know how far along they are from giving birth to life. And we may be able to guide our telescopes in the vast sky in more guided ways in our pursuit of finding life in the universe.

We might also ask ourselves: What can we do with this knowledge? What if you weren't only assessing? What if we were also interacting and engaging with these planets and moons? What if we were able to seed life across the billions of planets in the galaxy? This would not be seeding them with Earth life. This wouldn't be engineering an Earth organism and preadapting them, and preconditioning them in a way that they exist and survive in this other planetary body. No. This this wouldn't be terraforming, altering the environment of this other planet, so that whatever we ship there makes it. No. This would be about empowering and not colonizing these environments. This would be about letting them explore their own unique chemistry to express their own unique reactions by providing them the missing ingredients. This wouldn't be about sending them some life so that we are genetically related or something that is familiar to us. This would be enabling them to do what perhaps they were supposed to do or meant to do all along, but they were lacking and missing ingredients. And not lacking in the sense that they themselves were lacking something important, in the sense that they weren't lacking, right? But what if we were able to send the spice? The secret sauce. Give it a little nudge. For it to react with whatever is already present in this planetary body so that life is sparked, in conjunction and agreement with the own history and journey and origin of this own planetary body, without our meddling, without our direction, without anything that we do to direct this in any way. This would be kickstarting a process that may unfold itself over thousands or millions of years into the future.

But should we do it? This is an extraordinary proposition. And it brings up an extraordinary dilemma about what it means to be alive. Does life, as a chemical system capable of formulating, and in some cases answering, questions about its own existence, have a responsibility or should have a prohibition against sponsoring more life across the universe? Do we do this just because we could? And what is the ethical difference and is there any ethical difference between spreading a particular Earth life versus spreading a potential of life across the galaxy? And where does this difference lie?

So I really tried to bring you answers today, and I don't have any. But I see the facts shaping in front of me. A universe full with life is interesting because having a solution in hand has value, right? But perhaps the spontaneity and unpredictability of discovering novel chemistries and novel life forms is also interesting and has its own unique merits. But do we get to set course and let natural evolution discover its own local environments wherever it might be in the cosmos? An empty universe in this regard, I think, can be viewed as an wide open palette for solutions waiting to be discovered. But should we do it just because we can?

It is very important to keep in mind that Earth is our only home, and it's a good planet. And you know the saying: “Good planets are hard to find.”

(Laughter) I know that, I've been looking for one. I'll let you know when I find a good one.

Exploring the origins may allow us to truly understand life around us, and perhaps an exercise like this may encourage us to truly appreciate and understand how life emerged in the first place. I really think that in order for us to understand the biology and life around us, we really need to understand how life happened to this planet in the first place. I really, really believe in this. I will dedicate my life to do this.

And before I leave to do that, back to my lab that I missed very much, let me ask you again: A universe that is empty and one with a lot of life. Which one of this is more interesting to you?

Thank you. Thank you very much.

Teşekkürler.

(Applause)