I'm going to read a few strips. These are, most of these are from a monthly page I do in and architecture and design magazine called Metropolis.

And the first story is called "The Faulty Switch."

Another beautifully designed new building ruined by the sound of a common wall light switch. It's fine during the day when the main rooms are flooded with sunlight. But at dusk everything changes.

The architect spent hundreds of hours designing the burnished brass switchplates for his new office tower. And then left it to a contractor to install these 79-cent switches behind them.

We know instinctively where to reach when we enter a dark room. We automatically throw the little nub of plastic upward. But the sound we are greeted with, as the room is bathed in the simulated glow of late-afternoon light, recalls to mind a dirty men's room in the rear of a Greek coffee shop. (Laughter)

This sound colors our first impression of any room; it can't be helped. But where does this sound, commonly described as a click, come from? Is it simply the byproduct of a crude mechanical action? Or is it an imitation of one half the set of sounds we make to express disappointment? The often dental consonant of no Indo-European language.

Or is it the amplified sound of a synapse firing in the brain of a cockroach? In the 1950s they tried their best to muffle this sound with mercury switches and silent knob controls.

But today these improvements seem somehow inauthentic. The click is the modern triumphal clarion proceeding us through life, announcing our entry into every lightless room.

The sound made flicking a wall switch off is of a completely different nature. It has a deep melancholy ring. Children don't like it. It's why they leave lights on around the house. (Laughter) Adults find it comforting.

But wouldn't it be an easy matter to wire a wall switch so that it triggers the muted horn of a steam ship? Or the recorded crowing of a rooster? Or the distant peel of thunder?

Thomas Edison went through thousands of unlikely substances before he came upon the right one for the filament of his electric light bulb. Why have we settled so quickly for the sound of its switch? That's the end of that. (Applause)

The next story is called "In Praise of the Taxpayer."

That so many of the city's most venerable taxpayers have survived yet another commercial building boom, is cause for celebration.

These one or two story structures, designed to yield only enough income to cover the taxes on the land on which they stand, were not meant to be permanent buildings. Yet for one reason or another they have confounded the efforts of developers to be combined into lots suitable for high-rise construction.

Although they make no claim to architectural beauty, they are, in their perfect temporariness, a delightful alternative to the large-scale structures that might someday take their place. The most perfect examples occupy corner lots. They offer a pleasant respite from the high-density development around them. A break of light and air, an architectural biding of time.

So buried in signage are these structures, that it often takes a moment to distinguish the modern specially constructed taxpayer from its neighbor: the small commercial building from an earlier century, whose upper floors have been sealed, and whose groundfloor space now functions as a taxpayer. The few surfaces not covered by signs are often clad in a distinctive, dark green-gray, striated aluminum siding. Take-out sandwich shops, film processing drop-offs, peep-shows and necktie stores.

Now these provisional structures have, in some cases, remained standing for the better part of a human lifetime. The temporary building is a triumph of modern industrial organization, a healthy sublimation of the urge to build, and proof that not every architectural idea need be set in stone. That's the end. (Laughter)

And the next story is called, "On the Human Lap." For the ancient Egyptians the lap was a platform upon which to place the earthly possessions of the dead -- 30 cubits from foot to knee.

It was not until the 14th century that an Italian painter recognized the lap as a Grecian temple, upholstered in flesh and cloth. Over the next 200 years we see the infant Christ go from a sitting to a standing position on the Virgin's lap, and then back again. Every child recapitulates this ascension, straddling one or both legs, sitting sideways, or leaning against the body.

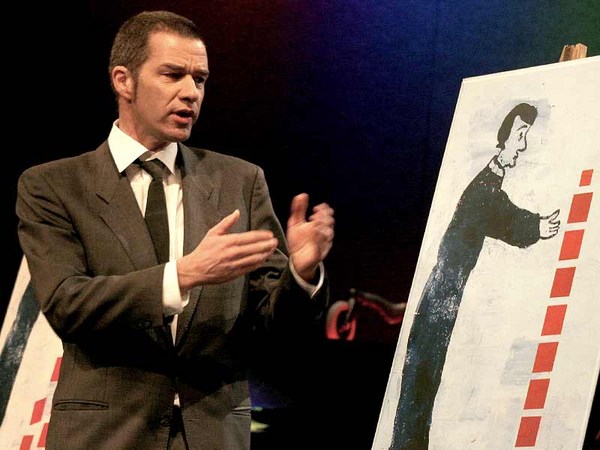

From there, to the modern ventriloquist's dummy, is but a brief moment in history. You were late for school again this morning. The ventriloquist must first make us believe that a small boy is sitting on his lap. The illusion of speech follows incidentally. What have you got to say for yourself, Jimmy?

As adults we admire the lap from a nostalgic distance. We have fading memories of that provisional temple, erected each time an adult sat down. On a crowded bus there was always a lap to sit on. It is children and teenage girls who are most keenly aware of its architectural beauty. They understand the structural integrity of a deep avuncular lap, as compared to the shaky arrangement of a neurotic niece in high heels.

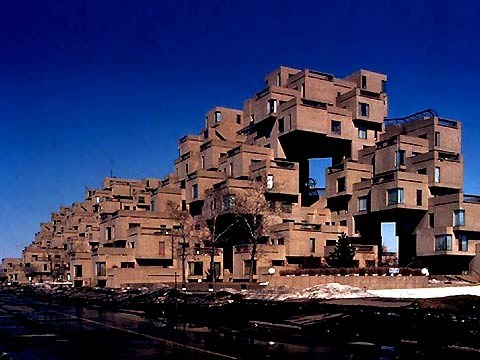

The relationship between the lap and its owner is direct and intimate. I envision a 36-story, 450-unit residential high-rise -- a reason to consider the mental health of any architect before granting an important commission. The bathrooms and kitchens will, of course, have no windows. The lap of luxury is an architectural construct of childhood, which we seek, in vain, as adults, to employ. That's the end. (Laughter)

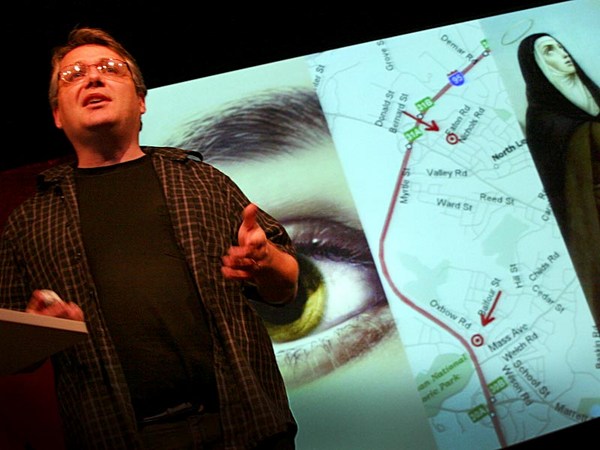

The next story is called "The Haverpiece Collection" A nondescript warehouse, visible for a moment from the northbound lanes of the Prykushko Expressway, serves as the temporary resting place for the Haverpiece collection of European dried fruit.

The profound convolutions on the surface of a dried cherry. The foreboding sheen of an extra-large date.

Do you remember wandering as a child through those dark wooden storefront galleries? Where everything was displayed in poorly labeled roach-proof bins.

Pears dried in the form of genital organs. Apricot halves like the ears of cherubim.

In 1962 the unsold stock was purchased by Maurice Haverpiece, a wealthy prune juice bottler, and consolidated to form the core collection. As an art form it lies somewhere between still-life painting and plumbing.

Upon his death in 1967, a quarter of the items were sold off for compote to a high-class hotel restaurant. (Laughter) Unsuspecting guests were served stewed turn-of-the-century Turkish figs for breakfast. (Laughter)

The rest of the collection remains here, stored in plain brown paper bags until funds can be raised to build a permanent museum and study center.

A shoe made of apricot leather for the daughter of a czar.

That's the end. Thank you. (Applause)