David Biello: In the wake of Dr. Anthony Fauci's announcement that he will be retiring as the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the end of the year, I've invited him to join me for a conversation on the future of the COVID-19 pandemic, reflections on his career and the future of public health. Please welcome Brooklyn's own Dr. Fauci.

Anthony Fauci: Hi, David, nice to see you, thank you for having me.

DB: Thank you for joining us.

So my first question is very simple. Is the COVID-19 pandemic over?

AF: You know, David, there's a lot of misinterpretation about what the meaning of the word "over" is, it means different things to different people. I'm sure you're referring to the comment made by the President a day or two ago. If you're talking about the fulminant phase of the outbreak, when we were having anywhere from 800,000 to 900,000 infections a day and 3,000 to 4,000 deaths per day, that was several months ago. We are much, much better off now than we were then. So in that case, that fulminant phase of the outbreak is behind us. But as the President made very clear on the second half of his sentence, is that, which they don't seem to show, is that he actually said we still have a lot of work to do, there's still a challenge ahead, we’ve got to get people vaccinated. We still have a number of cases, we have 400 deaths per day. That's an unacceptably high level. So again, it depends on the semantics of what your definition is. We don't want anyone to get the impression that we don't have a lot of work to do. We've got to get the level of infection considerably lower than it is. And we've certainly got to get the level of deaths lower than it is. So again, it depends on the semantics of what you mean by "end."

DB: Well, let's get into those semantics then. What conditions would need to exist for the pandemic to be over?

AF: You know, that's a call that officially is made by the World Health Organization. You know, my colleagues and I oh, it must have been more than ten years ago, because of the lack of clarity on what a pandemic means to one person versus another, we wrote a paper in the Journal of Infectious Diseases in which we talked about all the different variations of interpretations. Is it a widespread phenomenon? Is it the widespread nature throughout the world that makes it officially a pandemic? Or is it widespread and accelerating? Or is it widespread causing serious disease? It means different things to different people. So rather than try and give a definition, that's my definition versus another, we should stick with what the WHO is saying. And as Dr. Tedros said, that we're seeing the light at the end of the tunnel on that. So, again, you might interpret that, well, if that's the case, is it over? Well, again, what does "over" mean? There's a lot of semantics there, David. The easiest way not to confuse people is to say we still have a lot of cases, we still have 400 deaths, we only have 67 percent of the population vaccinated, we've got to do better than that. Of those, only one half have gotten a single boost. And as a nation, we lag behind other developed countries and even some low- and middle-income countries in the level of vaccinations that we've been able to implement. So if you want to look it that way, we have a lot of work to do, and that's exactly what the President said.

DB: So speaking of vaccines, what's your advice? I know we have the bivalent available now. What is your advice on which vaccines to get and when that's appropriate? AF: Well, first, you've got to get your primary series. So, I mean, that's the one where I said only 67 percent of the country has gotten their primary series, which for the most part, with some exceptions, is an mRNA vaccine, either Moderna or Pfizer, given anywhere from three to four weeks apart as the primary. Then the issue is about giving people booster shots. So right now, if you're asking a clear question, of today, with the bivalent BA.4-5 boosters or updated vaccines is a better terminology to use, they are available now throughout the country. We've ordered 171 million doses. Who should get it? Anyone who is vaccinated with the primary series and has not received a shot longer than two months ago should get it. So if I got my last shot, let’s say in July -- August, September, two months later, you should get the bivalent. If you were infected three months or more ago, you should then get the updated vaccine.

Let me give you an example for clarity for the audience. I was infected in the end of June of this year, even though I had been vaccinated. Fortunately, because I was vaccinated, I had a relatively mild illness. At my age, had I not been vaccinated, the chances are I could have had a real severe outcome because elderly are more prone to get severity of disease. So if you take the end of June, take the end of July, the end of August, the end of September. I plan to get my updated BA.4-5 bivalent at the end of September, the first week in October.

DB: I think that’s a very useful advice, and actually I will be doing the same. How are you personally navigating this stage in the pandemic? What precautions are you taking, if any?

AF: Well, I certainly continue to take precautions. And I think it's important that you ask me personally that question, because people have different levels of risk of severity of disease. I am a person who is relatively healthy, but I'm at an elderly age. I'm 81 years old. I'm going to be 82 in December. So I, statistically, would have more of a risk. So the precautions I take, I stay up to date on my vaccinations, number one. And when I go to a place that's a congregate indoor setting where there are a lot of people and I don't know the status of their infection, their vaccination or what have you, I would, for the most part, wear a mask. When I'm with people who I know what their status is, people who are recently vaccinated or people who come in and test before they come in, I could have a dinner in my home or in the home of a friend without any concern. But if I go to crowded places, certainly on an airplane, even though it isn't required any more, if I go on a prolonged or even a short airplane trip, again, because of my increased risk as an elderly person, I wear a mask on the plane.

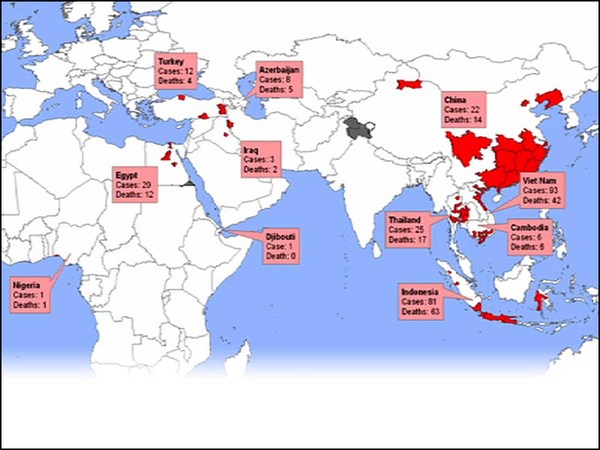

DB: So switching gears a little bit, or taking a step back, are consecutive pandemics kind of our new reality? We obviously had the monkeypox outbreak. And if that is the case, how do we cope with consecutive pandemics? AF: Well, you know, we have had, probably without the general public noticing it much, we have had, in the history of our civilization, outbreaks of emerging infections, some of which turn into pandemics. We've had them before recorded history. We've had them in the lifetime of some of us, you and I. We're going through one right now. So given the fact that most of the outbreaks of new infections come from the animal-human interface, which is sometimes intruded upon, as it were, where people, either by climate change or by intruding on forests, “uninhabited by human” places in the world, you’re going to get jumping of species. Or in markets where you put animals from the wild in contact with humans, which is exactly what happened with SARS-CoV-1 and highly likely happened with SARS-CoV-2. We will continue to get outbreaks. Pandemic flu generally comes from a situation where you have the animal species that harbor influenza, pigs, fowl, birds and humans together in that environment. That's how you get the bird flu that tend to challenge us a fair amount or the swine flu.

So the short answer to your question, David, is that we will continue to get outbreaks of new infections. The critical issue is how do you prevent them from becoming pandemics? And that's what's called pandemic preparedness, which is a combination of scientific preparedness, like we did with the rapid development of vaccines for COVID-19, which was a highly successful scientific endeavor, matched with a public health response, which we didn't do as well, in the public health response, because we had spread of infection in a way that we could have done better in controlling it.

DB: So speaking of that, this is not your first epidemic, but you've made historic contributions to the AIDS epidemic and now COVID-19. But is there anything you wish you had done differently in those cases?

AF: Well, there always is. I mean, it's a question of when you're involved -- Nobody is perfect, certainly not I or any of my colleagues. But when you're dealing with an emerging, moving, dynamic target, which by definition is what a pandemic is, particularly if it's with a pathogen that you've never had experience with, like HIV in the very early 1980s, or the COVID-19 pandemic in the first months of 2020, you could always say, if we knew then what we know now, and there was a lot of things that we didn't know, we certainly would have done things differently. And that's why you have to be humble and modest to realize if you are going to be following the science, the science which gives you data and information and evidence is going to change, particularly in the early phases of the outbreak. Did we know how easily it was spread from human to human? No. Did we know that it was aerosol spread? No. We thought in the beginning it was like influenza, mostly droplets from a sick person. Did we know that 50 to 60 percent of the transmissions were [from] someone who had no symptoms at all, which clearly impacts how you approach an outbreak? Did we realize that instead of the typical outbreak, where it goes up, it comes down and then you're done with it, we had no concept that you'd be seeing different waves and different variants that came along. So the answer to your question, if we knew all of that from the beginning, we certainly would have done things differently. But unfortunately we didn't. And you try to be flexible enough and humble enough to change and modify how you approach things based on the recent data. That’s not flip-flopping. That is truly following the evidence and following the data.

DB: Right, that's just how science works, it's constantly updating and especially in a real-time situation like this pandemic. But are there any, I don't know, specific regrets you have, something you would take back if you could?

AF: Well, it depends. Yeah, I mean, obviously in the beginning when we were under the impression, or didn't fully realize that there was aerosol spread, we were under the impression, which was true, because we were told that, that there weren’t enough masks for the health care providers. And if we started everybody hoarding masks, there wouldn't be masks available to the health care providers. We didn't realize that out of the health care setting, like the hospital setting, that masks were effective in preventing acquisition and transmission. We didn't know that. We know it now for sure, but we didn't know it then. We didn't know that the silent spread from people who were without symptoms. And that meant we didn't know that, while we were looking for sick people, there were many, many, many more people without symptoms that were in society spreading the infection in a way that was not detectable, below the radar screen. Had we known that, I absolutely would have said right from the beginning, everybody wear a mask all the time in an indoor setting. But we didn't say that then. It was only when it became obvious. So if we had known that early on, we would have told people to wear a mask.

However, I must say, David, given the reluctance of people to wear masks, even now that we know all that stuff, I'm wondering how well that would have been received if at a time when there were ten or so documented infections, if you told the country that everybody should wear a mask in an indoor setting, not so sure that would have been broadly accepted.

DB: Yeah. And this seems to be something that, the United States anyway, has been through before, with the Spanish flu and masking and then anti-mask protests. And it seems to be in our, let's say, societal immune response to these pandemics.

Flipping it a little bit, how do we make sure we're not caught so, sort of, unprepared next time?

AF: Well, you know, it's interesting, David, what you mean by unprepared, because the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health evaluated different countries' preparedness for a pandemic. And guess who was evaluated to be first in the world? The United States of America. Guess who has the most deaths per population? The United States of America. So, you know, there's preparedness, and there's response, there's execution of your preparedness plans that we did not do so well for any of a number of complicated reasons, one of which was the fact, and is, that this outbreak occurred at a time of really profound and deep divisiveness in our own country. That where we had something we hadn't seen before, where political ideology played a role in whether you did or did not accept the recommended public health countermeasures, be it wearing a mask, indoor settings, quarantining, taking a vaccine, getting a boost. If you look at the country and look at the demography of the country with regard to ideology, there should never be that red states vaccinate much less than blue states. There's no reason for that at all because public health risks and public health implementation should be uniform throughout. And we didn't see that.

DB: Yeah, let's talk about that a little bit more because obviously, you've had to cope with an incredibly polarized response to your work in which not just ordinary citizens, but even politicians have called for your resignation and various other things. How do you deal with that, how do you keep your cool? You're quite cool about this.

AF: Well, calling for your resignation is mild compared to having somebody arrested who was trying to kill you. So, I mean, there's a big spectrum of pushing back against public health people. And that's one of the really unfortunate things. I mean, I keep my cool because that's just the nature of the kind of person that I am. When you're dealing with a very, very difficult situation, you've got to keep your cool. I mean, I learned that in my early training in medicine. When you're in the middle of emergency, somebody is dying in front of you, you've got to keep your cool all the time. And that's something that's just part of my inherent training as a physician and as a person. But what we faced was well beyond that. I mean, public health officials, not only myself, I'm a very visible one, but many of my colleagues are being threatened and hassled and harassed, themselves and their families, the way my family is being harassed, merely because of saying things that are purely public health, common sense, tried and true principles of how to keep people safe. That is really extraordinary that that's going on in our country.

DB: Yeah. I'm also going to ascribe it to the Brooklyn upbringing. That gave you some cool, too.

(Laughter)

But a quick follow up, how do you, like, with all that going on, with those horrifying threats, how do you unwind from all this? How do you, you know, keep it together and give yourself some space to breathe?

AF: Well, I have an extraordinarily supportive family, my wife who's with me, my children are grown and live in different parts of the country. But they are very supportive of me with texts and calls and knowing what I'm going through. So I have three daughters, which they, you know, they try to take care of their daddy, so it really helps. But my wife is extremely supportive, and we do things together. I mean, I work a preposterous amount of hours a day, but every day I try to get some exercise in and it's usually a few mile walk with my wife, whether that's on the weekends very early in the morning, or during the week late at night when I come home. We try to get some form of exercise in to diffuse the tension, hopefully every day. And we're pretty successful at that.

AF: Well, good for you. So you're retiring after a very long and distinguished career. Congratulations. You will have successors. What lessons would you want to offer your successors based on your tenure?

AF: First of all, I’m not retiring in the classic sense. As my wife, says, David, I’m “rewiring,” not retiring, because I do intend to be very active. And that was one of the reasons why I stepped down at this point in time. Because while I still have the enthusiasm, the energy and thank goodness, the good health to be able to do something else for the next few years, I want to use the benefit of my experience of being at the NIH for almost 60 years, for being the director of the Institute for 38 years, and for having the privilege of advising seven presidents of the United States on public health issues, to use that experience to hopefully inspire by writing, reading, traveling, lecturing, inspiring the younger generation of scientists and would-be scientists to at least consider a career in public service, particularly in the arena of public health, and science and medicine.

Having said that, my advice to the person who will ultimately replace me would be to focus on the science and be consistent with the science and do not get distracted by a lot of the peripheral things, the disinformation, the misinformation, the attacks on medicine and science and public health. Focus like a laser beam on what your job is and don't get distracted by all the other noise that's out there because there is a lot more noise now than there was a few decades ago. And by noise, I mean misinformation and disinformation about science.

DB: For sure. I've definitely noticed that as the science curator. But pivoting a bit, let's talk about hope. What gives you hope about the future? Are there treatments or other things coming down the pipeline that you're excited about?

AF: Well, science is an absolutely phenomenal discipline. It's discovery. It's ... brand new knowledge. Pushing back the frontiers of knowledge that we would not have imagined we would be in. If you look at medicine and science, how it's changed in a very, very positive way from the time I stepped into medical school in 1962 to the time now of the things that are available to me as a physician and as a scientist. I have great hope that if we continue the investments in basic and applied science, that we will be able to accomplish things in the arena of health, individual health, and public health and global health that were really unimaginable just decades ago. So I have a great deal of optimism about what the future holds for science and medicine.

And that's the reason why one of the things I'm going to try and do in my rewired post-government life is to encourage young individuals to consider a career in medicine, science and public health, because the opportunities are really limitless. We are at a stage now the likes of which people who antidated us never would have imagined the opportunities in science that we have. So I'm very optimistic about where we're going.

DB: Me, too. But you mentioned earlier how climate change is affecting pandemics. What worries you about the future that we're facing?

AF: Well, just some of the things that you mentioned. We do have a growing element of anti-science in society. Disturbingly, growing in the United States. And when I talk to my colleagues internationally, depending upon the country that they live in to a greater or lesser degree, there's some element of that. The thing that bothers me is a denial of science and what science is showing us. A denial of the issues of climate and the environment, a denial of scientific principles and conspiracy theories about things that push people away. I mean, some of them are laughable, but you would be astounded, David, at the number of people who believe it. That the vaccines were made by Bill Gates and I and we put a chip in it so that we could follow people around and know what they're doing and get into their head. The idea that there's a conspiracy, that we’re making billions of dollars on vaccines, and that's why people are promoting vaccines, so that people like me and others who are public figures ... I mean, based on no data. But once it gets into the social media, it explodes and conspiracy theories explode. Even though all of the evidence proves it wrong, proving something wrong today doesn't seem to matter much. That's really strange and weird, isn't it, David?

DB: Yeah, yeah. Well, it's, I think, an old phenomenon. There's a famous saying that I'm going to mangle about by the time the truth gets out of the barn, the lie is halfway around the world. And that's definitely the world we're living in.

I do know you have to go and, you know, finish out your tenure and then get ready for your rewiring, which I'm excited about. I'm excited to see what's next. But do you have a last bit of advice for the public? One thing you hope everyone takes away from your time as director and your time in public health?

AF: Yeah, David, there are so many things, but I think one thing that stands out, particularly in the climate and the environment that we're in right now, is that people need to get involved in a proactive way in spreading the truth about what scientific principles are and what they mean and how they can be of great benefit to society and to try and make our population more science literate than it is right now by talking about things. The truth, you know, the easiest way to counter misinformation and disinformation is to be enthusiastic about spreading correct information. A little bit about the metaphor that you said about the truth and lies. Be spreaders of facts and truth. Everybody's got to be a contributor to that. And that's one of the things I think we can do better.

DB: Yeah, I would agree. And we're definitely trying here at TED. Well, Dr. Fauci, I know our members are incredibly thankful, I personally am incredibly thankful. So thank you so much for your work and for joining us today.

AF: My pleasure, David, thank you so much for having me.

[Want to join conversations like this live?]

[Become a TED Member!]

[Sign up at ted.com/membership]