From the 1650s through the late 1800s, European colonists descended on South Africa. First, Dutch and later British forces sought to claim the region for themselves, with their struggle becoming even more aggressive after discovering the area’s abundant natural resources. In their ruthless scramble, both colonial powers violently removed numerous Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands.

Yet despite these conflicts, the colonizers often claimed they were settling in empty land devoid of local people. These reports were corroborated in letters and travelogues by various administrators, soldiers, and missionaries. Maps were drawn reflecting these claims, and prominent British historians supported this narrative. Publications codifying the so-called Empty Land Theory had three central arguments. First, most of the land being settled by Europeans had no established communities or agricultural infrastructure. Second, any African communities that were in those regions had actually entered the area at the same time as Europeans, so they didn’t have an ancestral claim to the land. And third, since these African communities had probably stolen the land from earlier, no-longer-present Indigenous people, the Europeans were within their rights to displace these African settlers.

The problem is that all three of these arguments were completely false. Almost none of this land was empty and Africans had lived here for millennia. Indigenous South Africans simply had a different practice of land ownership from the Dutch and British. Land belonged to families or groups, not individuals. And even that ownership was more focused on the land’s agricultural products than the land itself. Community leaders would distribute seasonal land rights, allowing various nomadic groups to graze cattle or forage for vegetation. Even the groups that did live in large agricultural settlements didn’t believe they owned the land as private property. But the colonizing Europeans had no respect for this system of ownership. They concluded the land belonged to no one and could therefore be divided amongst themselves.

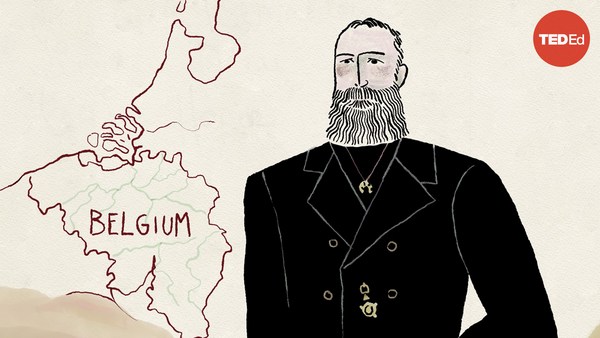

In this context, claims that the land was “empty” were an ignorant oversimplification of a much more complex reality. But the Empty Land Theory allowed British academics to rewrite history and minimize native populations. In 1894, the European parliament in Cape Town took this exploitation even further by passing the Glen Grey Act. This decree made it functionally impossible for native Africans to own land, shattering the system of collective tribal ownership and creating a class of landless people. To justify the theft, Europeans painted the locals as barbarians who lacked the capacity for reason and were better off being ruled by the colonizers.

This strategy of stripping locals of their right to ancestral lands and casting native people as savages has been employed by many colonizers. Now known as the Empty Land Myth, this is a well-established technique in the colonial playbook, and its impact can be found in the history of many countries, including Australia, Canada, and the United States. And in South Africa, the influence of this narrative can be traced directly to a brutal campaign of institutionalized racism.

Barred from their lands, the once self-sufficient population struggled as migrant laborers and miners on European-owned property. The law forbade them from working certain skilled jobs, and forced Africans to live in racially segregated areas. Over time, these racist policies intensified, mandating separation in urban areas, restricting voting rights, and eventually building to apartheid. Under this system, African people had no voting rights, and the education of native Africans was overhauled to emphasize their legal and social subservience to white settlers. This state of legally enforced racism persisted through the early 1990s, and throughout this period, colonists frequently invoked the Empty Land Theory to justify the unequal distribution of land.

South African resistance movements fought throughout the 20th century to gain political and economic freedom. And since the 1980s, South African scholars have been using archaeological evidence to correct the historical record. Today, South African schools are finally teaching the region's true history. But the legacy of the Empty Land Myth still persists as one of the most harmful stories ever told.