Thirty years ago, I walked into a nursing home, and my life changed forever. I was there to visit my grandmother Alice. She was a very powerful woman who had lost a battle with a stroke that stole her ability to speak. Alice had just three forms of communication left. She had this sound that was like, "tss, tss, tss," that she could shift in tone from emphatic, "no, no, no," to enticing, "yes, you've almost got it." She had an incredibly expressive index finger, which she could shake and point with frustration. And she had these enormous pale blue eyes that she could open and close for emphasis. Wide open seemed to say, "Yes, you've almost got it," and closing slowly was -- well, it didn't really need much translation.

It turns out that Alice had taught me that everyone has a story. Everyone has a story. The challenge for the listener is how to invite it into being, and how to really hear it.

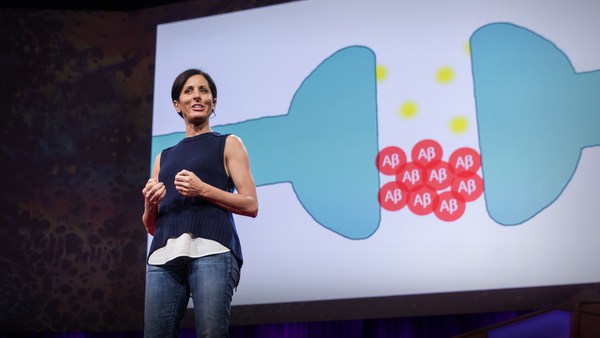

Now, Alzheimer's and dementia, these are two words that, when you say them in front of people, you can watch a cloud descend over them. You can imagine me at dinner parties. "What do you do?" "Well, I invite people with Alzheimer's and dementia into expression. Where are you going?"

(Laughter)

Fear and stigma wrap themselves so tightly around an experience that affects 47 million people across the world, and they can live with this diagnosis for between 10 and 15 years, and that number, 47 million, is supposed to triple by 2050. Family and friends can fade away, because they don't know how to be in your company, they don't know what to say, and suddenly, when you need other people the most, you can find yourself really painfully alone, unsure of the meaning and the value of your own life.

Science is pushing for treatments, dreaming of cures, but loosening that grip of stigma and fear could ease the pain of so many people right now. And luckily, meaningful connection doesn't take a pill. It takes reaching out. It takes listening. And it takes a dose of wonder.

That really has become my unending quest, set in motion by Alice and then later on by really countless elders in nursing homes and day centers and those struggling to stay at home. And it comes down to the question of how. How do you meaningfully connect?

I got a big part of that answer from a long-married couple in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where I'm from, Fran and Jim, whom I met on a rather dreary winter day in their tiny, little kitchen in a humble duplex over by Lake Michigan. And when I walked in, Fran and a caregiver and a care manager greeted me really warmly, and Jim stood staring straight ahead, silent. He was on a long, slow journey into dementia and was now beyond words. I was there as part of a project team. We were doing what we called "artistic house calls," with a really simple goal of inviting Jim into creative expression, and hopeful in modeling for Fran and the caregivers how they could meaningfully connect using imagination and wonder. Now, this was going to be no small task, because it turns out Jim had not spoken in months. Could he even respond if I invited him into expression? I didn't know.

Family members, when they try to connect, most commonly will invoke a shared past. We say things like, "Do you remember that time?" But nine times out of 10, the pathway for that one answer to travel in the brain is broken, and we're left alone with a loved one in the fog.

But there is another way in. I call them beautiful questions. A beautiful question is one that opens a shared path of discovery. With no right or wrong answer, a beautiful question helps us shift away from the expectation of memory into the freedom of imagination, a thousand possible responses for people with cognitive challenges.

Now, back in the kitchen, I did know one thing about Jim. I knew that he liked to walk along Lake Michigan, and when I looked around that kitchen, I saw, over by the stove, this trunk that was just covered in little pieces of driftwood. And I thought, "I'll try a question that he could answer without words." So I tried, "Jim, can you show me how water moves?" It was silent for a while, but then really slowly he took a step over to that trunk and he picked up a piece of the driftwood and he held it out, and then very slowly he began to move his arm, leading with that driftwood. In his hand, it became buoyant, in sync with the motion of the waves that he made with his arms. It began this slow journey across calm waters, this gentle rolling to the shore. Transferring his weight from left to right and back again, Jim became the waves. His grace and his strength just took our breath away. For 20 minutes, he animated one piece of driftwood after the other. Suddenly, he was not disabled. We were not gathered in this kitchen for a care crisis. Jim was a master puppeteer, an artist, a dancer.

Fran later told me that that moment had been a turning point for her, that she learned how to connect with him even as he progressed through the dementia. And it really became a turning point for me, too. I learned that this creative, open-ended approach could help families shift, expand their understanding of dementia as more than just tragic emptiness and loss into also meaningful connection and hope and love. Because, creative expression in any form is generative. It helps make beauty and meaning and value where there might have been absolutely nothing before. If we can infuse that creativity into care, caregivers can invite a partner into meaning-making, and in that moment, care, which is so often associated with loss, can become generative.

But so many settings of care offer bingo and balloon toss. Activities are passive and entertainment-oriented. Elders sit and watch and applaud, really just distracted until the next meal. Loved ones trying to keep their partners at home sometimes don't have anything to do, and so they resort to watching television alone, which compounds the symptoms of dementia with what researchers now tell us really are the devastating impacts of social isolation and loneliness.

But what if meaning-making could be accessible to elders and their care partners wherever they lived? I've really been totally transformed and captivated by bringing these creative tools to caregivers and watching that spark of joy and connection, discovering that creative play can remind them of why they do what they do.

Bringing this creative care to scale could truly shift the field. But could we do it? Could we infuse it into a whole care organization or an entire care system?

The first step towards that goal for me was to assemble a giant team of artists and elders and caregivers in one care facility in Milwaukee. Together, over two years, we tackled reimagining the story of Homer's "Odyssey." We explored themes. We wrote poems. Together, we created a mile-long weaving. We choreographed original dances. We even explored and learned Ancient Greek with the help of a classics scholar. Hundreds of creative workshops we embedded into the daily activities calendar and invited the family members to join right along with us, and had caregivers and staff from every single area of care collaborating on programming for the first time. The culminating moment was an original, professionally produced play that blended the professional performers right alongside the elders and the caregivers, and we invited a paying audience to follow us from scene to scene, one in the nursing home, in the assisted living dining room, and finally in the chapel for the final scene where a chorus of elders all playing Penelope lovingly welcomed Odysseus and the audience home. Together, we had dared to make something beautiful, to invite elders, some with dementia, some on hospice, into making meaning over time, to learn and grow as artists. All this in a place where people were dying every day.

I find myself now in a place where I'm having to tackle this challenge of meeting a person with dementia across that gap in a more personal way. At a family dinner over the holidays, my mother, who was seated next to me, turned to me and said, "Where's Annie?" My funny and beautiful and feisty mother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's. And I found myself in that place that everyone dreads. She didn't recognize me. And I had to figure out fast if I could do what I'd been coaching thousands of other people to do, to connect across that gap. "Do you mean Ellen?" I said, because my sister's empty chair was just right across the table from us. "She just went to the bathroom." And my mother looked at me, and then something deep inside sparked, and she reached out and smiled and touched my shoulder and she said, "You're right there." And I said, "Yes, I am right here."

I know that that moment is going to happen again and again, not just for me and my mom but for all 47 million people across the world and the hundreds of millions more who love them.

How will we answer this challenge that is going to touch the lives of every family? How are our care systems going to answer that challenge? I hope it is with a beautiful question, one that invites us to find each other and connect. I hope our answer is that we value care and that care can be generative and beautiful. And that care can put us in touch with the deepest parts of our humanity, our yearning to connect and make meaning together all the way to the end.

Thank you.

(Applause)