I'm here to tell you about some of the most vital heroes of our time. They fight a hidden war across our world that will define our future. They battle on behalf of us all to protect mountains, rivers, forests and the last pristine ecosystems. Yet these warriors pass almost invisible. We don't know their names, and we rarely read about them.

These obscure heroes are environmental defenders. They mount protests and fight legal and armed battles, and have already saved many plants and animals from destruction. Small Indigenous communities make up only five percent of the world's population, but they defend 80 percent of all the biodiversity that remains on Earth. Their stories aren't told, in part because many of them live in war zones.

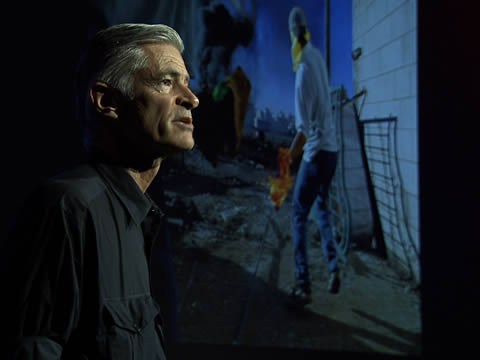

I've committed myself to reporting on forgotten conflicts like those in the Congo and the Central African Republic. For several years now, I’ve documented the war for the environment and I'd like to show you this fight for the future from the inside.

The front line of this war runs right through Latin America. At least 1,700 environmental defenders have been killed over the last decade. Nearly 70 percent of these assassinations were perpetrated on the land between Mexico and Argentina. Three years ago, I read that more than 50 defenders were murdered in Mexico just that year, making it the world's deadliest country for the defense of nature. I didn't know how long it would take to investigate these crimes against environmental defenders, so I bought a one-way ticket there to uncover and tell the stories of their sacrifices.

One of the first defenders I met was David Salazar. I met him on the Pan-American Highway. His community had hijacked buses and trucks and blockaded the longest highway in the world to protest a planned industrial mega-project.

Their lowland forest, called El Pitayal, had been marked for destruction to build a new factory complex. They're up against the US and Mexican governments and multinational companies that want this vast inter-oceanic mega-project to go forward. According to researchers, Mexico's violent cartels also see a chance to boost their multi-billion dollar revenues through theft and protection rackets on their territory. Governments, companies and cartels stand to profit.

When David's protests didn't stop the construction, saboteurs burned government vehicles near their forest. Their weapon was fire, which locals call "lumbre." We don't know who burned the vehicles, but the community authority, David, was singled out. The other men and women organizing the resistance warned me: David's going to be attacked or even assassinated. The municipal police had once severely beaten him up.

That afternoon, I sat down with David in his yard and I pulled out my notebook. "Aren't you afraid they'll kill you?" I asked. He said, "Of course I'm afraid." David wasn't killed, but two months ago, a Mexican court sentenced him to 46.5 years in prison for damaging property, effectively handing him a life sentence. But David told me all the world’s prisons aren’t large enough to fit the defenders willing to risk everything to protect the Earth. I've gotten his community legal assistance.

Since the courts don't reliably protect the planet, other communities have armed themselves. On Mexico's Pacific coast, a locality of only a thousand people fights a drone war to protect their ancestral mountain. A European company has built a huge iron mine nearby, and now wants to expand its excavation to this pristine mountain called La Mancira. A ferocious cartel regularly strikes the community using drones, as it disappears and kills anti-mining activists.

The European company denies allegations made by local activists that it's involved in any illegal activity. But the mountain is full of gold. It is also a home to jaguars, rare plants and an intact forest.

This isolated Indigenous community, called Santa Maria de Ostula, fights back to defend nature and to defend its culture and its people. It sends its young men to the front lines. It scavenges weapons after its victories over the cartels. I'm told it's common knowledge that factions of the Mexican army and police sell weapons to the cartels and communities, thereby profiting from both sides of this war.

The cartels, by some estimates, Mexico's fifth largest employer, recruit young, poor men, arm them, and have them run illegal businesses in remote places that are dangerous for journalists. Scores of reporters have been killed in Mexico, many of whom investigated illegality and corruption. I carry cigarettes and chocolate to hand out, so any cartel fighters I run into might spare me.

I asked one of Ostula's young defenders, a councilman named Pedro, to take me to their front line. I'm not showing you his face for his protection. He said, "I'll take you to the European iron mine, but it's crawling with cartel fighters." Ostula had just lost three defenders in a cartel ambush and was braced for a new attack.

Millions of dollars are extracted each year from the iron mine. But in the nearby municipal capital, the houses were dirty. Paint peeled, the walls crumbled. We drove into a compound with an ordinary low building. I wasn't allowed, of course, to take photos inside, but this is what I saw. As I walked in, it was like a fixer upper meets the movie "The Matrix." I was surrounded by 50-millimeter guns and assault rifles covering the walls. Large drones, walkie-talkies. Bullets lay on the ground. A carpenter repaired the roof, fortified with three layers.

I interviewed the base commander, a hefty man named El Chopo. I asked where the cartel attacked. "Here," he said. I looked out into the valley and asked how often they attacked. Every two days. “They sent four drones this morning,” he said. "Carrying C4 explosives mounted on motor heads. They didn't drop those bombs, but they'll be back later today." A fighter jumped out of his hammock and loaded his rifle. “Estamos listos.” “We’re ready.”

This is how the battle to save nature is waged. One mountain, forest and river at a time.

The roads were quiet as I drove with Pedro, the councilman, to the European iron mine. It was a wide, gray mountainside. Mexicans say the mining companies work to “licuar las montañas,” or “blend the mountains down.” Pedro pointed up at an old shack. He said, “The cartel fighters are behind those walls and we should leave, because I’m on their hit list.”

These remote wars for the environment can seem to not exist. Meanwhile, the international mining companies are winning so-called corporate sustainability awards.

That night, walking on Ostula’s beach, I waited for turtles to swim ashore to nest. I saw their soft white egg shells glow in the moonlight. In the morning, baby turtles hatched. The turtles seemed oblivious to the humans fighting around them. Or maybe they knew about the environmental defenders.

I've now covered a dozen battles for pristine ecosystems rich in titanium, copper, gold, water, sand, forests, jaguars, butterflies. Without war reporters on the ecological front lines, environmental defenders are killed in obscurity, ecosystems are destroyed in silence and the perpetrators get away.

In my own work, I've shone a light on war crimes in Central Africa. I've seen criminals be prosecuted. Yet we won't win the global environmental war unless we pay more attention and join forces with brave defenders around the world. These small bands of fighters are fearless. They fought colonial conquerors hundreds of years ago, then led fiery revolutions and remarkably, hold off heavily armed cartels.

Together with them, you and I now need to take on our biggest and most important war. To save all that remains of nature and ensure our survival.

Thank you.

(Applause)