Femi Oke: I have a theory that Africans have this hotline to joy.

Angélique Kidjo: Oh yeah.

FO: We greet each other, we welcome each other. There's, within us as a continent, there is great joy.

AK: Absolutely. It's a state of mind for us. It's either laugh or die. We don't have the choice. And that's where the proverbs come from, that's where all those mimic, sometime -- can be an insult, or going, "Get out of here. You're making a fool of yourself." Our body, we have signs. And we look at each other and the situation ... it might be a dire situation, and then we start laughing and go, "Somebody make a huge mistake. And you are in a ditch, You can't even get yourself out." And we laugh and we're happy at the same time. That's why I say it's a state of mind.

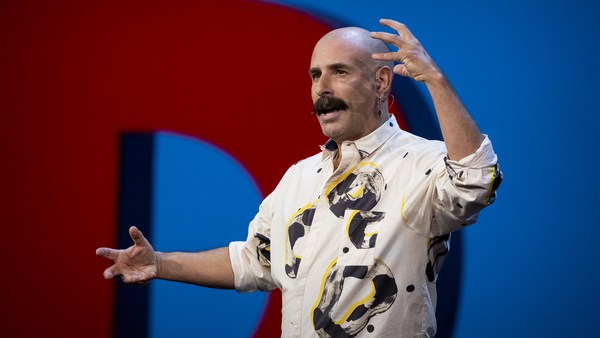

FO: I have seen people watch you perform, and they’re in the audience, they are mesmerized, they are smiling, they are joyful. Do you have an awareness of what you are doing to your audience?

AK: No, I don't have any awareness because for me, every concert is a start over. I never take any public for granted because you never know what the concert is going to be. You can have plan in your head, you can have your set list and everything. It’s just to help you, it’s just like, a parameter that you put in there to be able to perform. But what happens after that is out of your hands. That's the power of music. When I'm holding my microphone, for me, stage is my sanctuary.

FO: I was looking up some of the comments people write when they watched you online on YouTube. Now, normally I wouldn't do this, but this is fine. This is not scary. "Pure love for Mama Angelique. A beautiful ball of energy."

AK: (Laughs)

FO: You know what you're doing.

AK: Well, being on stage for me is the most important thing. I hate to be in studio, but I've had to learn throughout the years that I need to be in the studio to be able to perform, to be on stage. And that energy that we're talking about, the public give it to me. I can't keep it. If I keep it, I will explode. I mean, just face it. And I can't sleep, like, when I finish a concert, it takes me like four hours for me to dwindle down and to be able to sleep. It’s terrible, because I’m wired up. I don't need no drugs, I don't drink coffee. I don't drink alcohol, I don't take anything, I don't need it. The music is my drug. So therefore, when I'm onstage, I'm just trying to convey the happiness, the joy and the strength that we have as human beings to prevail in every circumstance. Because music has shown me, when I'm facing the public, I see people from around the world, all different skin tones and probably all people that speak different languages, that makes you humble.

FO: And you've gone so beyond what would be expected of somebody with your profile as a musician. You are not just a musician, you're not just an artist. You are also an educator.

AK: Education is everything. And when I started this journey with my foundation Batonga, one thing I have in mind is what my father always used to say. An educated person is a peacemaker. And it's true, because when you are educated and understand the connectivity, everything in the world we live in is connected, even us. And if there's one thing we learned during the pandemic, it's that we cannot live alone. Lockdown or not, it becomes a point where we need others to be able to celebrate our own humanity.

From the moment I started going to school, it triggered something in me. Not only the curiosity, but I was thirsty of learning. What can I learn every day? And I would come home and I ask questions. And I'm lucky enough to have 10 brothers and sisters that come before. Some of them have been there. So if I ask questions, somebody's always going to answer me. And then I get to high school and I start seeing a different side of education. Because when I finished primary school, most of my girlfriends, we made plan. When we get to high school, we're going to do this and that. Some of them disappeared from the radar. And I’d be asking the question: “Why aren’t they here?” Then, my girlfriend in the same street where I grew up, right across my house, never make it to high -- And I'm like, "Dad, what is going on?" And then he went and found out that she got married. And I was -- It was a day that I'm like, "Is it worth living, if at that age you're going to marry somebody without me knowing what was going on?" So to start my foundation, secondary school, is to allow those young girls to buy time. To have a future, to decide the future they want to have instead of being married young and end up dying on a delivering bed. So for me, education not only allowed us to understand the complexity of this world, it also unleashed the power that we have to understand when we stand in front of injustice, our rights, what is right and what is wrong. And when it comes to women, especially in the continent of Africa, I start realizing that the vision of my father for women is totally different from the vision of the father of my friends. Because when I go to their home, I couldn't speak because it was not allowed. You have to be given permission to speak. While in my house, you have something in your mind, go right ahead. Somebody's going to answer you. And I start seeing the differences, and I said, “How can we break this cycle of always women have to be the ones that get quiet and men speak up even when they say nonsense.

FO: The Batonga Foundation, it creates opportunities for women and girls. It creates a future for them. It sounds easy, though, to say that: creates opportunities for women and girls, easy. But it's not. Can you give us an example of your advocacy work that has been difficult but you've worked through it and you've seen success and happiness the other side?

AK: The hardest thing ... when I started was not being able to get the girl to speak. It was breaking my heart. "What is your name?" There's no answer, they look at you like. And I’m like, “Why? Why? Tell me what you need. I'm here to help. I'm not going to tell you what to do."

From the day they realize and have confidence that I'm not here to judge their choices, some of them were already mothers. And you have a lot of pride when you're talking to underprivileged people. Because I decided from the get-go to walk the dirt road where no one wants to go because that's where you have fewer opportunities. And I was not going to let those girls be marginalized and left in limbo. So from the moment they start speaking, to me, is the moment I start seeing how we can move forward together.

So we start doing, as an organization, we needed data, right? Because I've done it ten years, sending people to high school, they end up in university, all that kind of stuff. But I wanted to understand why and the reason of the drop out of the girls. So through that, we find out many different reasons. One of the reasons of the drop out is that in primary school, the teachers were not good enough, so they didn’t have the tools to succeed in secondary school. And there's so much ammunition you can go through when you appear to be a stupid person and you're not stupid, you just don't have the tools. Then you drop out. Pregnancy, of course, and family poverty. And one thing that came out of that data collection is all of the girls say, “We need a safe space. We need a place where we can talk to one another and we can work together and support one another." I said, "It's done." So we start creating the girl club and built a curriculum based on their need. And they ask to be taught how to prevent rape. How can they run away? How can they do things? So we come up with simple thing. Don't go out when it's getting dark. When you're walking and you have a shadow behind you and you feel uncomfortable, don't start, don't try to be courageous. Don't try to be daring. Run away. And we prepared the village. If a girl comes to your house, keep her there until the family member can come because there's a danger in the street. So we start the whole thing like that.

What is going on today that I’m really proud of is that those young girls are becoming entrepreneurs and creating jobs. They are in total control of what they do with their money. They decided they're going to save money. It's not me. For the children not to go through this again. What they want is to break the cycle of poverty. The next step that I'm taking is to go to the northern part of my country, Benin. The girls in Benin, at eight years old, are sent to the man that's going to marry them home, they become maids, until they have -- And I want to break that cycle. I've been working hard. I’ve been asking for help with this for so long. We're going to start there with local organizations. We don't bring anybody from outside. We work with the people that know the needs. We work with the village, the head of the villages, the mothers. We want people to see for themselves the progress we are making and for them, to allow them to listen to the kids that they never do.

FO: What is the difference between the pleasure you get from changing a generation's life to the pleasure of being on stage at a major event, performing, and the crowd is going wild? What's the difference between that kind of joy?

AK: They are two totally different joys. The joy of seeing these girls being articulate today, talking truth to power to the head of villages telling them, "No one is touching us anymore. No one have the right to touch my boob, no." And they're adamant. I mean, the joy at taking that is that finally, you can speak up with no danger. With no fear. I mean, empowering people to that point makes me more humble. I don't even know, sometimes I'm like, "Where is the hole that I can drive in and then disappear, and let them be." But they won't let me go. They say, "We want you to come and see us, and then we learn from you." But I learn more from those girls than I can ever learn from anybody. The joy of being onstage is different, it's planting seeds worldwide for people to see their capacity, what they are capable of. How many times after concert people will come to me and say, "Angelique, how can we help?" And I'm like, "How can you help? Come on. Your neighbors. Start looking at them. You can volunteer your time for homework, there's so much you can do in your own country. Don't think that Africa is just the country where we need help. We don't need help. We need collaboration."

FO: Did you warm up your voice today?

AK: Yes, I did.

FO: What do you sing to yourself to cheer yourself up? What do you sing and is like, "Oh, that was better than Prozac."

AK: (Singing)

(Laughs)

We can sit here for days.

FO: So glad you warmed up.

When you see your Grammys lined up, and they're all shiny and extraordinary, I'm not even going to name how many, because every time I do, you get more and then this chat will date, so the many, multiple Grammys that you have won, when you look at them, Do you, "Whoo!"

(Laughs)

Does it feel good?

AK: It feels good. And at the same time, as I said before, it is a responsibility. I mean, my work, I've been nominated first time at the Grammys, it was in 1993, '94. And the first Grammy I won was 2007. And I said to people, don't take Grammy for granted. It's not about how many likes you have, it's what you have to say. What you are bringing to the table. How you are impacting the world and how you are changing the music business as it is. And for me, that responsibility is always at the core of everything I do. When I'm setting myself to write new songs, I don't think about Grammys. All I think about, how this song would help people. What impact is it going to have?

FO: I know you plan. I know you have ideas about what you want to do next. For many artists, it would be, you know, how do you want to spend your sunset years? But you have extraordinary longevity in your family. So you have another half a lifetime still to go.

(Laughter)

We are going to be going to 100-year-old Angélique Kidjo concert. And you're still going to be, "Let's go."

AK: Yeah, I'll be running around.

FO: So it feels kind of weird to talk about legacy. But what do you want people who follow your work, admire your work, see joy in your work, what do you want them to take away from it?

AK: Well, what I want people to take away from my work is their own worth, people's worth. We have too many people that think that they are worth nothing. And that hurts me. And when you give birth to a child, when a human being is coming out of your body, everything changes. Priorities, what matters, you learn to go to the core of things.

What I want people to remember is that you can fall beneath the Earth. But you always can rise. Does not matter how hard it is. Get up, and live your life. You know it, and that's how we roll.

FO: I love you.

AK: Me too.

Since the first time I met, it was a love story.

(Laughter)