When ultraviolet sunlight hits our skin, it affects each of us a little differently. Depending on skin color, it will take only minutes of exposure to turn one person beetroot-pink, while another requires hours to experience the slightest change. So what's to account for that difference and how did our skin come to take on so many different hues to begin with?

Whatever the color, our skin tells an epic tale of human intrepidness and adaptability, revealing its variance to be a function of biology. It all centers around melanin, the pigment that gives skin and hair its color. This ingredient comes from skin cells called melanocytes and takes two basic forms. There's eumelanin, which gives rise to a range of brown skin tones, as well as black, brown, and blond hair, and pheomelanin, which causes the reddish browns of freckles and red hair. But humans weren't always like this. Our varying skin tones were formed by an evolutionary process driven by the Sun. In began some 50,000 years ago when our ancestors migrated north from Africa and into Europe and Asia.

These ancient humans lived between the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, a region saturated by the Sun's UV-carrying rays. When skin is exposed to UV for long periods of time, the UV light damages the DNA within our cells, and skin starts to burn. If that damage is severe enough, the cells mutations can lead to melanoma, a deadly cancer that forms in the skin's melanocytes.

Sunscreen as we know it today didn't exist 50,000 years ago. So how did our ancestors cope with this onslaught of UV? The key to survival lay in their own personal sunscreen manufactured beneath the skin: melanin.

The type and amount of melanin in your skin determines whether you'll be more or less protected from the sun. This comes down to the skin's response as sunlight strikes it. When it's exposed to UV light, that triggers special light-sensitive receptors called rhodopsin, which stimulate the production of melanin to shield cells from damage. For light-skin people, that extra melanin darkens their skin and produces a tan.

Over the course of generations, humans living at the Sun-saturated latitudes in Africa adapted to have a higher melanin production threshold and more eumelanin, giving skin a darker tone. This built-in sun shield helped protect them from melanoma, likely making them evolutionarily fitter and capable of passing this useful trait on to new generations.

But soon, some of our Sun-adapted ancestors migrated northward out of the tropical zone, spreading far and wide across the Earth. The further north they traveled, the less direct sunshine they saw. This was a problem because although UV light can damage skin, it also has an important parallel benefit. UV helps our bodies produce vitamin D, an ingredient that strengthens bones and lets us absorb vital minerals, like calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphate, and zinc. Without it, humans experience serious fatigue and weakened bones that can cause a condition known as rickets.

For humans whose dark skin effectively blocked whatever sunlight there was, vitamin D deficiency would have posed a serious threat in the north. But some of them happened to produce less melanin. They were exposed to small enough amounts of light that melanoma was less likely, and their lighter skin better absorbed the UV light. So they benefited from vitamin D, developed strong bones, and survived well enough to produce healthy offspring. Over many generations of selection, skin color in those regions gradually lightened.

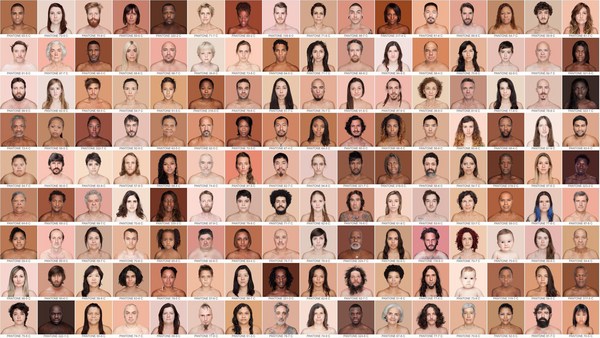

As a result of our ancestor's adaptability, today the planet is full of people with a vast palette of skin colors, typically, darker eumelanin-rich skin in the hot, sunny band around the Equator, and increasingly lighter pheomelanin-rich skin shades fanning outwards as the sunshine dwindles.

Therefore, skin color is little more than an adaptive trait for living on a rock that orbits the Sun. It may absorb light, but it certainly does not reflect character.