Consider this unfortunately familiar scenario. Several months ago a highly infectious, sometimes deadly respiratory virus infected humans for the first time. It then proliferated faster than public health measures could contain it. Now the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared a pandemic, meaning that it’s spreading worldwide. The death toll is starting to rise and everyone is asking the same question: when will the pandemic end?

The WHO will likely declare the pandemic over once the infection is mostly contained and rates of transmission drop significantly throughout the world.

But exactly when that happens depends on what global governments choose to do next. They have three main options: Race through it, Delay and Vaccinate, or Coordinate and Crush. One is widely considered best, and it may not be the one you think.

In the first, governments and communities do nothing to halt the spread and instead allow people to be exposed as quickly as possible. Without time to study the virus, doctors know little about how to save their patients, and hospitals reach peak capacity almost immediately. Somewhere in the range of millions to hundreds of millions of people die, either from the virus or the collapse of health care systems. Soon the majority of people have been infected and either perished or survived by building up their immune responses. Around this point herd immunity kicks in, where the virus can no longer find new hosts. So the pandemic fizzles out a short time after it began.

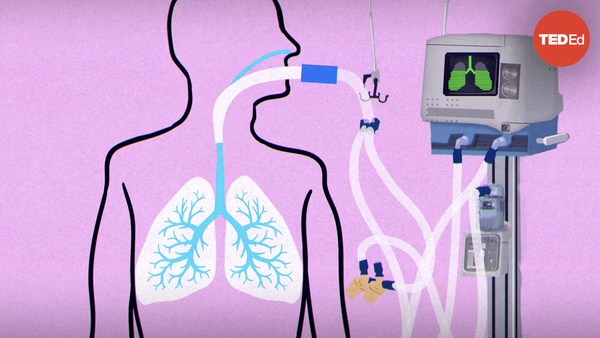

But there’s another way to create herd immunity without such a high cost of life. Let’s reset the clock to the moment the WHO declared the pandemic. This time, governments and communities around the world slow the spread of the virus to give research facilities time to produce a vaccine. They buy this crucial time through tactics that may include widespread testing to identify carriers, quarantining the infected and people they’ve interacted with, and physical distancing.

Even with these measures in place, the virus slowly spreads, causing up to hundreds of thousands of deaths. Some cities get the outbreak under control and go back to business as usual, only to have a resurgence and return to physical distancing when a new case passes through. Within the next several years, one or possibly several vaccines become widely, and hopefully freely, available thanks to a worldwide effort. Once 40-90% of the population has received it— the precise amount varying based on the virus— herd immunity kicks in, and the pandemic fizzles out.

Let’s rewind the clock one more time, to consider the final strategy: Coordinate and Crush. The idea here is to simultaneously starve the virus, everywhere, through a combination of quarantine, social distancing, and restricting travel. The critical factor is to synchronize responses. In a typical pandemic, when one country is peaking, another may be getting its first cases. Instead of every leader responding to what’s happening in their jurisdiction, here everyone must treat the world as the giant interconnected system it is. If coordinated properly, this could end a pandemic in just a few months, with low loss of life. But unless the virus is completely eradicated— which is highly unlikely— there will be risks of it escalating to pandemic levels once again. And factors like animals carrying and transmitting the virus might undermine our best efforts altogether.

So which strategy is best for this deadly, infectious respiratory virus? Racing through it is a quick fix, but would be a global catastrophe, and may not work at all if people can be reinfected. Crushing the virus through Coordination alone is also enticing for its speed, but only reliable with true and nearly impossible global cooperation. That’s why vaccination, assisted by as much global coordination as possible, is generally considered to be the winner; it’s the slow, steady, and proven option in the race. Even if the pandemic officially ends before a vaccine is ready, the virus may reappear seasonally, so vaccines will continue to protect people. And although it may take years to create, disruptions to most people’s lives won’t necessarily last the full duration. Breakthroughs in treatment and prevention of symptoms can make viruses much less dangerous, and therefore require less extreme containment measures.

Take heart: the pandemic will end. Its legacy will be long-lasting, but not all bad; the breakthroughs, social services, and systems we develop can be used to the betterment of everyone. And if we take inspiration from the successes and lessons from the failures, we can keep the next potential pandemic so contained that our children’s children won’t even know its name.